Everyone thinks they can do the Christopher Walken voice. That New York lilt. That round, honeyed purr, like a cat with plans. Try it yourself. Go on. Speak from the back of your throat. Elongate those vowels. What you shouldn’t do, though, is try it in front of him.

“People come up to me in the street and they impersonate me to my face,” Walken says. “You know, they speak the way I speak.” The actor, 81 and spry, looks knowingly down the lens of his Zoom camera. “And I’m never sure what they’re doing at first. I think, ‘Why is he talking that way?’ But then I realise.” He lets out an ambivalent whine. This sounds a little cruel, I tell him, while fully aware that I was speaking pure Walkenese to a colleague mere minutes before our interview. “Oh, it happens all the time,” he sighs.

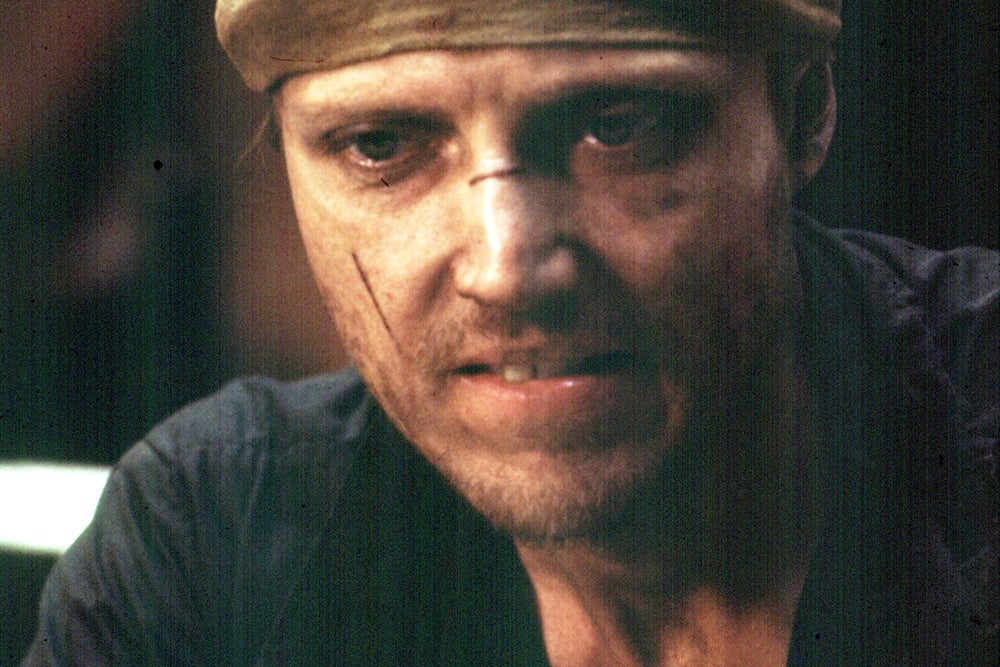

Put aside the invasiveness, though, and I suppose it’s a compliment. Abstruse, eerie, often impossible to pin down, Walken has existed outside of regular ol’ superstardom for decades now – today he’s, what, myth? A voice to be emulated. An image in a rap lyric. A dancer in a Fatboy Slim video. On-screen, he can be cool, psychotic, slippery, wise. An offbeat talker; a light mover. He’s played an emperor in Dune, an ant in Antz, and murderers in many things. He was the King of New York. Few actors can say they feature in some of the greatest films of all time (Pulp Fiction; Annie Hall; The Deer Hunter) and some of the worst (Gigli; Kangaroo Jack; that one where Kevin Spacey turned into a cat). But then few are Christopher Walken. Except for on TV. Where, up until very recently, there were two.

In Severance, the Apple TV+ Rubik’s cube that’s currently in the midst of its second, head-spinning season, employees of a mysterious biotech company have their lives split in half: one side of themselves exists in the world as we know it, with families, loved ones and hobbies; the other exists only within the walls of the workplace. Ne’er the twain shall meet – or even remember anything from the other’s space. But for ostensibly platonic colleagues Burt and Irving (played with such sweet, mature longing by Walken and John Turturro, both of whom received Emmy nominations for their work in 2022), something ambiguous hangs between them – either a romantic attraction that already exists on the outside, or something they want to make real on the inside.

