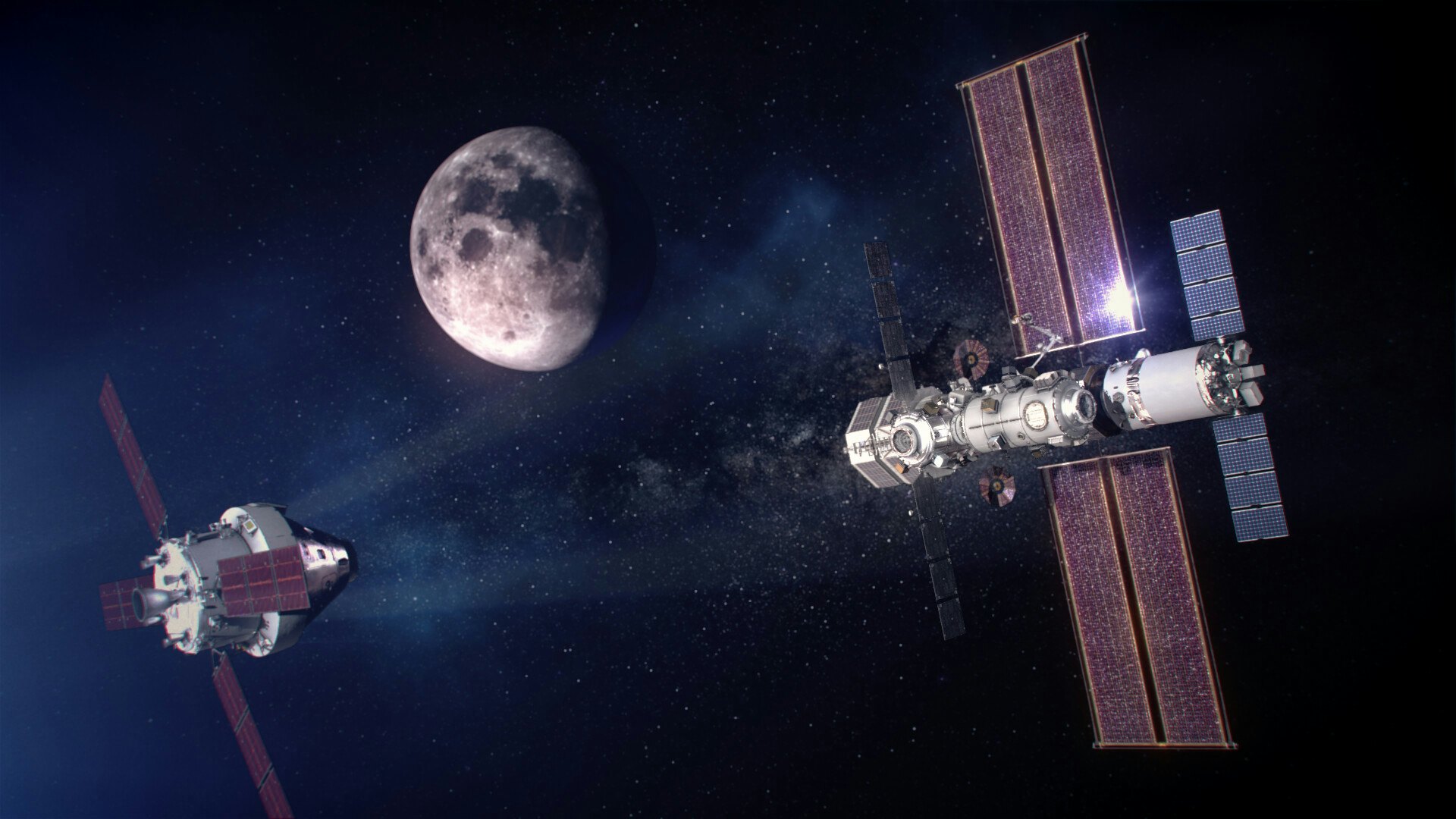

In the next decade, an international coalition plans to build a lunar research station to transform humanity’s exploration and observation of the Moon.

The planning phase is already underway, and it is going well. Construction is slated for 2026 through 2035, and crews could start operating from the base by 2036. The station will feature a lunar orbiter, a large, multi-level, habitat to enable surface-based activities, and play host to several lunar rovers.

If this sounds a lot like the NASA Lunar Gateway program, think again. The station, called the International Lunar Research Station, is a rival to the U.S. space agency’s plans to put humans permanently on the surface of the Moon within a similar time frame. Instead, the ILRS is the brainchild of China and Russia — two of the U.S.’ greatest rivals on Earth.

To the Moon…

In 2021, Russia and China laid out their roadmap for the station, detailing a timeline that features three main stages:

- 2021-2026: Reconnaissance, featuring three manned missions to the Moon by Russia and China.

