If every country used as many resources every year as NZ does, we’d need three planets; our throwaway economy is a big cause of our emissions. We have to do things differently, says circular economy expert Debbie O’Byrne I Content Partnership

They call it Earth Overshoot Day - the day each year when the world goes into a state of environmental overdrawn-ness. When the amount of ecological resources we have consumed that year exceeds the amount the earth can produce in that same 12 months.

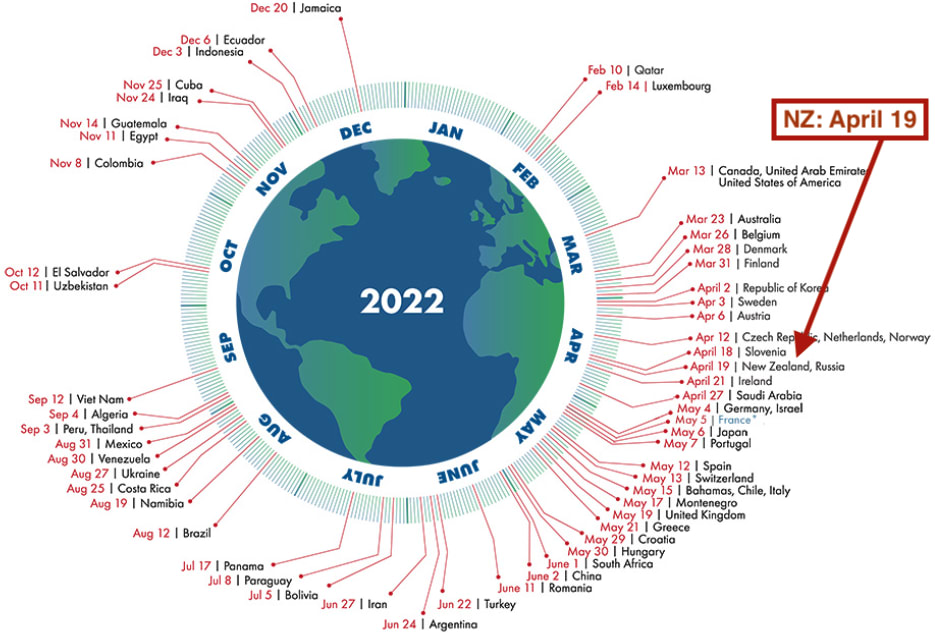

This year, Earth Overshoot Day, as calculated by the Global Footprint Network, was July 28. Put another way, we would need 1.75 planets to meet the world's total consumption of stuff this year, without borrowing from the future.

As the graph below shows, the situation gets worse and worse each year. Last year the date was July 29, in 2012 it was August 4, in 2002 September 21, in 1992 October 15, in 1982 November 19.

Earth Overshoot Day

Each year we consume a bit more of the planet’s ‘biocapacity’.

It hasn’t always been the case - we’ve been in annual ecological overdraft for only the past 50 years. In 1970 we were more or less at equilibrium - World Overshoot Day was December 30.

And in 2020, when worldwide Covid lockdowns kept humans at home and factories shuttered, the picture improved - just for one year.

Aotearoa’s number is worse than the global average - along with plenty of other industrialised countries. Our overshoot day this year was April 19, a date we share with Russia. Other countries that perform worse than us include the US, Australia, Qatar and Finland.

New Zealand is in the top 20 worst-performing countries

If the world’s population had the same lifestyle as New Zealand citizens, the resources of three planets would be necessary to ensure its existence.

“It’s not just carbon emissions,” says Debbie O’Byrne, circular economy principal with engineering and consulting company Beca. “It’s what we eat, how we travel, what we buy. It’s about energy consumption and all the metals and other raw materials extracted to make what we need for how we live.”

And don’t think New Zealanders can get away with the excuse we live at the bottom of the world so everything (and everyone) has to travel further, O’Byrne says.

“It’s a little bit of that, but mostly that’s a distraction. We just need to stop buying so much stuff.

“Some of us in countries with high standards of living are consuming way too much. We are using the resources of multiple people, multiple future generations.”

