Common perceptions about Chinese engagement in Africa are that it is one-dimensional and sometimes biased. One common problem with this perception is the seeming acceptance of what’s called ‘methodological nationalism’ – that the national origin of a firm or agency determines outcomes.

In her book The Specter of Global China, sociology professor Ching Kwan Lee points out that:

popular discourse and consciousness do not distinguish between state and private Chinese investors, who were all lumped together as ‘Chinese companies’.

Meanwhile, Africa, a continent with 54 officially recognised states, has often been portrayed as a fragile, vulnerable single entity that has been exploited by China.

In reality, neither the Chinese state nor Chinese businesses can be thought of as homogeneous. As professors Marcus Power, Giles Mohan and May Mullins have emphasised China–Africa relations and interactions are no longer entirely directed by the Chinese.

The way Chinese firms behave in foreign countries largely depends on their local improvisation and ability to bargain with host country states. This is particularly true in the least developing economies.

Despite rampant groundless scepticism, little concrete evidence is available to support or disprove critics. Many questions on investment, aid, employment, governance, companies, sector dynamics and security, among other topics, cannot be answered on the basis of rumours or rapid appraisals.

My PhD research focused on a comparison of the light manufacturing industry and the construction material industry in Ethiopia.

I argue that far from constituting a homogeneous and static group, Chinese private investments in Ethiopia are highly diverse, fluid and complex. Motives and determinants of these firms to invest in Ethiopia differ significantly. This is true both across sectors as well as within the same sector (or same market).

My research shows that there are two other important variables that explain variations. The first is the type of firm (in terms of scale, history and origin of investment). The second is the entrepreneur’s background. This includes family and educational background, business experience and guanxi (connections and relationships).

Context is also key. Both China’s and Ethiopia’s political economy conditions have, to a certain extent, contributed to ‘push’ and ‘pull’ Chinese private firms to invest in Ethiopia. This includes government policies and institutional context at national and sub-national levels.

My findings bring in new field-based evidence that challenges common perceptions. Examples include the supposedly dominant role of state-owned enterprises in Chinese investment in Ethiopia. The findings add evidence to a growing body of research that dismantles the assumption that national origin of investors determines outcomes.

In addition, Ethiopia’s case has profound implications for other African countries. It has, to a certain extent, my research refutes the assertion that African countries are passive or impotent when it comes to outward foreign direct investment. It demonstrates that a landlocked country with limited natural resources can achieve rapid industrialisation and economic growth through proactive industrial policies and committed government.

Common perceptions debunked

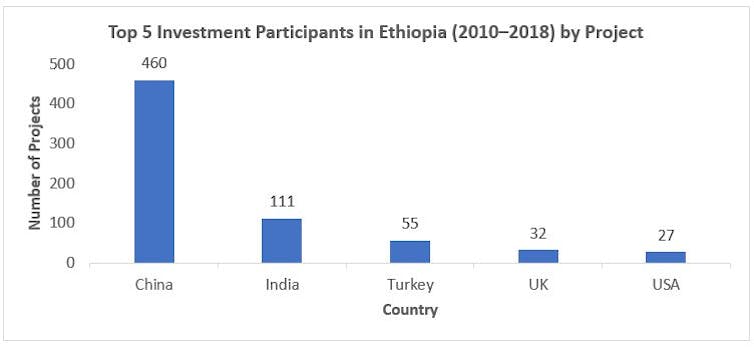

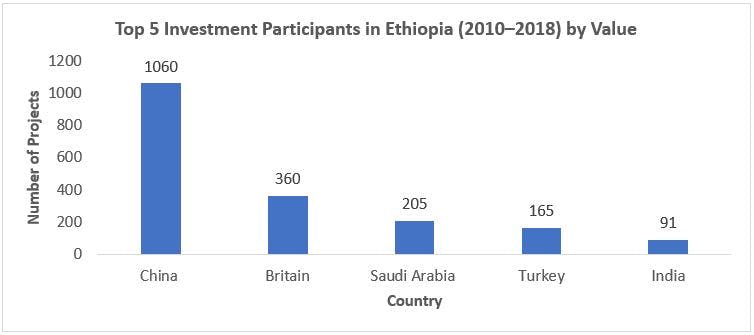

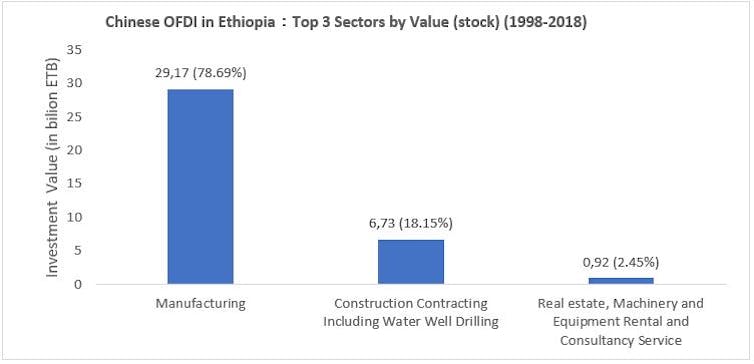

My research finds that the Chinese private sector plays a dominant role in manufacturing investment in Ethiopia. This is true by the number of projects and as well as by value.

