A Magnum ice cream wrapper caught in the wind, a Coca Cola bottle lost at sea. When we picture plastic pollution, it’s the littering of items like these that springs to mind. But new research points to problems upstream too, tracking plastic production to the oil fields where it originates.

For the first time, fracking operations in the US have been linked to ethane exports to Europe through major petrochemical companies and on to globally recognised brands.

More specifically, these petrochemicals come from fracking in the Permian Basin in Texas. It has been described as a ‘carbon bomb’ for the catastrophic impact its full extraction would have on global emissions. Water pollution here is so bad that some residents have filmed themselves setting tap water on fire.

“It’s really about walking the talk,” says Delphine Levi Alvares, global petrochemicals campaign manager at the Center for International Environment Law (CIEL), which has released the new research in collaboration with Stand.earth.

“If we’ve rejected fracking in Europe, for the impact on our communities, why should we accept consumer products coming from fracking that has impacts on other communities?”

The data “connects the dots” that campaigners long suspected were there, Levi Alvares tells Euronews Green. Most surprising, she says, is just how concentrated the supply chain is at the start, with petrochemical giant INEOS playing a particularly pivotal role in Europe.

How do fracking-derived petrochemicals end up in European plastic packaging?

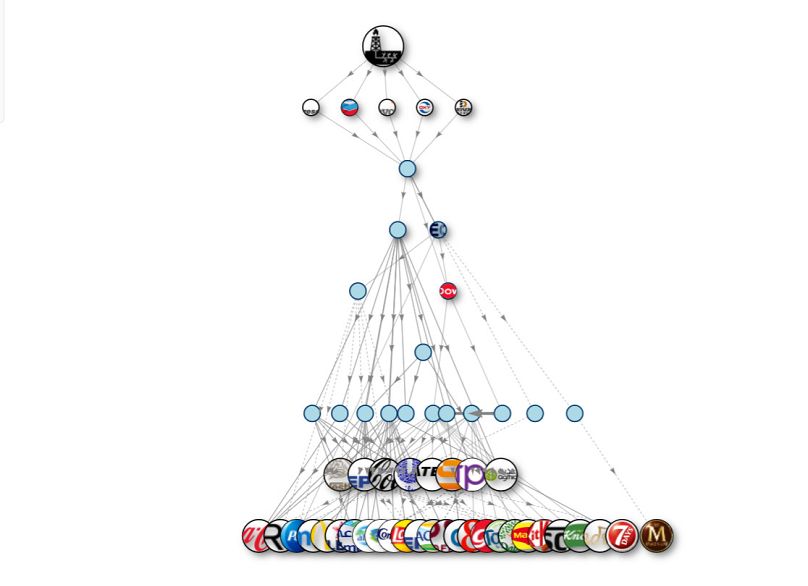

The researchers started at the source, explains Dr. Devyani Singh, an investigative researcher at Stand.earth. They identified companies with the highest yield of natural gas liquids (NGL), which include ethane, and honed in on five firms: EOG Resources, Chevron, Devon Energy, Occidental Petroleum and Diamondback Energy.

Another US company, Enterprise Products, is the biggest transporter of NGL through its pipelines - running from oil wells to its port in Texas. From here, Stand.earth used an array of ship tracking data and company records to see where the vessels were unloading and who bought their cargo.

The two primary buyers were Indian multinational Reliance Industries and UK-headquartered INEOS - the world’s fourth largest chemical company and Europe’s biggest plastic producer. In the case of INEOS, some of the ship tracking was made easy by the fanfare around its ‘Dragon’ vessels, proudly emblazoned with ‘Shale Gas for Progress’ and ‘Shale Gas For Europe’.

It has subsidiaries at various stages of the supply chain. In Europe, INEOS turns ethane into ethylene, the world’s largest petrochemical feedstock, used to form polyethylene and PET - which end up in everything from plastic bags to bottles and clothes. It also acts as an intermediary in some polymer production - supplying chemicals to Dow Chemicals, for example, another major player in the network.

Stand.earth’s supply chain visualiser links INEOS directly to Procter and Gamble - a parent company with many brands under its name, like Always (menstrual products), Gillette and Olay. It also indirectly supplies Unilever, Coca-Cola, Nestle, and many other household brands.

