Eclectic, quirky, transporting and artsy. The Fine Arts Building is all that and more.

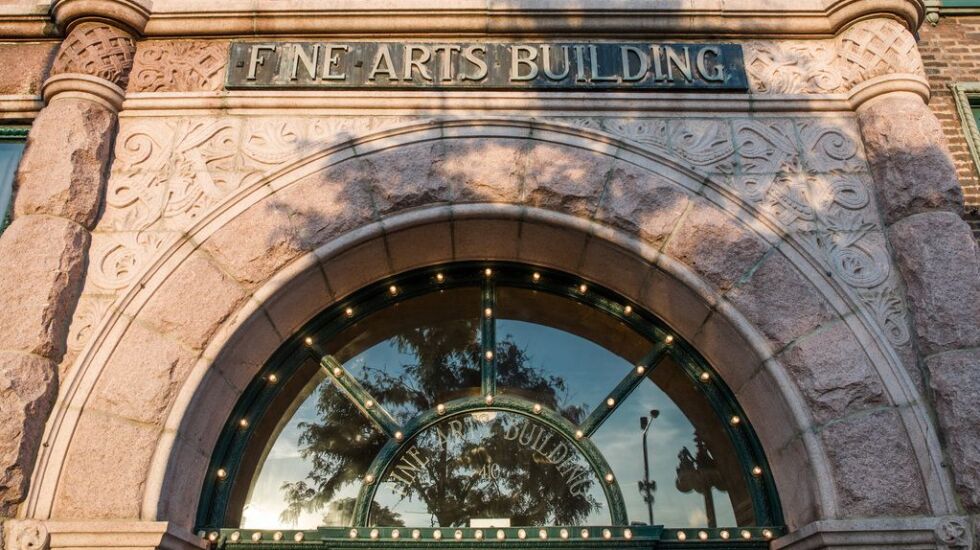

This venerable Michigan Avenue denizen, which sits across from Grant Park and between Van Buren Street and Ida B. Wells Drive, counts among Chicago’s most distinctive and most visited architectural gems.

The Fine Arts Building will celebrate its 125th anniversary with an open house and party from 5 to 9 p.m. Friday that includes a free concert by resident pianist Yulia Lipmanovich and other performances, gallery openings, artist demonstrations, refreshments and hands-on activities.

“It’s a pretty massive milestone,” said Jacob Harvey, the building’s managing artistic director. “There is just as much vibrancy of all arts sectors here as there ever was, so it calls for celebrating that.”

“Unique” is a tough word to apply to anything, because some conflicting example inevitably crops up. But it seems safe to use that descriptor in conjunction with the Fine Arts Building, because there is simply no other structure like it in the United States.

Certainly, historic, arts-focused buildings exist in other cities, like the Brill Building in New York City, famously associated in the past with the songwriting business, or the Gallery Building in San Francisco, which houses some two dozen commercial art galleries.

But neither of those structures can match the long history of the Fine Arts Building, and neither has its breadth of artistic activities, including dance, architecture, classical music, puppetry, jazz, photography and art.

Notable tenants have ranged from architect Frank Lloyd Wright, the groundbreaking Chicago Little Theatre and even the headquarters of the Illinois women’s suffrage movement in the past to the Chicago Human Rhythm Project and Chicago Youth Symphony Orchestras today.

“The importance of the Fine Arts Building,” said Tim Samuelson, the city of Chicago’s cultural historian emeritus, “is that it was and continues to be a place with a very diverse artistic community for many different disciplines, all working together, socializing and trading ideas, and basically, contributing to Chicago’s creativity.”

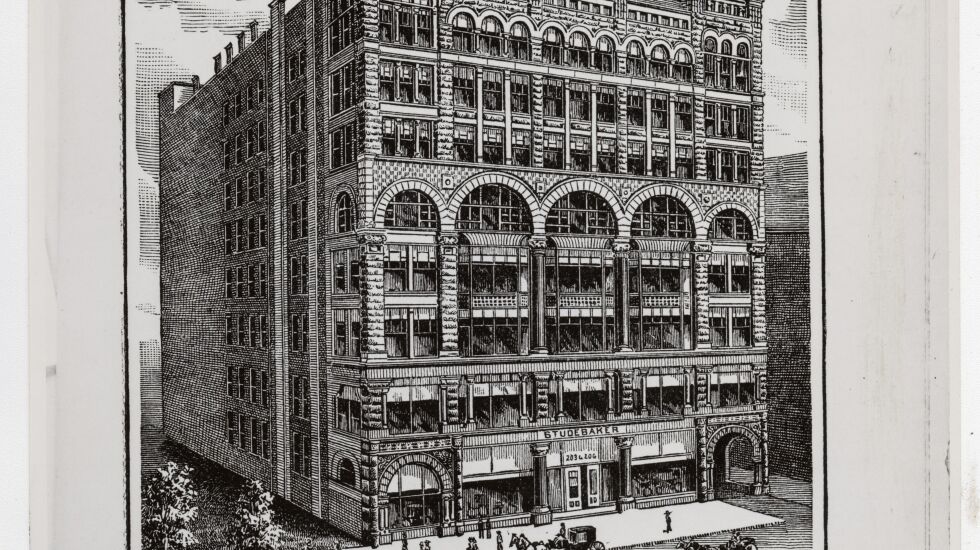

What became the Fine Arts Building opened in 1887 as a showroom and assembly plant for the Studebaker company, which, though later known for its automobiles, sold horse carriages at the time.