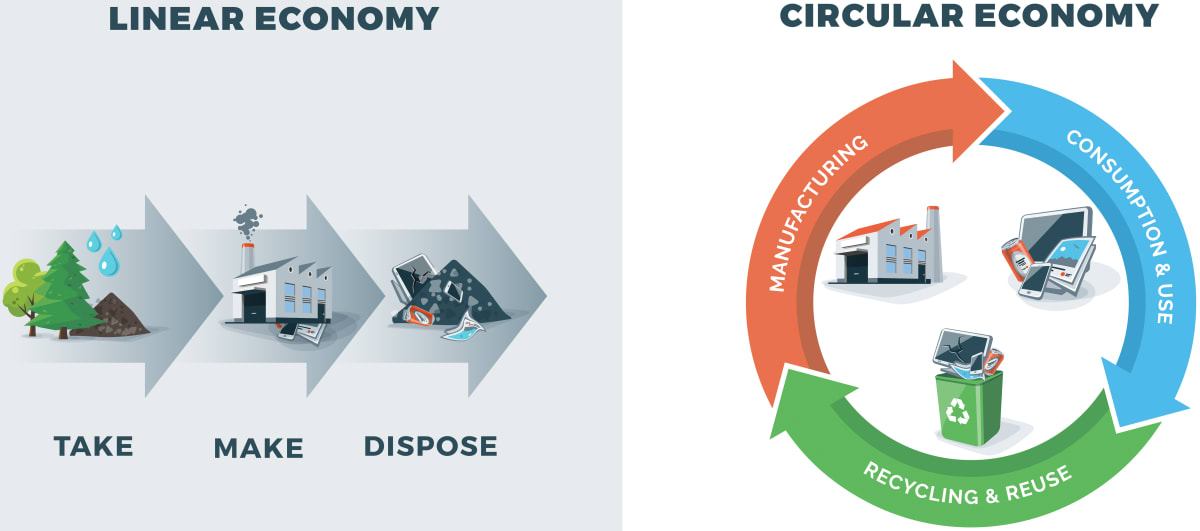

There is another way, O’Byrne says. We need to move from our largely “linear” economy - the idea of take-make-use-waste - to a more “circular” version.

The term 'circular economy' isn’t new - it was used in the 1960s by economist Kenneth Boulding. And often the real-world application of circular economic principles isn’t actually circular, in that you don’t return everything to its original state.

Instead the phrase has come to represent a system where we preserve the value of raw materials and the things we make from them for as long as possible. This means less waste, and hopefully fewer products needing to be made from new raw materials.

'Reuse', 'repair' and 'recycle' are the mantras of the circular economy, with the first two the more preferable options.

“It’s not just carbon emissions. It’s what we eat, how we travel, what we buy. It’s about energy consumption and all the metals and other raw materials extracted to make what we need.” Debbie O'Byrne, Beca

Because many products, including plastic, can’t be reused or recycled forever, the ‘circular’ economy can be more a spiral than a circle - it’s about keeping materials in circulation as long as possible in one form or another, delaying the need for new materials to be brought into circulation.

It’s appropriate that a model that involves guardianship of the world’s resources (kaitiakitanga) resembles a koru, O’Byrne says, given the strong connection between the te ao Māori lens and the basic principles of the circular economy.

In Māori, as in many Indigenous cultures, a key philosophy involves people thinking about the generations ahead and therefore taking only the resources they need at a particular time, so there is always enough left behind to regenerate.

“We had an amazing conference in Rotorua a few years ago; it was the world's first specific indigenous circular economy summit. And they actually challenged the notion of a circle - they called it a spiral. And that was very much a te ao Māori perspective,” O’Byrne says.

Whether circle or spiral, the idea of the circular economy is becoming more mainstream - and not just among environmentalists. In Ireland, where O’Byrne was born, a Circular Economy Act passed in July. Amsterdam has a Circular Economy Strategy 2020-2025 tied in with the city’s plans to be climate neutral by 2050.

And New Zealand? We are further behind, but there’s a circular economy chapter in the Emissions Reduction Plan released in May. It’s a bit vague, but it’s there as a target.

“By 2050, Aotearoa New Zealand will have a circular economy with a thriving bioeconomy that seizes the opportunities from global trends and shifting consumer preferences,” the plan says.

Meanwhile, the circular economy is one of five key focus areas in the Infrastructure Commission’s 2052 strategy. “It’s finally starting to trickle out, and that’s really good because it exposes a wider audience to the concept,” O’Byrne says.

But it needs more than individuals and businesses doing things differently; it’s about changing whole systems, she says.

Circular solar

Take solar panels and electric batteries. They are great for the environment in terms of producing renewable energy, cutting the need for fossil fuels, and reducing emissions. But they are energy- and emissions-intensive to produce, and they are mostly thrown away once they stop working, wasting a whole lot of valuable materials they contain - silver, copper, aluminium, silicon, and glass in terms of solar panels, and lithium, cobalt, nickel, copper, aluminium and iron in lithium ion batteries.

An article in Climatebiz.com suggests 96 percent of a lithium ion battery can potentially be recycled, but only 5 percent of solar batteries are actually recycled.

“You have to come at it from the beginning and give yourself a big hairy audacious goal that this panel will never end up in landfill, so what would that look like?" - Debbie O'Byrne, Beca

Solar energy has the potential to be circular, O’Byrne says, but we have to think about circularity right through the whole industry.

“We need to look at the beginning, designing out waste when you make the panels, and then you have to make them easy to disassemble, so the resources that are still really useful and valuable aren’t damaged by being glued or put together in a way that makes the second or third iteration of their life really hard.

“You have to come at it from the beginning and give yourself a big hairy audacious goal that this panel will never end up in landfill, so what would that look like?

