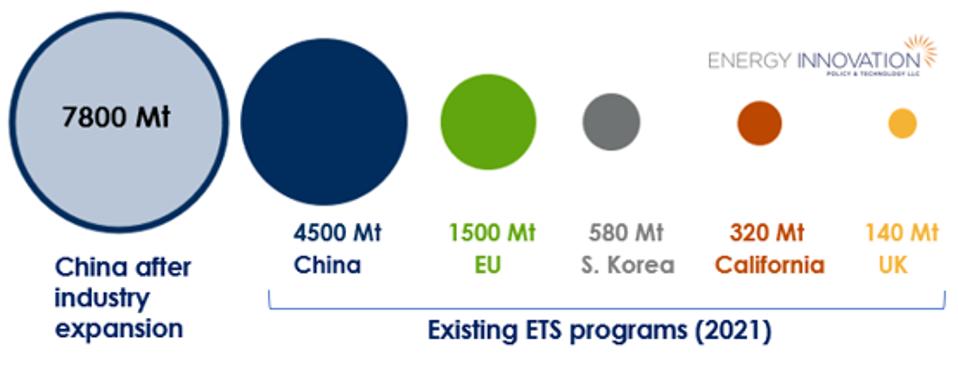

China’s new emissions trading system (ETS) is already the world’s largest carbon market, three times bigger than the European Union’s. And China’s ETS is about to grow 70 percent under plans to add heavy industry and manufacturing, making it the single largest global climate policy, covering more emissions than the rest of the world’s carbon markets put together.

As the world’s largest greenhouse gas emitter, the success or failure of China’s ETS will help determine the future of climate change. However, the timing of the program’s progression is uncertain, slowed by political and bureaucratic hurdles.

New research from Energy Innovation, IFS, and iGDP outlines how China’s ETS can successfully expand to spur domestic innovation, fuel economic growth, overcome implementation challenges, and achieve the country’s commitment to peak carbon emissions before 2030. These rising domestic benefits should increase momentum for expanding and strengthening China’ ETS, raising hopes for the sharp emissions reductions needed to head off dangerous climate change.

China’s carbon market became fully operational in 2021

China’s ETS became fully operational in 2021 when companies under the program were required to deposit emission permits with the government to account for a portion of their 2019 and 2020 emissions. The program initially regulated carbon emissions from power plants, covering about 2,200 energy producers.

The vision for China’s ETS has always been a much broader scope, covering more industries and emissions. When China announced a nationwide ETS in 2015, it envisioned the program covering, “a substantial percentage of China’s carbon pollution.” In 2016, early program design work proposed covering emissions from electric power generation and six additional industries: iron and steel, aluminum, cement, chemicals, papermaking, and civil aviation.

In 2021, the implementing agency, the Ministry of Ecology and Environment (MEE), introduced mandatory data reporting requirements for these additional sectors, which China’s ETS is expected to formally include by 2025. The chairman of the Shanghai Energy and Energy Exchange, which operates China’s national carbon trading platform, expects program expansion to happen in 2022 with inclusion of aluminum and cement before the end of this year.

Innovation benefits in growing markets

China’s policymakers are focused on boosting economic performance, raising the importance of China’s ETS to spur innovation through emission reduction requirements and establishing a carbon price, incentivizing low-carbon investments and products. As China’s ETS ramps up deployment and decarbonization solutions, it will drive learning by doing and scale benefits. In the marketplace, accelerated technological progress and economies of scale will yield better performance and lower costs for consumers.

These economic upsides create competitive advantages in clean technologies during a time of growing international demand. The International Finance Corporation estimates clean tech will be a $23 trillion opportunity in the coming decades. These growing economic opportunities are not just theoretical. Global investments in the technologies needed for carbon neutrality jumped 25 percent to $755 billion in 2021, up from an increase of about 10 percent in 2020, and building on two decades of solid growth.

Clean tech disruption is most obvious in the electricity sector where renewables have emerged as market leaders, capturing more investment than any other technology, but this trend is broadening to every economic sector. Consider the iron and steel industry, one of the sectors planned for inclusion under China’s ETS.

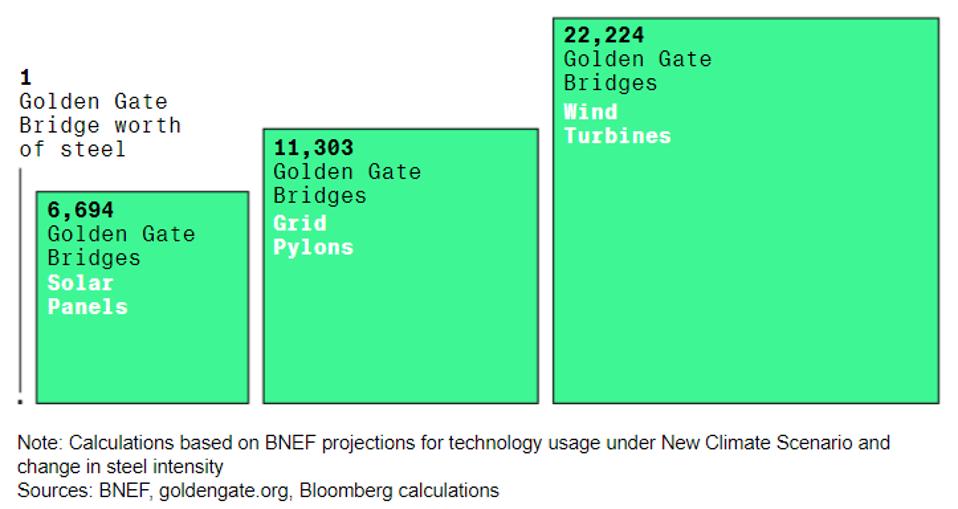

By 2050, Bloomberg New Energy Finance estimates the world will require about 1.7 billion tons of steel for wind turbine manufacturing—enough to build 22,224 Golden Gate Bridges. Manufacturing solar panels and electricity transmission line pylons will also be major consumers of steel, with demand estimated at 11,303 Golden Gate Bridges and 6,694 Golden Gate Bridges, respectively.

