At first glance the only thing that China and cheese seem to have in common are their first two letters. When one thinks of Chinese food traditions, cheese doesn’t come to mind as it would do for countries like France or Italy.

Yet China has a long history of making savoury cheese products. Most are made in peripheral regions where ethnic minorities have been fermenting or culturing milk from various animals for centuries.

And although cheese consumption is not mainstream in China, it is catching on as more people have discovered the health benefits of dairy products.

“There was a widespread cheese culture in China from at least the Tang dynasty,” says Miranda Brown, professor of Chinese studies in the department of Asian languages and cultures at the University of Michigan in the US, who has carried out extensive research and published papers on Chinese cheese. The Tang dynasty ran from 618AD to 907AD.

“These are not rennet cheeses, they are either yogurt cheeses or some kind of acidic cheeses. There are some acid-activated varieties in Yunnan today. The best known example of this is the rubing from Yunnan, a soft cheese with soured quince juice.”

The latter is made from goat’s milk by the Bai people, an ethnic group that also produces rushan from cow’s milk that is stretched like elastic elongated looped mozzarella, wrapped around sticks and dried in the sun.

In Yunnan, cheese is made using fresh milk from yak, buffaloes, cows and goats. In Tibetan areas, and in Mongolia and Xinjiang, cheese is mainly made from yak, sheep and cow milk. Tibetan yak cheese comes in many shapes and types, but is typically used in fresh snacks sold to eat on the go. Members of Xinjiang’s Muslim Uygur minority has been making a semi-hard cheese called askuru for centuries.

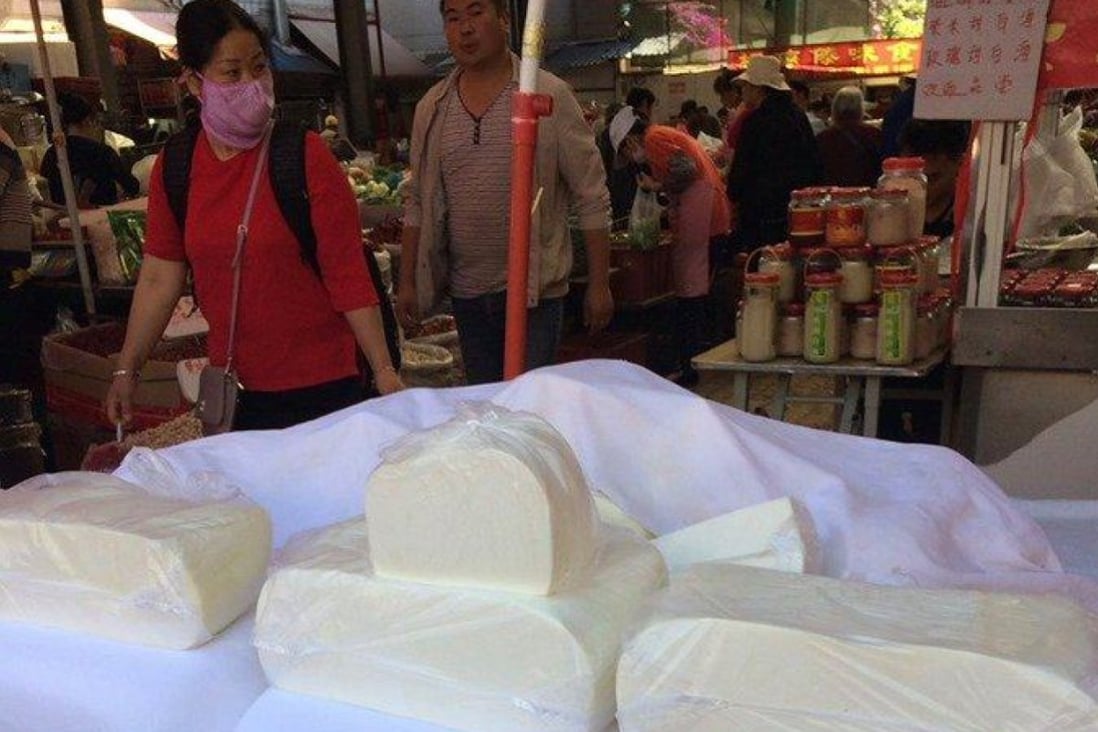

There’s also a special kind of buffalo milk cheese made in Shunde, Guangdong, while in Zhangzhou, close to Xiamen across the Taiwan Strait from Taiwan, cheese is produced that resembles mozzarella balls. Brown says: “Coagulated with vinegar, this niunai li cheese was taken to Taiwan with Chinese emigration in the Qing dynasty.”

How China is falling in love with cheese – from soft to blue

She adds: “I suspect that all of these traditions came to China in the medieval period from the outside world – potentially from Mongolia or even the Persian areas of Central Asia – or from what are today ethnic minorities.

“Certainly, people associate the cheeses in Yunnan with ethnic minorities like the Bai and Yi peoples. But the cheeses in Shunde and Zhangzhou are made in Han Chinese areas. They’ve been in China a long time, almost as long as dumplings.”

Brown explains that there was a widespread cheesemaking tradition in the broader Jiangnan (Shanghai) region until the end of the Ming dynasty; this was documented in a 16th century cookbook whose title translates as Mr Song’s Book of Nourishing Life, which shows how wealthy families relished their cheese – eating it stretched, fresh, preserved, lightly seasoned or breaded. They ate it inside dumplings and pastries, and with pork, fish and shellfish.

The buffalo cheese in Shunde, near Hong Kong, has a peculiar story. One legend goes that Jesuit missionaries brought it from Italy to southern China in the 1500s. This cheese is deeply rooted in working class culture. Veronica Mak, assistant professor at the sociology department of Hong Kong Shue Yan University and a dairy and cheese researcher, has written extensively on the topic.