“John and I – we’re not unlike a married couple in real life,” Walken laughs. The pair have known each other for close to four decades, first meeting at a party for the Yale Drama School sometime in the early Eighties (Turturro had just graduated; Walken was passing through). They’ve worked on films together, too – usually scrappy little comedies such as 1995’s Search and Destroy or The Jesus Rolls, Turturro’s strange quasi-sequel to The Big Lebowski from 2019. But even though Severance often keeps them apart – Burt retired at the end of season one, meaning his two lives have been reduced to one – it’s the most they’ve worked together so far. “We’ve had our ups and downs together,” Walken continues. “And when you can finish off each other’s sentences or laugh at each other’s jokes, it counts for a lot when you’re playing parts like these.” He smiles. “You can tell when people like each other.”

Walken is talking to me from New York, dressed in a black blazer and navy shirt, his hair grey, coiffed and tall, like he’s been electrocuted. We’re speaking before Christmas, our conversation taking place more or less with an Apple-branded dart blaster aimed at us: I’ve seen five episodes of the long-in-the-works second season at this point but have been forbidden to talk about their specifics. Today, viewers will know that Burt has been largely absent since the show’s return, existing solely in the real world following his retirement. Irving, meanwhile, has been left heartbroken in the wake of discovering that Burt’s “outie” – as opposed to his workplace “innie” – is married to a man who isn’t him. They’ve been kept apart until this week’s episode, which saw the pair finally meeting in the real world and Burt inviting Irving to eat dinner with him and his husband (a cryptic John Noble). It was a lovely reunion, albeit with strings attached. Their scenes remain some of the show’s best: tender, romantic, unexpectedly, well, erotic.

He brought Tarantino over. And I remember he was kind of shy and he looked about 12

“It’s been different for me,” Walken says. “Usually I’m up to no good in movies, but now I’m playing a nice, romantic person.” And gay, which is a first. Not that it’s a big deal, he says. “The truth is that I don’t really make a distinction there. Straight? Gay? That’s never been very interesting to me. People love each other.” He shrugs.

It’s the “nice” part that he finds most surprising. “Because it’s much more up my alley than all those other parts I’ve played,” he says. Meaning the psychopaths. Remember when he pushed Michelle Pfeiffer out of a high-rise window in Batman Returns, or played the Headless Horseman in Sleepy Hollow? And that’s just two of many. “Oh, it started way back,” he laughs. “One of the first things I did was Annie Hall, where I played this guy who wants to drive into traffic. Then I made The Deer Hunter, where I shot myself in the head. And then I just got identified with, you know, people who are troubled… to say the least.” Deeply unlike him, he insists. “The facts of my life are that I’ve been married for over 50 years, I pay my bills, and I live in a house. I’m a very normal person.”

He doesn’t even get upset very often. Especially when he’s on set. “It’s rare to work with someone you don’t like,” he explains. “It’s happened once or twice, but it’s rare. Actors tend to get along. We’re like a tribe, a family. Every once in a while there’s somebody you’d like to push down the stairs, but…” Now there’s a bit of classic Walken villainy, I tell him. “I swear it’s only ever a passing thought.”

Spend just a little time with him and you find yourself wanting to crack the Walken code. Not because he’s got walls up, but because no one else is really like him – he’s otherworldly, surprising, a little mystical. Sean Penn once remarked that attempting to define Christopher Walken is akin to “trying to define a cloud”. And the privacy only adds to that. He’s been a pop culture staple since the Seventies, but he retains a degree of mystery. Did you know that his name’s not even Christopher? “It’s a Severance kind of thing,” he laughs. “I’m Christopher, but to a small group of people, I’m Ronnie.” Those people include his closest friends and his wife, the former casting director Georgianne Walken, whom he married in 1969.