China’s steelmakers are well positioned to compete in an increasingly carbon constrained global economy. Baowu, the world’s largest steelmaker, has helped organize a global alliance committed to lower emissions. Baowu is pushing decarbonization technologies across its supply chain, increasing recycled steel and cleaner fuels, such as lower carbon hydrogen. Steel producers that get a head start on producing low-carbon steel can seize this economic opportunity, and the same will be true of other low-carbon energy and materials. Carbon pricing, or well-designed performance standards, can give countries and their companies an edge in these major future markets.

Roots of delay

Despite these growing economic upsides, questions about economic impacts and Chinese industry resistance have emerged as a barrier to expanding and strengthening China’s ETS, as indicated by the lack of an official timetable for industry expansion or milestones. The six sectors to be added under the China ETS include industries with greater exposure to international trade than electric power producers, introducing questions about whether compliance costs could damage international competitiveness.

But such international competitiveness impacts are modest, especially for China, given the size of its domestic market and influence of its enterprise in international markets. Yet China’s ETS design has gone all-out to avoid negative effects for covered enterprises, for example pursuing 100 percent free allocation, meaning it has distributed all tradable permits without charge. Despite this, industry opposition remains a hurdle to improving China’s ETS design.

How to maximize economic and climate benefits China’s ETS

Smart policy design features can alleviate economic concerns while maximizing economic opportunities, producing a tool better suited to helping China achieve its commitment to deep decarbonization.

Setting upper and lower limits on carbon prices, i.e., setting a price collar, is the simplest approach to cost containment and a recommended approach to address economic concerns while categorically ruling out carbon price spikes. The simplicity of a price collar offers communications and stakeholder management benefits compared to other more complex approaches to cost containment, such as the EU ETS’s Market Stability Reserve.

Two changes to China ETS design can maximize its economic advantage. First, broader industry coverage can extend carbon pricing benefits beyond the power sector. Second, consignment auctioning can overcome obstacles that have stood in the way of auctioning, enabling greater carbon market efficiencies.

Introducing auctioning — even at modest levels such as 2 percent to 5 percent of total permits available— will deliver a higher-quality price signal, lowering the transaction costs of deal-making, boosting carbon market liquidity. A pure free allocation approach, i.e., distributed tradable emissions permits without charge as China’s ETS has done, leads to inefficiencies, because it provides market participants less information about carbon price, increasing the transaction costs for permit trading, and suppressing market liquidity. Introducing consignment auctioning with revenue flowing back to covered industries will better meet the Chinese government’s goal of cost minimization.

Consignment auctioning solves a legal hitch, too – as MEE lacks legal authority for collecting revenue. Consignment auctioning allows for auction revenue to remain outside of government control, an approach taken by programs like the Western Climate Initiative linking California and Quebec, which uses a third-party platform to manage its auctions. China’s ETS could adopt such an arrangement, with a third party platform performing a monetary pass through service, returning auction revenue to firms consigning permits. By avoiding the need for the money to pass through government accounts, consignment auctioning can overcome a legal obstacle to auctioning.

Ultimately, the success or failure of China’s ETS hinges on whether it matures into a meaningful decarbonization driver. The clearest path to this goal is transitioning China’s ETS to a mass-based cap, setting a specific quantitative limit on the number of carbon allowances. The system’s initial intensity-based approach adjusts permit supply based on levels of industrial production. MEE took this approach in response to economic concerns, but the recommended price collar better serves this function. A mass-based approach better aligns policy design with China’s top climate goal, peaking its total greenhouse gas emissions before 2030.

A decisive decade for clean technologies

The latest climate science indicates emissions must decrease 43 percent by 2030 to be on track. As the world faces a decisive decade for investing in clean tech, China’s ETS must evolve. Since China is world’s largest greenhouse gas emitter, it is no exaggeration to say that the fate of future generations hangs in the balance.

This new research shines a light on the underrecognized and growing economic upsides for expanding and strengthening China’s ETS, which will induce faster technological progress and reduce costs as production ramps up. Such innovation and competitiveness advantages align with China’s national economic policy. Yet there is still no official timetable for industry expansion or other strengthening steps.

China has developed strong positions for leading clean technologies, including batteries, solar, and wind power, but no country has a lock on these still nascent markets. Many countries are interested in these fast-growing future pillar industries, including the United States, which led the world in electric vehicle exports as recently as 2019. While a window of opportunity exists for the U.S. and other clean tech contenders, they cannot count these major markets of the future remaining up for grabs indefinitely.

High-ranking Chinese officials recognize the opportunities presented by climate leadership. In a recent speech for example, Chinese President Xi Jinping said: “Coordination should be strengthened to take concerted moves in reducing carbon emissions, cutting pollution, expanding green efforts and promoting growth.”

Such sentiment suggests a renewed push to support the carbon market’s evolution, which could be enough to overcome policy and bureaucratic hurdles that have so far limited the impact of China’s ETS.