“The indigenous cheese making in Shunde is a small, low-margin, labour-intensive and declining business with a shrinking market. Young people do not like to eat the local buffalo cheese, known as niuru, even though it started as an elite delicacy,” says Mak.

Sold in the form of thin slices, crispy and fragrant, niuru is usually packed in piles and bottled in brine. It is probably the most ancient buffalo milk product in Shunde, and Mak says that local people believe niuru has been consumed since the Ming dynasty.

The high fat content of buffalo milk makes it an ideal ingredient to produce good cheese and butter, but what makes the cheese of Shunde special is that it is made from swamp buffalo, which produce a rare and precious milk that is lower in yield compared to cows and ordinary river buffalo. Buffalo milk tends to be more savoury and has more of a salty edge than cow’s milk. Yak milk is similar in its nutritional properties to buffalo milk.

In Daliang, a subdistrict of Shunde, all the artisan cheesemakers are women, who pass down the craft from mother to daughter, explains Mak. They use white vinegar, not rennet, to curdle the milk. They produce niuru mostly in small workshops where they heat buffalo milk to around 30 to 40 degrees Celsius.

Milk is collected in a small porcelain cup and mixed with a small amount of white vinegar warmed in a ceramic pot. The women stir the mixture in a clockwise direction with their index and middle fingers. Immediately, curds form, which are poured into wooden moulds. The cheesemaker squeezes out the extra water using her left palm, yielding a piece of white, semi-transparent cheese about 5cm in diameter. It’s taken from the mould and placed in brine in a porcelain container.

Mak says that there are no historical records that back the story of Jesuits importing the knowledge of cheesemaking to Shunde, despite the cheese’s similarities to Italian buffalo cheese products such as mozzarella, burrata and robiola.

She explains: “From my research, I found that Shunde buffalo cheese originates from the ancient recipe for rufu. Rufu and rutuan are two kinds of milk curds listed in Chinese food literature from the Tang and Yuan dynasties (1271 to 1368) respectively. Rufu is curdled with vinegar, while rutuan uses naturally forming lactic acid. Rufu made from different kinds of milk were believed to have different medicinal properties.”

Mak says that according to tradition, dairy products needed to be eaten at particular times based on one’s health and according to the principles of traditional Chinese medicine. “Cheese made from buffalo milk was ‘cooling’ and suitable for the ‘hot’ body, while yak milk cheese was ‘warming’ and suitable for the ‘cool’ body type. Both were considered to be nutritious for the body and good for digestion,” she says.

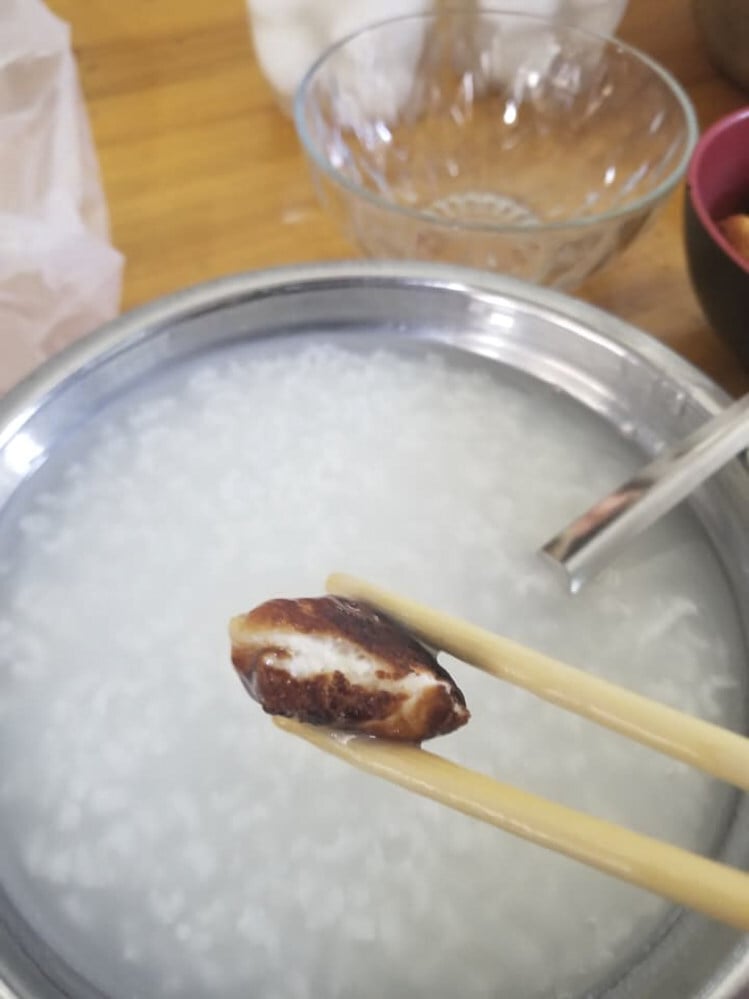

Another interesting cheese is made about an hour’s drive from the Ragya monastery on the Tibetan plateau. Cheesemakers produce a range of cheeses twice a day, which are processed at local dairies an hour after milking, using copper vats that are heated by burning dung.

The cheeses made in these extreme conditions showcase the excellent pasture of the region. Yaks yield low quantities of dense, rich milk that can have as much as seven per cent fat. This milk has a flavour similar to that of sheep’s milk in spring. The cheese can taste like a rough Italian sheep’s milk pecorino with a strong, grassy aroma tempered by the milk’s richness.