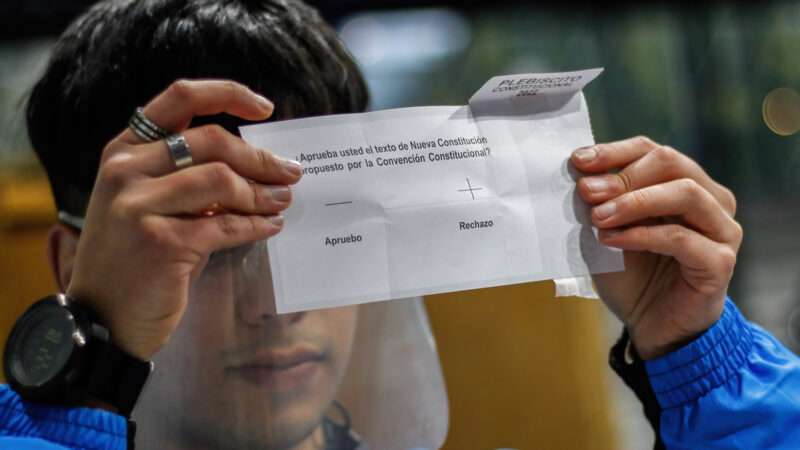

On Sunday, Chilean voters rejected a proposed constitution that an elected assembly had been drafting since 2021. The 54,000-word document would have replaced the free market–friendly 1980 constitution, banned "job insecurity," abolished the Senate, and massively expanded welfare programs.

Voting in the referendum was mandatory. Surveys conducted by Pulso Ciudadano in the months prior to the referendum projected the new constitution would fail, but no poll accurately predicted what turned out to be a 61.9 percent to 38.1 percent landslide rejection of the draft constitution.

President Gabriel Boric, who supported the document, says Sunday's rejection shows the efficiency of Chile's democratic system, and the government will try again to write a constitution that works for all Chileans.

"We have the opportunity to build the foundations of a new Chile," Boric said in a speech following the vote, "collecting the best in our history, embarking us on a journey that strengthens us as a country and as a community."

Enacted in 1980 during the military dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet, Chile's current constitution promoted the privatization of industry and social services. Through the amendment process, it helped lower inflation and poverty rates, cut red tape, and increase gross domestic product over the following 40 years. The country's free market economy has made it a model in the region.

But in 2011, student protests erupted over "unacceptable inequality," with protesters demanding economic and social change to address the gaps between the rich and poor. Leaders of the movement said the Pinochet-era constitution was largely to blame. In October 2020, a year after violent protests shook the country, 78 percent of Chilean voters opted to replace Chile's constitution.

The proposed replacement, drafted by a constitutional assembly elected in May 2021, would have permitted property and asset seizures by legislative decree, disbanded the Senate, ended school choice, mandated gender parity in all public institutions, and granted social rights that would expand the role of the state in health care, education, and housing.

It is true, as Boric stated in his speech, that the "vast majority" of Chileans want change. But it appears that voters were wary about the length of the document, its vagueness and breadth, and its numerous social proposals that seemed to go too far left.

"The constitution that was written now leans too far to one side and does not have the vision of all Chileans," one voter told the Associated Press.

Boric has made it clear that the process to change the country's constitution is not over. He said leaders must "work with more determination, more dialogue, more respect" to write another draft "that unites us as a country."

To that end, the 36-year-old has called on political leaders to come together to discuss how to move forward and to "agree as soon as possible on the deadlines and borders of a new constitutional process." On Monday, Boric met with Senate President Álvaro Elizalde, Chamber of Deputies President Raúl Soto, and leaders of different municipalities.

Elizalde and Soto are set to host meetings with Chile's political parties and social organizations, with Elizalde saying he hopes "to move quickly" to push the constitutional process forward.

The 1980 constitution has its flaws, for which it has been altered over the last four decades. "Yet," states a report by Niall Ferguson, a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution at Stanford Univesity, and Daniel Lansberg-Rodríguez, a constitutional research fellow at the Comparative Constitutions Project, "the idea that a constitution born in political sin can never become legitimate flies in the face of a great deal of history."

The practice of discarding constitutions and rewriting foundational texts in Latin America helps to explain the region's constant political turmoil.

An analysis by the University of Chicago Law School shows that the average lifespan of a constitution in Latin America is 12.4 years.

Ferguson and Lansberg-Rodríguez write that frequently replacing constitutions "can have precisely the opposite effect to what is ostensibly intended, weakening democratic institutions by denying them the benefits of reputations built up over time. By changing their constitutions too much too often, countries risk normalizing institutional vacuums, exacerbating instabilities and institutionalizing the kind of 'adhocracy' that constitutions are supposed to protect against."

Chileans have had three constitutions since 1833, and the 1980 constitution, while longstanding, has been heavily amended. Cuba has had four in the last 120 years.* Brazil has had seven since its independence in 1822. Venezuela has had 26. The Dominican Republic has had a whopping 38.

"A constitution provides legal stability and predictability—like a computer operating system," wrote Daniel Raisbeck, a policy analyst on Latin America at the Cato Institute, and I for Reason last month. "Tampering with any foundational code creates security holes that are easily exploited by political opportunists looking to amplify their own power and overturn the established order."

Whether voters will approve of whatever draft the government writes next remains to be seen. What is clear is that rehashing foundational documents, as Raisbeck warned, "could bring years of chaos, economic stagnation, and legal uncertainty."

*CORRECTION: Cuba has had four constitutions in the last 120 years.

The post Chile Rejects Constitution That Would Have Banned 'Job Insecurity' and Disbanded the Senate appeared first on Reason.com.