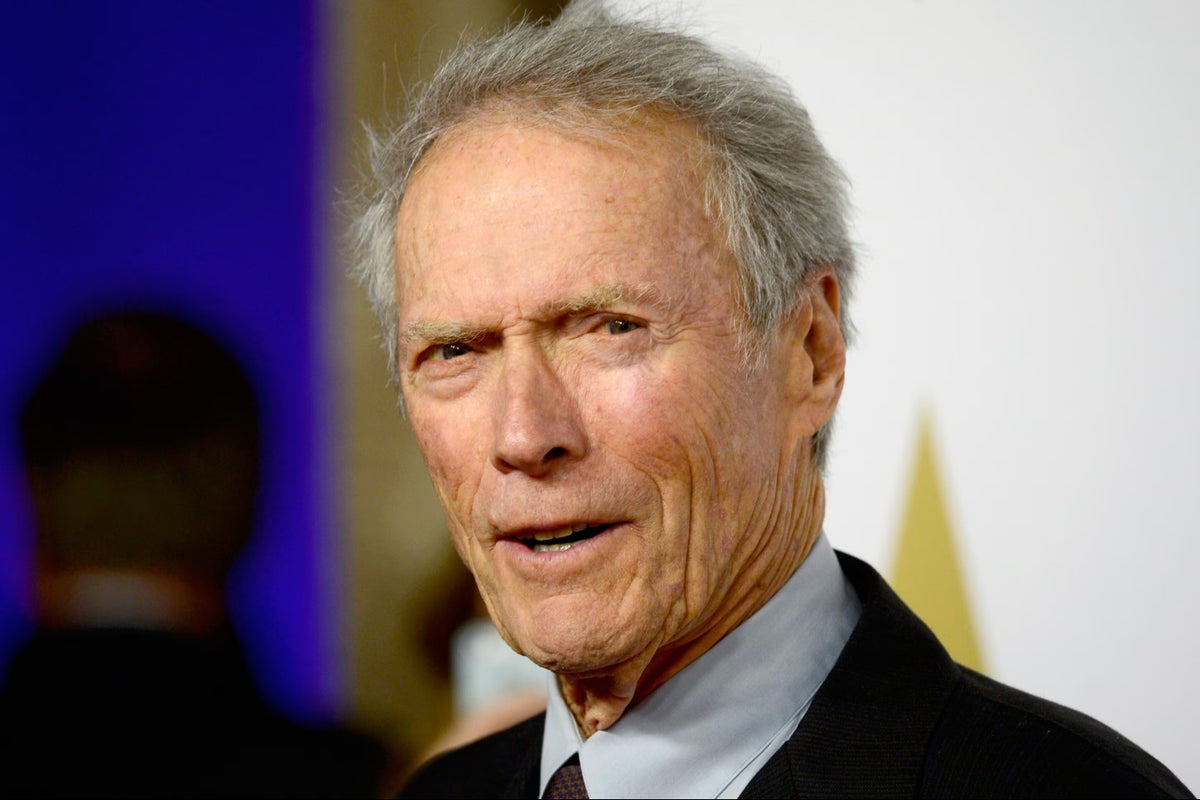

It’s hard to imagine cinema without Clint Eastwood. Born three years after the first “talkie”, the American actor and director has been alive almost as long as the medium itself. After finding rare success as a westerns actor – moulding an entire genre to his own hard-bitten image – Eastwood went on to become one of the most prolific and celebrated filmmakers around, directing everything from jazz biopics (Bird), to war dramas (Heartbreak Ridge), to romances (The Bridges of Madison County). Next year, Eastwood will be 95 years old. His latest film, Hitchcockian legal drama Juror #2, is his 40th. It’s a fittingly thoughtful capper to a truly remarkable career. So why, then, has this film been “buried”?

That’s the word being thrown around, at least. Juror #2, which stars Nicholas Hoult as an expectant father serving on a jury for a murder trial, is being released on just 50 screens across the US. In the UK, it’s also getting a limited release. It’s a sign, perhaps, of how Eastwood’s stock has fallen in recent years. It may be odd to suggest that a man who has won four Academy Awards doesn’t get the respect he deserves, but in Eastwood’s case, it may well be true.

Criticisms of Eastwood’s acting date back decades. The late Ray Liotta once named Eastwood as the most “overrated” actor of his time – and there’s certainly no shortage of others who agree. It’s true, of course, that Eastwood had his tics as a performer. The squinting, the gravelly stoicism: it’s no wonder he became such popular fodder for impressionists. But Eastwood’s best roles were also performances of considerable skill; he could communicate pathos and mystique like few others. Criticisms of his filmmaking chops, however, are somewhat more recent – a reaction to his middlingly received efforts post-Million Dollar Baby in 2004.

