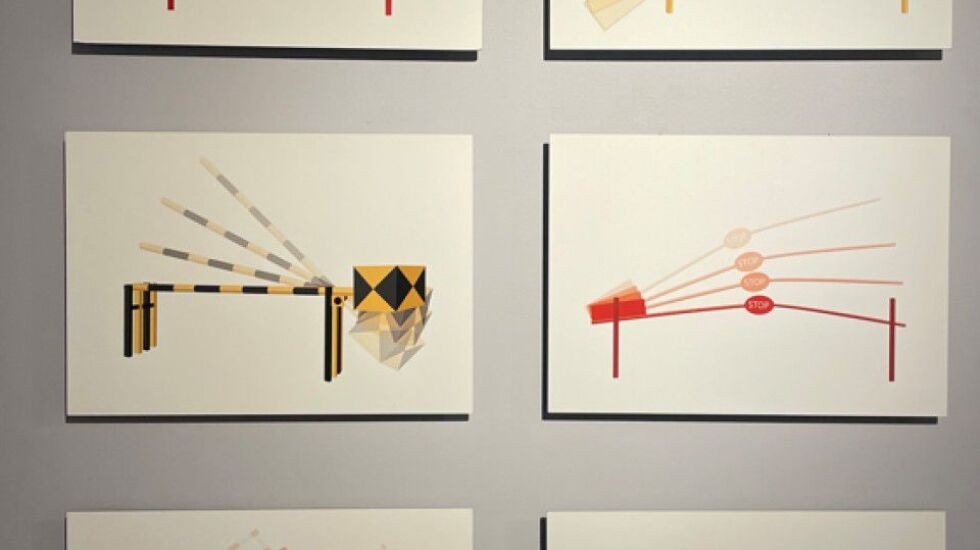

Captured in vibrant red and yellow against a white background, each barrier gives a distinct impression of movement.

The work reminded writer Dipika Mukherjee of her poem “Generations,” which starts with a poetic invocation to the goddess Durga, then weaves together the story of three generations of Bengali women — the multidimensional flailing barriers they encounter throughout life.

“Forging through one barrier often just leads to the next, yet we must persist, traversing borders and communities and transforming ourselves to make this world our own,” Mukherjee said. “We are armed with nothing more than a prayer to the goddesses we grow up with.”

“Generations” is one of 13 poems paired with a visual companion piece in “Testimonies on Paper: Art and Poetry of South Asian Women,” an exhibition that opened in January at the South Asia Institute and runs through June 10.

Poets were asked to choose from pieces of visual art pulled from the museum’s Hundal Collection and craft poems in response. All of the works feature South Asian women.

The artistic kinship between visual artists and poets is essential to “Testimonies.” Mukherjee likened the experience to touching someone through a mirror — a person you can’t quite grasp but whose presence you can feel.

Institute founder Shireen Ahmad said the idea came from a conversation about the lack of representation of women in the art world.

“Not only is it a problem with our mainstream artists, but then when you look at artists of color, and when you look at South Asian artists in particular, it’s even worse,” Ahmad said. “We hope that, with exhibitions like this, we can tackle that… one exhibition at a time and bring about a change.”

Curator Andrea Moratinos chose the visual pieces, which span generations and styles. Moratinos said she started with the basics — pulling works on paper by women artists.

“It was anything… that catches attention, like a deeper sense,” Moratinos said. “Honestly, all the works that they have in the collection are pretty great, so it was hard sometime.”

The art ranges from Abidi’s large, colorful barriers to a black-and-white depiction of the subcontinent done by artist Zarina titled “Atlas of My World IV,” in which the Radcliffe Line — the line of partition between India and Pakistan — stretches in black across the frame.

Many of the poems explore themes of gender, spirituality and migration.

“If you read some of the poems, you just get this sense of… this longing for what it was or when you used to live there… that sense of home,” Moratinos said.

Looking at the work of Abidi and Mukherjee, I felt a small fraction of kinship that the exhibition exudes. The description of the goddess in Mukherjee’s poem brings back moments of childhood, standing next to my mother, watching the rituals of Durga Puja. She did the same with her mother — my Didu — and I suddenly see us much like the generations in Mukherjee’s poem.

Despite the power and creativity that’s clear in the exhibition, Mukherjee said she feels stories of South Asian women often are tales of victimhood. She hopes visitors will find reasons in this exhibition to challenge that idea.

“The plenitude of artistic talent, of just the joy of creation, of just the magic of art and artistry that is inherent in the talent that is from South Asia is itself something very worthy to take back with them,” Mukherjee said. “This exhibition is a very clear answer to another window from which to view the Asian woman.”

I have long felt guilt and sadness that I can barely piece together a sentence in Bangla, a language so dear to the generations of women in my own past. But, as I move slowly through “Testimonies,” I am reminded of the parts of them I will always have, distantly linked memories of a goddess sinking into a river.