On the night of 13 January 1963, Togo’s President Sylvanus Olympio was shot dead by rebels in the first military coup staged in Africa. A long list, as shown below, was to come. From the 1960s to the end of the millennium, there were an average of four military coups a year on the continent. By the end of the 1990s this phenomenon seemed to have faded away.

But since August 2020 six African nations have suffered seven coups or attempted coups.

First came Mali, in August 2020. The military took advantage of social unrest and insecurity caused by the activities of violent extremists. Mali had two coups or attempts in a nine-month span.

In April 2021, Chad followed the same path. In March 2021, there was a coup attempt in Niger, and in September 2021 it was Guinea’s turn. A month later, it was Sudan. In Burkina Faso, an attack in November 2021 led to the coup in January 2022.

More recently, a coup was launched in Niger, deposing President Mohamed Bazoum. Two days later, General Abdourahamane Tchiani declared himself the leader of Niger.

All together, that’s more than 100 million people being ruled by the military after power was seized violently. All are in the Sahel. This has alerted governments in the region.

Researchers, analysts and journalists have pointed to mismanagement, incompetence, corruption, economic crisis and state weakness as the main factors propelling military coups all over the world and, of course, in Africa. State weakness is a factor in the recent instances in Africa. They have happened partly because of governments’ failure to stem the spread of groups linked to Al Qaeda and the Islamic State all over the Sahel.

Read more: Niger coup: why an Ecowas-led military intervention is unlikely

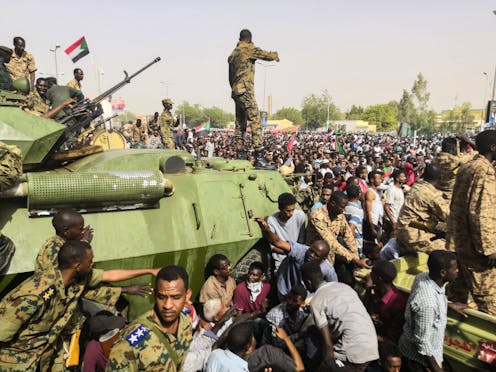

But there are two intertwined characteristics that differentiate Africa from the rest of the world. One is the public support of many citizens on the streets when there is a coup. The other is the society’s rising support for military rule as a form of government. Popular support for military rule has grown in the last 20 years.

My research explored the reasons for this. I used survey data to examine whether support for nondemocratic rule was mainly due to poor institutional and economic performance or to an existing so-called authoritarian personality and culture in the region. This type of personality refers to values existing in certain societies that make them more prone to embrace authoritarian forms of government.

This distinction is relevant because if the reason for military rule support is cultural, then societies will continue to endorse authoritarian regimes. If the reason is institutional performance, then as long as incumbent governments perform efficiently, both politically and economically, democratic support will overcome authoritarian support.

Citizen discontent

I carried out a quantitative analysis using Afrobarometer survey data gathered from 37 African countries, both from North Africa and Sub-Saharan Africa. The analysis looked for underlying factors propelling the rise in support for military rule.

Respondents were asked about the extent of their support for military rule as a form of government plus a number of other potential explanatory questions such as perception of corruption, governing and opposition parties performance, economy evaluation and socio-demographic issues like their level of education.

The data shows that from 2000 to the present, the level of support for military rule as a form of government has doubled, from 11.6% of people supporting “much” or “very much” military rule as a form of government to 22.3%. Of the 37 countries analysed, there were 11 where support for military dictatorship was decreasing and 26 where this figure was on the rise. The latest Afrobarometer data shows that support for democracy has fallen in the last year. Out of 38 countries, only four show decreasing support for military rule since 2000, whereas 34 show higher support for higher military rule than in 2000.

Support for military rule was higher in “partly free” and “not free” countries than in “free” countries. (They were categorised according to the Freedom House index.)

But there were some exceptions. In South Africa, which is a constitutional democracy with regular elections, one in three South Africans supported military rule as a form of government. In democratic Namibia the level of support showed that one in four Namibians supported military rule.

Reasons to support military rule

The analysis points to three conclusions:

In sub-Saharan Africa, the legitimacy of military rule is mainly based on institutional performance and economic management. These are weakened by jihadist organisations rapidly expanding throughout the region. State institutions are not able to tackle their expansion throughout the region.

In North Africa, institutional performance plays a role but authoritarian personality plays a larger role in the support for military rule.

Education seems to be an antidote against authoritarianism. Those with higher level of education, according to survey data, show higher level of democratic endorsement.

The study’s findings suggest that people in sub-Saharan Africa are fed up with their governments for many reasons, including security threats, humanitarian disasters and lack of prospects. Waiting for the next elections to take place to change government does not seem to them to be a good option. Opposition parties do not seem to enjoy a better image. For the survey respondents, the solution appears to be to welcome the military to intervene.

If citizens perceive that politicians don’t care about them, this will invite the military to continue overthrowing civil governments, with society publicly legitimising their intervention in politics.

If military, political and economic solutions are not found, military coups in the region will increase and people will continue gathering on the streets to welcome them. Niger’s recent coup may not be the last one.

Carlos García Rivero is Research Fellow at the Centre for International and Comparative Politics, at Stellenbosch University, South Africa.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.