- 2026-2035: Build, which will involve creating the autonomously operating station.

- 2036 onwards: Occupance, meaning crews can live and work at the station and use it as a stop on the way to other space-based mission destinations.

China and Russia plan to build five structures on the Moon’s surface. The first will be built for resource extraction to help power the rest of the station. The two countries also issued an invitation for international partners like Saudi Arabia, Thailand, and the European Space Agency to pitch into the effort.

In addition to being equipped to study the Moon’s geology, ILRS will be able to observe the Moon in great detail, collecting observations of our natural satellite’s topography, internal structure, geomorphology, and chemistry.

“If you could access that water and process it, it has all kinds of uses, including support water, hydrogen, and oxygen.”

While the cooperative memorandum signed by Russia and China in March of 2021 stated the station will be for “multidisciplinary research and multipurpose work,” one clear purpose is to study and exploit the Moon’s resources — particularly, water.

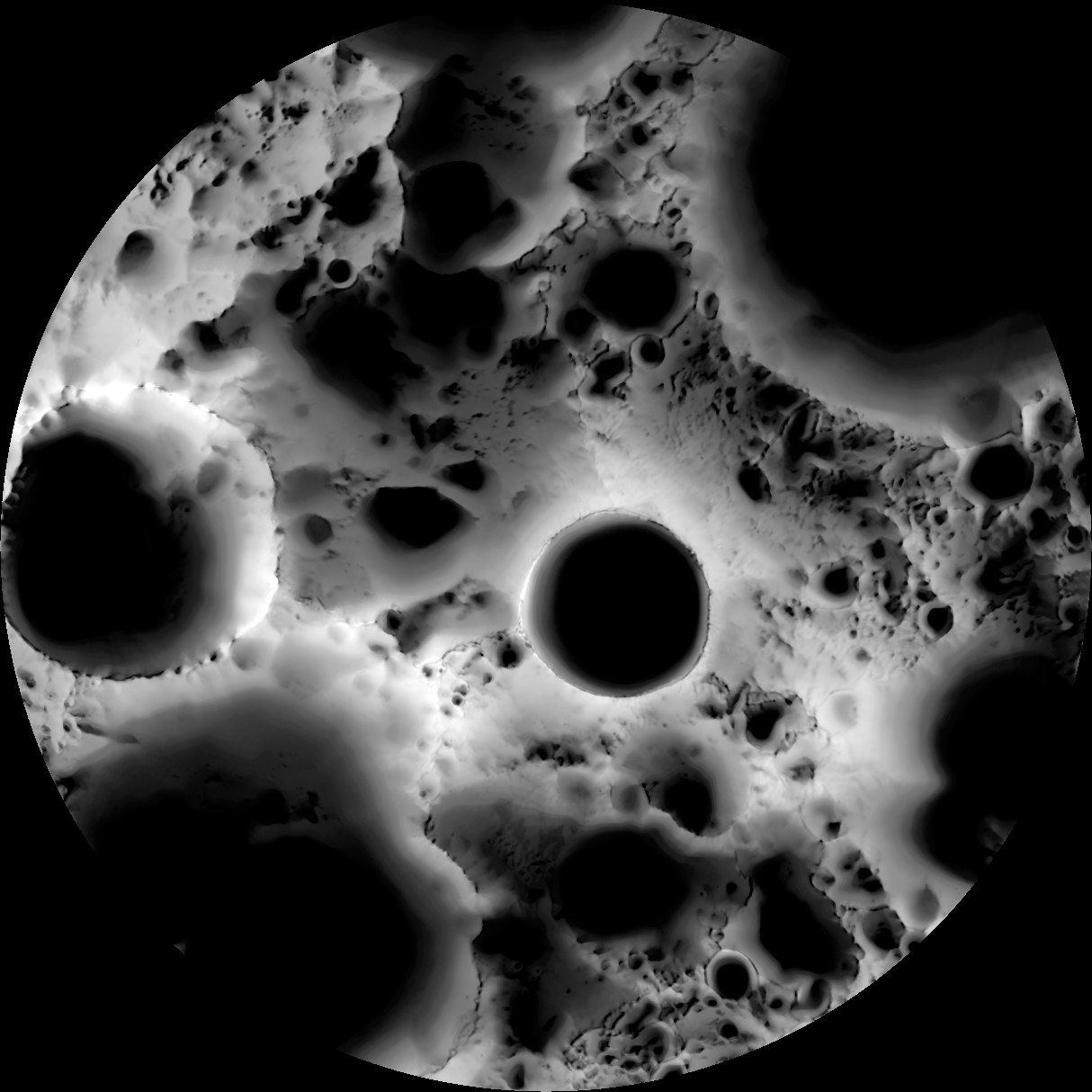

“There is the speculation that there is a valuable resource at the south pole of frozen water in craters that are never in sunlight,” says John Logsdon, Founder and Former Director of the Space Policy Institute at George Washington University and a former member of the NASA Advisory board.

