The rise and fall of the Tibetan empire could be closely linked to sun cycles, according to an international study.

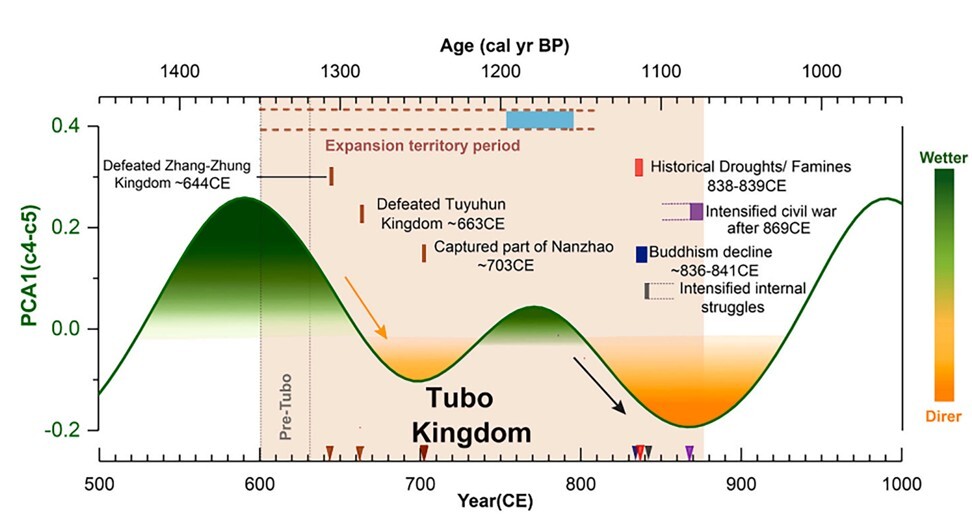

Unusually weak solar activity around 600AD brought more rain and snow to the Tibetan plateau, found the researchers, with the wetter climate helping create Tubo, the first unified empire in Tibet, in the mid-7th century.

By the 9th century, however, ultra-strong solar winds had upended the regional climate, causing famine and social unrest that led to the Tibetan empire’s epic collapse.

“There are many reasons contributing to the rise and fall of an empire. We found some clues not recorded in historic texts,” said a lead scientist of the study, Xu Deke, of the Institute of Geology and Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing, in a phone interview with the South China Morning Post on Wednesday.

The findings were published in the peer-reviewed Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology journal this month.

Early human fossils in Tibet were dated back to 160,000 years ago. Because of the harsh environment, communities there had long been divided into tribes and small kingdoms.

The sudden rise of the Tibetan empire changed the course of history in Asia. At their most powerful, Tibetan warriors controlled a big part of the ancient Silk Road, ransacked the capital city of the Tang dynasty and invaded the Indian subcontinent.

But the empire lasted only about two centuries, with some historians blaming its collapse on political infighting within the ruling class.

Others disagree.

