Chinese researchers have unveiled a new deep-sea tool capable of cutting through the world’s most secure subsea cables − and it has many in the West feeling a little jittery.

The development, first revealed in February 2025 in the Chinese-language journal Mechanical Engineering, was touted as a tool for civilian salvage and seabed mining. But the ability to sever communications lines 13,000 feet (4,000 meters) below the sea’s surface − far beyond the operational range of most existing infrastructure − means that the tool can be used for other purposes with far-reaching implications for global communications and security.

That is because undersea cables sustain the world’s international internet traffic, financial transactions and diplomatic exchanges. Recent incidents of cable damage near Taiwan and in northern Europe have already raised concerns of these systems’ vulnerabilities − and suspicions about the role of state-linked actors.

The growing sophistication and openness of underwater technology evidenced by the latest news from China suggest that undersea infrastructure may play a larger role in future strategic competition. Indeed, this development adds a new layer to the broader challenge of securing critical infrastructure amid expanding technological reach and the rise of so called “gray zone” tactics – antagonisms that take place between direct war and peace.

The backbone of global communication

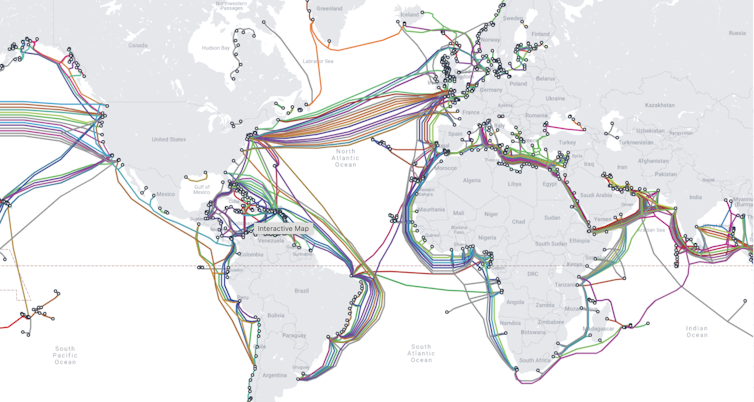

Despite their unassuming appearance, undersea cables form the backbone of modern communication systems. Stretching around 870,000 miles (over 1.4 million kilometers) across every ocean, these cables transmit almost 100% of global internet communication.

These information superhighways are a major engine for the modern economy and are indispensable for things such as almost instantaneous financial transactions and real-time diplomatic and military communications.

If all these cables were suddenly severed, only a sliver of U.S. communication traffic could be restored using every satellite in orbit.

The entire system is built, owned, operated and maintained by the private sector. Indeed, approximately 98% of these cables are installed by a handful of firms. As of 2021, the U.S. company SubCom, French firm Alcatel Submarine Networks and Japanese firm Nippon Electric Company collectively held an 87% market share. China’s HMN Tech holds another 11%.

Tech giants including Amazon, Google, Meta and Microsoft now own or lease roughly half of the undersea bandwidth worldwide, according to analysis by the U.S.-based telecommunications research group TeleGeography.

Vulnerabilities and sabotage

The very characteristics that make undersea cables effective also render them highly vulnerable. Built to be lightweight and efficient, they are exposed to a variety of natural hazards, including underwater volcanic eruptions, typhoons and floods.

But human activity is still the primary cause of cable damage, whether it’s from accidental anchor drags or inadvertent entanglement with trawler nets.

Now, security experts are increasingly concerned that future human disruptions might be intentional, with nations launching coordinated attacks on undersea cables as part of a hybrid war strategy.

Such assaults could disrupt not only civilian communications but also critical military networks.

An adversary, for example, could cut off a nation’s command structures from intelligence feeds, sensor data and communication with deployed forces. The ramifications extend even to nuclear deterrence: Without reliable communication, a nuclear-armed state might lose the ability to control or monitor its strategic weapons.

The loss of communications, even for a few minutes, could be catastrophic. It could mean the difference between a successful defense and a crippling first strike.

Geopolitical threats

In recent years, Western policymakers have become particularly concerned about the capabilities of Russia and China to exploit the vulnerabilities of undersea cables.