“And it’s a systems issue - a supply chain issue, and a processing issue and also about regulation.” Because often, without regulation making it compulsory, first mover advantage can prove quite the reverse.

At the moment, sending a solar panel to landfill is far cheaper than recycling it - even where recycling technology is available.

Designing out planned obsolescence

Circularity is already creeping into some sectors - and not necessarily where you’d expect. Like plane engines and street lighting.

Rolls-Royce sells a majority of its jet engines on service contracts instead of customers paying upfront. Under these contracts, airlines pay Rolls-Royce per hour of flying time and as a function of the engine’s efficiency.

Which means instead of it being in Rolls-Royce’s best interest to sell customers new engines as often as possible - involving using more raw materials - the company is incentivised to keep engines on planes as long as possible and at maximum efficiency.

It’s a similar scenario with Dutch lighting-turned-consumer-electronics-turned-healthtech company Philips. A circular lighting model offers customers the option to pay only for the light they use, not for the lamps and the bulbs. Philips looks after the installation, performance, and servicing of a company - or a district’s - lighting, meaning once again it is incentivised to reduce waste and encourage longevity.

It’s a far cry from the Philips which, in the 1920s, was a founder member of the notorious Phoebus Cartel of light bulb manufacturers. The cartel colluded to make light bulbs that were fragile enough that they would burn out after a while - one of the earliest and most notable cases of planned obsolescence.

Circular construction

The construction sector is another example of where circularity could be built into the design, building and demolition process and make a huge difference in terms of greenhouse gas emissions and waste, O’Byrne says.

The ‘built environment’ accounted for 15 percent of New Zealand’s total greenhouse gas emissions in 2021, with construction and demolition waste accounting for approximately 50 percent of everything going to landfill, according to Kāinga Ora’s Sustainable Finance Framework.

While few people design a building for obsolescence, when its ownership or use changes, or a tenant’s design sensibilities evolve, a space can be deemed unsuitable, its residual value is not recognised, and it is consigned to premature demolition, O’Byrne says.

“Many buildings are put up today in such a way we can see the wrecking ball of the future already in the design.”

The circular economy version of demolition and rebuilding (both of which produce significant waste and carbon emissions), involves repurposing the structure and/or reusing the materials, O’Byrne says.

“There has been a trend towards greater re-use of existing buildings, but this needs to accelerate rapidly, and any new work needs to have an end-of-life pathway backed in from the start.

“We need to earn the right to build a new building.”

“Many buildings are put up today in such a way we can see the wrecking ball of the future already in the design.” Debbie O'Byrne, Beca

Sometimes called ‘adaptive reuse', this model is about taking a building that's past its prime, renovating the core structure, and redesigning it for new purposes.

Beca is part of the project team involved in redesigning the 50-year-old University of Auckland social sciences building known as B201, together with Jasmax Architects and a team from the university. The project has meant that instead of being demolished and rebuilt, with all the old materials sent to landfill and all new materials used, the building gets repurposed with a six Green Star design rating - the highest environmental standard in the country.

Emissions for construction and operation over its lifetime will be almost 60 percent less than an equivalent new build, according to Richard Walsh, Beca’s technical director and project lead for B201.

The building will send less waste to landfill, create less pollution through its construction and operation, and provide healthy, comfortable, and functional spaces for students and staff, he said.

Design for disassembly

But that requires the thought processes behind each new building allowing re-purposing and reuse.

“We need to be thinking ‘How do we design this so when we want to go and use those materials again in 40 or 50 years, we’ve gathered the right information.'" O'Byrne says.

“We’re pretty good at floorboards and tiles and sash windows, but we need to know exactly what every part of the building is made of, what its performance capabilities are, what that material has been used for.

“You need to make sure when you are building, you are capturing the data about the materials and products, so this data can be used to inform decisions and protect the value of the asset across its whole life cycle - and beyond.”

The first thing to do is design for flexibility - when in 30 years’ time a company wants to completely rework its office space, it can do so without tearing everything out and throwing all the materials away.

“Make sure the services [wiring, plumbing etc] are put in in such a way you can move the walls and it doesn’t matter.

“And when you really do need a new building, the old one should be designed so it’s easy to disassemble - no plastering or glues.

“Use a different design methodology so it’s easier to get down.”

O’Byrne imagines each component of a building containing a chip or code linked with a digital twin of the whole structure, so it can be deconstructed.

The advantages are obvious when it comes to adapting for climate change - lifting buildings, for example, or even moving them to a new location.

She says the construction sector could adjust if the rules were changed so circularity was mandated.

“It’s a different way of thinking. It changes your constraints, but engineers and designers and architects are problem solvers; they are used to dealing within constraints. Their main constraint, historically, has been the financial budget; now it could be the carbon budget, or maybe broader - the planetary budget.”

Beca is a foundation supporter of Newsroom