“If you could access that water and process it, it has all kinds of uses, including support water, hydrogen, and oxygen. So, the oxygen can be used to support people over the Moon, the hydrogen can be used as rocket fuel,” he explains.

The next launch is on August 22, 2022: Russia is launching the Luna 25 mission to the Moon to land at the Moon’s south pole. There, it could join Yutu 2, a rover brought to the Moon in 2019 by China’s Chang’e 4 lander (which was also the first successful landing on the far side of the Moon).

Chang’e 4 contained potatoes, silkworms, and plant seeds to study how they might all survive the cold aphotic conditions. Meanwhile, Yutu 2 is currently exploring the Von Kármán crater. This large surface feature at the lunar south pole may contain subsurface water and could even yield crucial clues to the history of the Solar System.

But what about NASA?

Regardless of what these early ventures uncover, China is setting itself up to make a name for itself in space and ILRS is a loud answer to NASA’s Artemis program.

NASA’s Artemis program intends to send humans to the Moon for the first time since 1972. Right now, a crewed flight is planned to take off at some point after 2025, but that is subject to change due to delays affecting uncrewed precursor mission Artemis I.

Like China and Russia, the U.S. space agency has a greater ambition to establish a continuous human presence on Earth’s satellite planet by 2028. In addition to continuing space research, NASA hopes that the colony will help aid in the privatization of lunar exploration and the development of a lunar economy, though details of how this will come to pass are still largely nebulous.

2036: When China and Russia hope to open their lunar space station

NASA’s Lunar Gateway, the final stage of Artemis, is itself just one stage in a longer-term goal to send humans to Mars. According to NASA, a manned lunar station will, “serve as a gateway to deep space and the lunar service.” Its earliest components are set to be completed by 2024. If it goes ahead, the space station may become the most expensive space project ever, surpassing the ISS, which has cumulatively cost $100 billion so far.

Previously, the U.S. excluded China from participating in the ISS as part of the 2011 Wolf Amendment, which prohibits China from working with NASA on any joint agreement unless special approval is given by Congress. Since its inception 20 years ago, no Chinese national has ever spent time on the ISS, which is operated by five space agencies: NASA, Roscosmos, JAXA (Japan), ESA, and CSA (Canada).

This legislation may be what ultimately pushed CNSA to start building their own orbital space station, Tiangong (meaning ‘heavenly palace’ in English). The first module launched in 2021, and on April 16, 2022, a crew that spent six months on the Chinese station successfully returned to Earth.

But China wants to go beyond our orbit, it seems. In another parallel to NASA, it is going to the Moon, specifically, to the south pole.

Settling in the south

The reason why countries are interested in exploring the Moon’s south pole is that this region has icy craters. Officially discovered in August 2018 by a team of researchers using data from NASA’s Moon Mineralogy Mapper, the mission charted the reflective properties of lunar minerals, confirming the presence of solid water on the lunar surface.

The findings were detailed in a 2018 paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences by scientists Shuai Li, Richard Elphic, and their team.

As former NASA advisor Logsdon says, this discovery opens doors to future space research and industrialization: Lunar ice can be commodified. In this way, the ILRS station could become the first of its kind — a base to enable the exploitation of material from another body in space that would help serve future endeavors. Ultimately, it may mark the beginning of a new space industrialization race.

All the lunar rovers, landers, and space probes that have come before have solely collected information, doing reconnaissance on the Moon that allows scientists on Earth to better understand processes that lie beyond our reach to observe directly. But an autonomous lunar space station could enable a more industrial and practical future for space research and development.

On the horizon…

Ultimately, the space station will be the crown jewel in a growing relationship between Russia and China on and off Earth. The two countries already host monitoring stations for each other’s global positioning systems, GLONASS (Russia), and BeiDou (China). Last June, Putin confirmed the undeniable in an NBC interview, “We have been working and will continue to work with China, which applies to all kinds of programs, including exploring deep space.”

This is all coming to a head now with the ongoing invasion of Ukraine: In a febrile global political context, Russia’s interest in collaborating with NASA in any capacity has waned. In turn, Russia has moved closer to China, strengthening the pair’s ongoing scientific endeavors.

China has already come to Russia’s aid: In February of 2022, Dmitry Rogozin, the head of Russia’s space agency Roscosmos, said Western sanctions might affect spacecraft production because of the scarcity of microelectronics. But Rogozin pointed out at the time that Russia’s ties to China meant these problems would be short-lived. As the war continues, the divisions between NASA and its long-time collaborator Roscosmos may only widen. Logsdon suggests that this isn’t necessarily a surprise.

“The politics on Earth drive what happens in space,” he says.