Look back at Eastwood’s late career output, and you can see where the disparagement is coming from. Anti-racism drama Gran Torino (2008) was trite and problematic; paranormal drama Hereafter was muddled and deflating. Leonardo DiCaprio-starring Hoover drama J Edgar was an outright disaster. There was a critical uptick with 2014’s American Sniper, which cast Bradley Cooper as a sanitised version of real-life Navy Seal Chris Kyle – but the film’s six Oscar nominations were overshadowed by talk of its uncomfortable racial politics, and one truly laughable scene involving a fake baby. Drug trafficking drama The Mule was rightly mocked for involving its nearly 90-year-old protagonist (Eastwood) in not one, but two whole threesomes.

And yet, not all of Eastwood’s late films can be written off quite so readily. Sully (2016), which cast Tom Hanks as beleaguered airline pilot Chesley “Sully” Sullenberger, who crash-landed a plane on the Hudson river, was a consummate win – a taut and surprisingly moving drama that played out like a meatier version of Robert Zemeckis’s Flight. Richard Jewell (2019) was another ripped-from-the-headlines drama, casting Paul Walter Hauser as a naive security guard who is accused of staging a terrorist incident. It’s a propulsive film, anchored by a terrific central performance. Responses to Juror #2 have been mixed, but some reviews have deemed it Eastwood’s best in decades. For all its contrivances, it’s a deftly made and quietly potent piece of work, made all the more interesting by its sheer old-fashionedness. It is the kind of film that no one is making anymore, a drama that wouldn’t have felt out of place 80 years ago.

But this may be part of the problem. The issue many people seem to have with Eastwood is that he is unfashionable. His films tend to be unflashy and classical in approach, even when they’re tackling contemporary stories and ideas. As a filmmaker, Eastwood sits somewhere on the boundary between auteur and gun for hire, less a stylist than a man of ideas. As a man, Eastwood is also politically unfashionable – a dyed-in-the-wool Republican in an industry where liberalism reigns. One of the enduring images of Eastwood in recent years is of the actor addressing an empty chair at the Republican National Convention in 2012, pretending that it was Barack Obama. (He later dismissed the much-discussed stunt, describing it as “that silly thing at the Republican convention”.) Eastwood has, however, been critical of Donald Trump, a caveat that has gone some way to softening his reputation in left-wing circles.

To some extent, Eastwood is simply a victim of our need for a neat narrative. What do we do with a man who has outlived his own legend? In 1992, Eastwood directed and starred in the revisionist western Unforgiven, a masterful rumination on – and deconstruction of – the genre that made his name. The film is Eastwood’s greatest achievement as a director, a work that stitches together the two halves of his career, that retroactively deepens and enriches all the gunslinging oaters that preceded it. There could hardly be a more fitting swansong, and the cinematic establishment knew it. Unforgiven won Oscars for Best Picture and Best Director, and saw Eastwood nominated for Best Actor.

Of course, this bittersweet farewell wasn’t actually a farewell at all. Twelve years later, Eastwood repeated the feat with Million Dollar Baby, a moving sports melodrama in which he plays a septuagenarian trainer who takes a plucky female pugilist (Hilary Swank) under his wing. The film took home Best Picture and Best Director, as well as Best Actress and Supporting Actor wins for Swank and Morgan Freeman, and another nomination for Eastwood’s performance. This, it seemed, was the swansong after all, a poignant triumph from an actor and filmmaker who was then well into his seventies. If you’d have told people back then that Eastwood still had 15 more films in the tank, they’d have surely thought you mad.

It has been speculated that Juror #2 really will be Eastwood’s final film. Sources close to Eastwood initially told outlets that he intended to retire after the film was completed; Toni Collette, who stars in it, subsequently claimed that Eastwood was already eyeing up his next project. At this point, he has nothing left to prove, no more statements to make. But he keeps on making films regardless. This is the ethos by which he has lived, for decades now.

It may be only once he’s gone that Eastwood’s career can be appreciated in its vast, winding totality. Only in his absence will it become obvious exactly how much he was bringing to the table. He is a relic in the best and most fascinating sense of the word, an artist from another lifetime who has lived to see and explore modernity. It’s a good job his career didn’t end when he rode off into the sunset – there was still a brand new day to enjoy.

‘Juror #2’ is out in cinemas now