More than a dozen heads of state of African countries are due to attend the first African Climate Summit as the continent seeks to assert a stronger voice on a global existential problem that it contributes the least to.

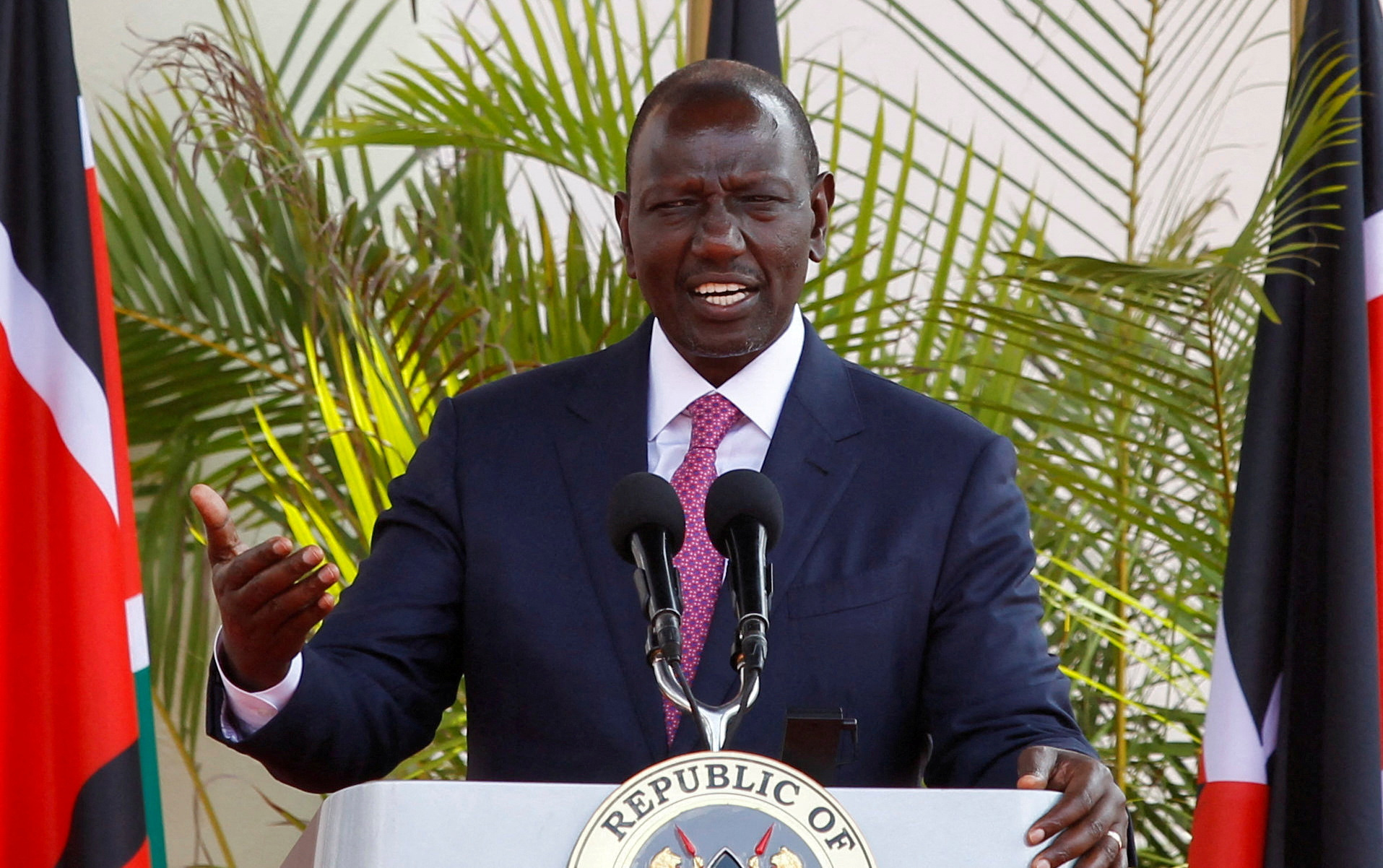

Kenyan President William Ruto’s government and the African Union launched the meeting on Monday in Nairobi, determined to wield more global influence and bring in far more financing and support.

“For a very long time, we have looked at this as a problem. There are immense opportunities as well,” Ruto said of the climate crisis, speaking of multibillion-dollar economic possibilities, new financial structures, Africa’s huge mineral wealth and the ideal of shared prosperity. “We are not here to catalogue grievances.”

And yet there is some frustration on the continent about being asked to develop in cleaner ways than the world’s richest countries, which have long produced most of the emissions that are heating the climate, and to do it while much of the support that has been pledged to Africa hasn’t appeared.

“This is our time,” Mithika Mwenda with the Pan African Climate Justice Alliance told the gathering, asserting that the annual flow of climate assistance to the continent is a tenth or less of what is needed and a “fraction” of the budget of some polluting companies.

More than $83bn in climate financing was given to poorer countries in 2020, a 4 percent increase from the previous year but still short of the $100bn annual goal set in 2009.

“We have an abundance of clean, renewable energy, and it’s vital that we use this to power our future prosperity. But to unlock it, Africa needs funding from countries that have got rich off our suffering,” Mohamed Adow with Power Shift Africa said before the summit.

Meanwhile, the advocacy group ONE campaign warned in a report released ahead of the summit that high-interest rates and lack of sufficient capital from bodies like the World Bank have made debt increasingly unsustainable for low-income countries and have held up financing for much-needed climate solutions.

“In addition to decreased health and social spending, that means they cannot harness their considerable resources to deliver climate solutions,” the report read.

Participants from outside Africa include the United States government’s climate envoy, John Kerry, and United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres, who has said he will address finance as one of “the burning injustices of the climate crisis”.

Ruto’s video welcome released before the summit was heavy on tree-planting but didn’t mention his administration’s decision this year to lift a years-long ban on commercial logging, which alarmed environmental watchdogs. The decision has been challenged in court while the government says only mature trees in state-run plantations would be harvested.

“When a country is holding a conference like we are, we should be leading by example,” said Isaac Kalua, a local environmentalist.

Kenya derives 93 percent of its power from renewables and has banned single-use plastic bags, but it struggles with some other climate-friendly adaptations.

Ruto made his way to Monday’s events in a small electric car, a contrast to the usual government convoys. He rode on streets cleared of the sometimes poorly maintained buses and vans belching smoke.

Despite the vast potential for solar and other renewable power in Africa, nearly 600 million people on the continent lack access to electricity . Other challenges for Africa include simply being able to avert thousands of deaths and billions of dollars in damage that, like climate change itself, have effects far beyond the continent.

“When the apocalypse happens, it will happen for all of us,” Ruto warned.