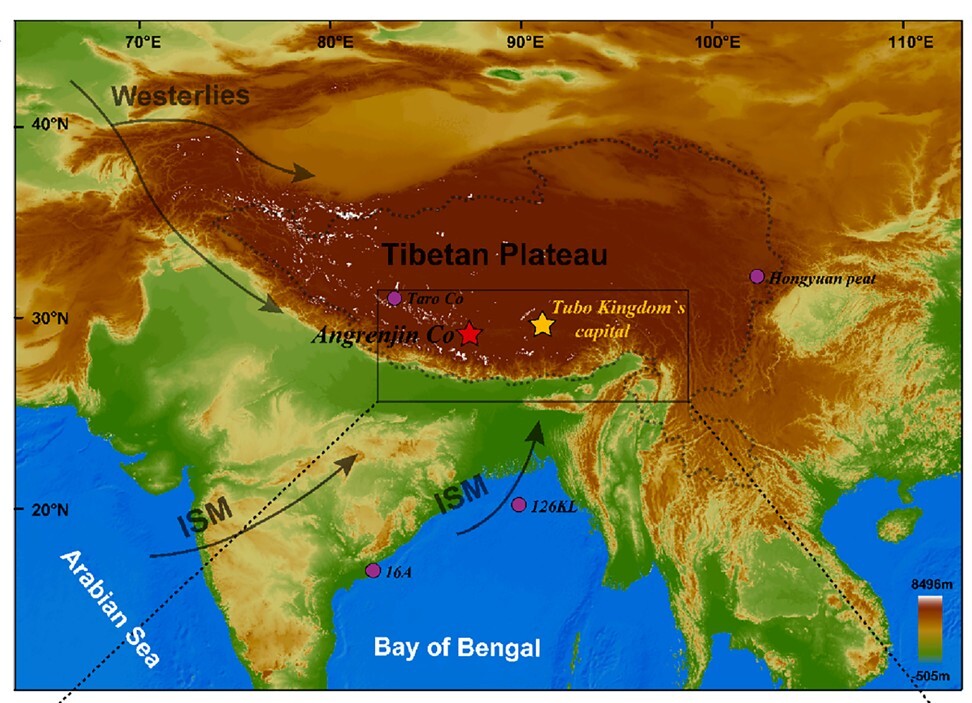

In 2011, Xu’s team retrieved a core of sediment samples from a lake 4,306 metres (14,100 feet) above sea level in southern Tibet.

The lake, Angrenjin Co, receives water from three rivers and has no outflow, so the sediment accumulating at the bottom of the lake serves as a faithful record of climate change for nearby areas.

Xu and his colleagues spent years counting and analysing the spores of different flowering plants. Some plants, such as artemisia, thrived in dry climates, while others, including cyperaceae, needed more water. The plant composition varied as the climate changed.

Using a combination of three methods, the researchers obtained dating data of the sediment samples, stating they achieved unprecedented accuracy.

“New technology such as AI-assisted spore counting and recognition is still under development, so most work still needs to be done by hand. We spent a lot of time on this study to make sure there are no mistakes,” Xu said.

The climate theory casting new light on Chinese civilisation

The spore data suggested that in southern Tibet, the heartland of the Tubo empire, the climate had been gradually drying up for at least 3,600 years.

But it was not a smooth process.

One exceptionally wet period from 550 to 650AD coincided with the formation of the Tubo empire through the unity of numerous tribes and kingdoms.

The young empire then encountered a relatively mild dry period. These small droughts, however, did not crush the resilient society but stimulated a series of military conquests and the application of new technology in agriculture that helped further expand Tubo’s territories and cultural influence.

The strength of the Tibetan empire reached its peak in the late 8th century, another relatively wet period. But nearly a century of extremely dry climate followed, and the empire fell apart to warring tribes and kingdoms by the mid-9th century.

“The drought was so bad, it was beyond tolerance,” Xu said.

The researchers found that the variation in the lake’s climate record matched the sun cycles almost perfectly.

The intensity of radiation from the sun to the Earth was not constant, but changed in a repeated pattern every few thousand or hundred years, or even decades, depending on the orbiting position, sunspots and the response mechanism of the Earth’s atmosphere.

Global warming may have started before industrial revolution, study says

There are numerous sun cycles with different lengths of time. Sometimes they could cancel out or reinforce one another.

The birth and death of the Tibetan empire occurred in the overlapping period of the 500 and 200-year cycles that made solar activities either extremely weak or extremely strong, according to the calculation by Xu’s team.

After the collapse of Tubo the climate turned wet again, but no powerful empire ever arose there again.

“Climate is an important driving force, but it does not explain everything in history,” Xu said.

Some previous studies found that China’s prosperity was closely linked to temperature. The most prosperous dynasties coincided with the warmest periods.

In the Tang dynasty, for instance, the Yellow River region was so warm and wet there were thick bamboo forests on river banks.

Some Chinese astronomers have predicted that the sun’s activities will decline over the next 250 years.

Researchers have already observed a trend of wetter conditions in some parts of western China, including Xinjiang and northern Tibet.

But whether – and to what extent – this process is affected by greenhouse gases released because of human activities remains unclear.