The more links, the more likely a particular plastic item is made of petrochemicals derived from the Permian Basin, explains Dr Singh.

Ethane isn’t the only feedstock for plastic production. But there has been a shift away from using the primary alternative, an oil refining derivative called naphtha, in recent years. And with Europe producing only a small amount of ethane itself, the vast majority is shipped from the US - and the majority of that from Texas.

How could US and EU politics affect this supply chain?

Plastic is a supply-driven issue, the campaigners emphasise. “We know that there’s a correlation between the explosion of single-use plastic production from the beginning of 2000 and the boom in fracking in the US,” says Levi Alvares.

Despite consumers being guilt tripped over their plastic use, it’s this influx of cheap ethane that spurs on the industry to produce more, she says, and to create new markets when some close.

It remains to be seen how Trump’s second term will impact fracking, following an expansion under his first presidency. The US President’s command to “drill baby drill” isn’t necessarily music to the ears of fossil fuel producers since more extraction means more competition and lower prices.

“It potentially means that there will be more feedstock for petrochemicals production, and primarily for plastic,” explains Levi Alvares. “At the same time, there is a war on tariffs, so we don’t know how that’s going to play out in the fossil fuel trade.”

Meanwhile, Brussels is pushing to re-industrialise and decarbonise Europe to make it more competitive through the new Clean Industrial Deal. It’s an amenable environment for petrochemical companies to advance their plans, such as INEOS’s Project One in Antwerp.

If built, this would be the biggest ethane cracker in Europe - a plant that uses extreme heat to break the gas into ethylene and propylene. Project One has faced continuous legal challenges from ClientEarth and other green NGOs, which argue that authorities have failed to consider its full environmental impact.

With Europe cracking down on plastic consumption, CIEL argues there’s no clear demand for the facility.

“The price of EU competitiveness and supposedly decarbonisation is actually much different than what [decision makers] are willing to see, because you cannot decarbonise the EU petrochemical industry if the feedstock is coming from fracking in the US or oil extraction in the Niger Delta and so on,” argues Levi Alvares.

“Externalising environmental degradation and human rights violations is one part of the ongoing petro-colonisation that Gulf South communities are forced to shoulder,” says Yvette Arellano, founder and executive director of Fenceline Watch in Houston, Texas, a grassroots organisation.

“From toxic extraction in the Permian Basin to poisonous production along the Houston Ship Channel, the cost is irreversible damage to our children’s health - low birth weights and reproductive and developmental harm - spanning generations.”

Holding plastic companies accountable

First and foremost, the campaigners are calling for a reduction in the production of plastic.

“The single-use plastics that we are being inundated with in our life everywhere, when we have other options, are basically Big Oil’s way of continuing to push for the expansion of the fossil fuel industry,” says Dr Singh.

Brands, adds Levi Alvares, “are usually forgetting that their primary business is not packaging, it’s really bringing products to people, and so [using plastics] is a choice that they make. Therefore, they have a responsibility in terms of where this is coming from.”

CIEL and Stand.earth say their research is a step forward in transparency and should make brands look upstream when assessing plastic-related pollution. They say commitments about virgin plastic use have been getting weaker in recent years, making companies look “hypocritical” when supposedly demanding solutions.

Coca-Cola, for example, a leading member of the Business Coalition for a Global Plastics Treaty, announced it was dropping its voluntary virgin plastic use reduction goals just after talks about the treaty collapsed in December. The company’s plastic use is set to exceed 4.1 million metric tonnes a year by 2030, according to a new study from Oceana.

Although feedstocks often fly under the radar, petrochemicals are on track to become the largest driver of global oil and gas consumption, according to an IEA report on energy ‘blind spots’.

“Without transparency, restrictions on chemicals of concern, and clear caps on production, corporate polluters will continue to profit while communities bear the cost,” says Steven Feit, senior attorney and legal and research manager at CIEL. “We need a strong Global Plastics Treaty to cut plastic production and hold corporate polluters accountable across the entire supply chain."

A Unilever spokesperson says the company “purchases virgin plastic from a range of converters, which derive from petrochemical sources. Reducing our virgin plastic use is a priority, and last year we used more recycled plastic than ever before (21 per cent in 2024).”

Euronews Green contacted INEOS, P&G and Coca-Cola but they did not immediately respond to a request for comment.