The enigmatic Ronald Walken was born in Queens, New York, to a mother and father who’d emigrated from Scotland and Germany, respectively. The facts of his biography are often so wild that they sound made up. But Walken was a child actor from the age of five, did run away to join the circus, did tame lions, and was advised to make Christopher his stage name by a nightclub dancer in the early Sixties. Theatre beckoned soon after, followed by a run of film hits in the Seventies: he played an artistic lothario in the comedy Next Stop, Greenwich Village; Diane Keaton’s unhinged brother in Annie Hall; the tragic Vietnam veteran of The Deer Hunter, for which he won a Best Supporting Actor Oscar in 1979. The latter propelled him to leading man status. He is marvellously haunted in the 1983 Stephen King adaptation The Dead Zone, as a schoolteacher struck by premonitions of the future, and a vision of paternal cruelty in the crime thriller At Close Range, released in 1986.

Some of the greatest Walken roles, though, are the supporting gigs or tiny cameos that rapidly became his bread and butter: the sleazy record exec in Wayne’s World 2, a sinister nightcrawler in Abel Ferrara’s vampire tale The Addiction, the cranky exterminator in Mousehunt. There’s a real softness to him at times, too. Look at Steven Spielberg’s Catch Me If You Can. Come for Walken as the slick, deceptive father to Leonardo DiCaprio’s fledgling conman, stay for the panicked vulnerability he lets peer out as the film goes on.

“My favourite part of being an actor, really, is the time I spend by myself, learning the scripts, studying them, learning lines,” he says. “It takes me for ever to learn lines, so to stand in my kitchen with the script is kind of as good as it gets.”

Unlike Burt in Severance, Walken’s not tempted by retirement himself. “Acting is all I do,” he says. “If I stop, what would I do? There are people who play golf, who write books. They travel, have kids and grandkids. I don’t have any of that, so I go to work. But when you look at the history of movies and theatre, very few actors ever say they’re done.” I tell him I can only think of Sean Connery who officially retired, packing it all in after a bad experience on a film. “But he was a big golfer,” Walken says. “So he had something to do.” He taps his chin, thinking. “I don’t play golf.”

Directors sometimes retire, he adds. “Quentin said somewhere that he wasn’t going to make any more movies, but I hope that’s not true.” He’s talking about Tarantino, who pledged a few years ago to make just one more film – bringing his filmography to a total of 10 movies – before throwing in the towel. The pair go back a while, Walken reciting two of Tarantino’s most famous monologues on screen, first the speech about the Sicilian mafia in True Romance – which culminates in Walken blowing Dennis Hopper’s brains out – then the ludicrous, scatological backstory of a military man’s gold watch in Pulp Fiction. There’s an old quote from Tarantino, from around the time of True Romance, where he said he felt “embarrassed” that Walken had spent months fastidiously learning his lines until they were note perfect. “It was almost intimidating that such a terrific actor would take my work so seriously,” he said.

Walken remembers doing much the same for his Pulp Fiction role. “I had the speech for about four months, and I think it was eight pages long,” he says. “And no matter what else I was doing, I would spend an hour a day going over that speech and gradually learning it. And every time I got to the end of it, it would make me laugh. Because his dialogue is all there on the page.”

They were introduced by a mutual friend, the actor Harvey Keitel. “I was staying at the Chateau Marmont at the time, and Harvey said to me, ‘There’s this guy you’ve got to meet, he’s brilliant,’ and he brought Quentin over. And I remember he was kind of shy and he looked about 12.” Walken hoots. “And I thought, you know, Harvey had discovered this Orson Wellesian teenager. Anyway, he’s terrific.”

He’s always had an eye for young talent. He bonded with Penn while filming At Close Range in 1985, and then his girlfriend at the time, a pop star supernova named Madonna. “I spent a lot of time with her because she’d be on the set, and I liked her very much,” he says. Soon after, he attended the pair’s nuptials. “It’s the only wedding I’ve ever been to where people were jumping out of bushes with cameras and there were helicopters flying overhead,” he laughs. “It was also the noisiest wedding I’ve ever been to.”

Years later, and long after she and Penn had split, Madonna called Walken up asking him to appear in one of her music videos. She had the perfect part for him to play.

“It was the Angel of Death,” Walken smiles, wry and spooky.

“Because who else?”

‘Severance’ is streaming on Apple TV+, with new episodes released every Friday