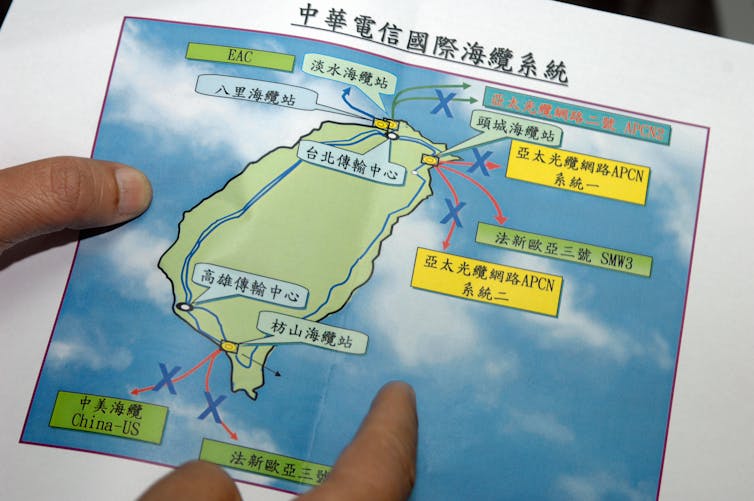

One particularly illustrative incident occurred in 2023 when Taiwanese authorities accused two Chinese vessels of cutting the only two subsea cables supplying internet to Taiwan’s Matsu Islands.

The resulting digital isolation of 14,000 residents for six weeks was not an one-off episode. Taiwan’s ruling Democratic Progressive Party has pointed to a pattern, noting that Chinese vessels have disrupted cable operations on 27 occasions since 2018.

In January 2025, Taiwan’s coast guard blamed a Cameroon- and Tanzania-flagged vessel crewed by seven Chinese nationals and operated by a Hong Kong-based company when an undersea cable was severed off the island’s northeastern coast.

Such incidents, often described as gray-zone aggression, are designed to wear down an adversary’s resilience and test the limits of response.

China’s recent push to enhance its cable-cutting capabilities coincides with a surge in its military drills around Taiwan, including a number of recent exercises.

Similar cable disruptions have occurred in the Baltic Sea. In October 2023, a telecom cable connecting Sweden and Estonia was damaged along with a gas pipeline. In January 2025, a cable linking Latvia and Sweden was breached, triggering NATO patrols and a Swedish seizure of a vessel suspected of sabotage tied to Russian activities.

Dmitry Medvedev, deputy chairman of Russia’s Security Council, even hinted at the possibility of targeting undersea communication cables as retaliation for actions such as the Nord Stream pipeline explosions in 2023.

The involvement of state-linked vessels in incidents operating under flags of convenience − that is, registered to another country − further complicates efforts to attribute and deter such attacks.

It isn’t just security and defense at risk. The modern financial system is predicated on the assumption of continuous, high-speed connectivity; any interruption, however brief, could disrupt markets, halt trading and lead to significant monetary losses.

The undersea battlefield

Given the strategic importance of undersea cables and the multifaceted risks they face, Western governments intent on preventing further conflict would be wise to find a comprehensive and internationally coordinated way to secure the infrastructure against threats.

One clear option would be to bolster repair and maintenance capacities. Currently, a significant vulnerability stems from the overreliance on Chinese repair ships. China’s robust maritime industry and state-supported investments in global telecommunications has contributed to the Asian nation taking a prominent position when it comes to cable repair ships.

The protection of undersea cables should not, I believe, be viewed as the responsibility of any single nation but as a collective priority for all nations reliant on this infrastructure. As such, international frameworks and agreements could facilitate information sharing, standardize security protocols and establish rapid response mechanisms in the event of a cable breach.

But such international efforts would be fighting against the tide. The incidents in Taiwan, the Baltic Sea and elsewhere come as great power competition intensifies between the U.S. and China.

China, in developing deep-water cable-cutting technology, may be sending a message of intent. Meanwhile, the Trump administration’s “America First” approach signals a shift that could complicate efforts to foster partnerships for the general global good.

The defense of undersea cables reflects the challenges of our hyperconnected world, requiring a balance of innovation, strategy and cooperation. But as nations including China and Russia seemingly test and probe this vital global infrastructure, it appears the systems underpinning the West’s prosperity and security could become one of its greatest vulnerabilities.

John Calabrese does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.