For instance, investments (stock) (2010-2018) in the manufacturing sector reached ETB 29.17 billion (about US$570million). This accounted for 78.69% of total Chinese investment by value (see Figure3).

The construction sector does not feature prominently in foreign direct investment statistics in Ethiopia. This contrasts with the fact that Chinese construction firms are ubiquitous, especially in infrastructure projects. This is because these firms primarily engaged in the provision of construction services without necessarily creating greenfield investment.

For their part, Chinese state-owned enterprises are indeed playing a predominant role in the construction sector in Ethiopia. But this is mainly through project contracting rather than foreign direct investment.

This means that the private sector has been playing a large role in Chinese foreign direct investment in Ethiopia, mainly in the manufacturing industry. This challenges the common perception of Chinese engagement in Africa being dominated by state owned enterprises in mining and infrastructure construction sectors.

Instead of lumping all private firms into one category my study also identified different types of Chinese firms in Ethiopia. It also teased out their divergent motives and determinants, investment trajectories and the dynamic relations with the Chinese and Ethiopian governments.

It also found that Chinese private capital is not different from global private capital in terms of core motives to enter new markets. Evidence shows that profit-making and market-seeking are common interests for Chinese private firms. But they have distinct characteristics in comparison to global private firms. These include:

small to medium-sized family-owned firms that focus on the domestic market

traditional original equipment manufacturing that focus solely on the export market, and

owner-operated firms in the construction materials sectors.

Professor Yuenyuen Ang, author of How China Escaped the Poverty Trap, has argued that industrial transfer in China initially occurred domestically from wealthy coastal areas into poorer central and western provinces. In line with her argument, my study found that Chinese investment led by private firms in Ethiopia follows a specific sequence of events. Firms from coastal regions ‘go out’ first. Then those from inland China.

It also revealed that most private firms in Ethiopia are from specific coastal regions. These include Zhejiang, Jiangsu and Guangdong provinces. And that the firms have region-specific characteristics.

The drivers

Increasingly, Ethiopia has been seen as an emerging destination for light industry such as textile, apparel and footwear. It has attracted transnational suppliers from middle-income economies, such as China and India as well as global brands, mainly from the global north. Many have relocated their industrial capital there.

My findings showed that that the ‘going out’ strategies of Chinese firms were as a result of increasing costs. This included wage, environmental and late commercial payment costs.

Chinese firms have found that Ethiopia has reasonable productivity levels and, crucially, the potential for higher output. Their entry into Ethiopia was driven mainly by its proactive industrial policies and its committed political leadership which highlights the country’s comparative advantage. Major selling points include low water, electricity and wage costs, a large and young labour force and favourable access to the US and EU markets.

Ethiopia has also infused outward foreign direct investment strategically into its national development and structural transformation agenda.

Dynamic landscape

The nature of Chinese investment in Ethiopia is highly dynamic.

My research focused on Chinese private investment in Ethiopia between 2008 and 2018. But since the completion of my fieldwork in September 2018, significant changes have taken place – in Ethiopia and the world.

Chinese private investment in Ethiopia has been affected by several factors. These include:

the policies of the newly structured Prosperity Party under Dr Abiy Ahmed, which has been in power since 2019

an ongoing and escalating civil war between Tigray People’s Liberation Front and the federal government

increasingly tense Sino–US relations

The US’s termination of the trade agreement-the African Growth and Opportunity Act from Ethiopia on 1 January 2022

the outbreak of COVID-19.

This means that there have to concerted efforts to capture ongoing dynamics. The potential lack of resilience of the emerging sectors and new investors could derail the successful industrialisation process to which many Chinese firms have greatly contributed in Ethiopia.

Addressing economic and investment resilience remains a critical challenge.

Dr Weiwei Chen works in the Department of Development Studies at SOAS,University of London. She is affiliated with Royal African Society. Previously, Weiwei was affiliated with the Ethiopian Investment Commission (EIC) as the Chinese Investment Advisor between Oct 2017 and Sep 2018, and the UNU-WIDER as the PhD Fellow (2019).

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.