The building was an outlier because the other carriage dealers were along Wabash Avenue.

“They soon discovered that was a mistake,” Samuelson said. “They were off the beaten path of the carriage trade.”

So, a few years later, Studebaker built another, larger outpost just to the south on Wabash —a building now owned by Columbia College.

The question became what to do with the old structure, and Charles C. Curtiss, son of a former Chicago mayor and a well-known figure in the music business and cultural life of the city, suggested the idea for the Fine Arts Building and served as its first manager.

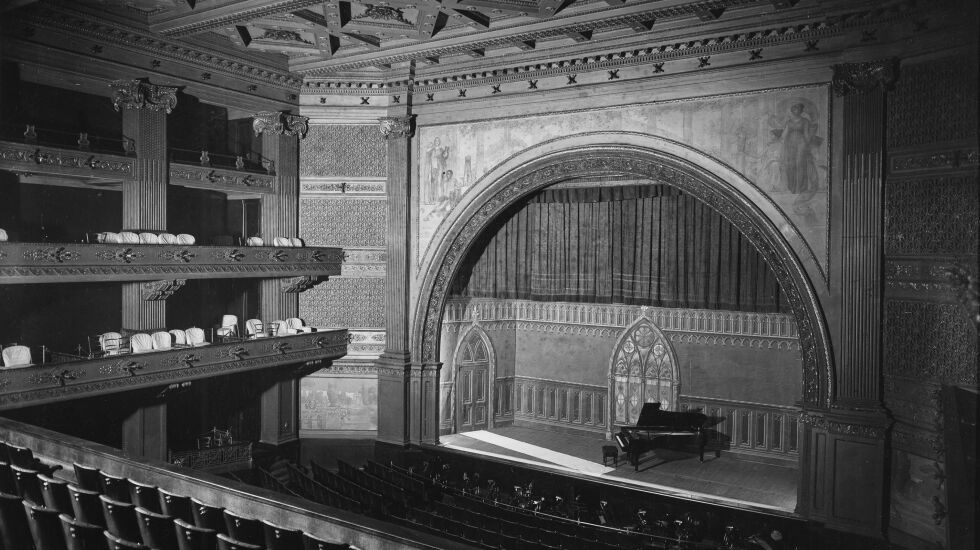

What had been essentially a warehouse was enlarged from eight floors to 10, with the facade modified to blend in the added floors, and refitted with two theaters, dozens of studios and other spaces and a courtyard. It reopened in 1898, serving a diverse roster of artistic tenants just as it does now.

The original building and overhaul were designed by Solon S. Beman, architect of the Pullman neighborhood, in the Richardsonian Romanesque style with dominant archways, massive columns and heavy, rusticated stone. What now serves as an annex to the Fine Arts Building on its north side was built in 1889 and refitted at the same time.

One of the building’s longest tenants is William Harris Lee III, who opened Williams Harris Lee & Co., his string instrument business in 1978, following on the heels of Bein & Fushi. His firm, which incorporates sales, rentals, fabrication and restoration, now occupies much of the fifth floor as well as a small space on the roof that is said to be a former speakeasy.

“I started here. We built our reputation here, and it’s been a home for us,” Lee said.

In all, there are a half-dozen such string instrument businesses in the building — the largest such assembly in the United States — catering to students, amateurs as well as Chicago Symphony Orchestra members and top musicians from across the country. A handful of other instrument dealers operate there as well, and Conn-Selmer, a major instrument manufacturer, plans to open an outlet in the building soon.

One of most striking aspects of the building, which was declared a Chicago landmark in 1978, is that its public interiors, including terrazzo floors, ornamental stair railings and 10th-floor art nouveau murals, have not been significantly altered or modernized. So a visit is really a trip back in time.

“When you walk into the building,” Samuelson said, “you know you are in a special place, and there is nothing else quite like it.”

Contributing to that feeling are the building’s venerable elevators, which are operated by Fine Arts staff. Because of the impossibility of getting parts for these holdouts from the past, the building announced in August that it will switch to automatic elevators in late 2024 or early 2025 while keeping as much of their original appearance as possible.

The Berger Realty Group acquired the building in 2005, and it has steadily tried to upgrade the building’s infrastructure and better highlight its story, placing archival plaques throughout and opening a pair of historical exhibits on the fifth floor.

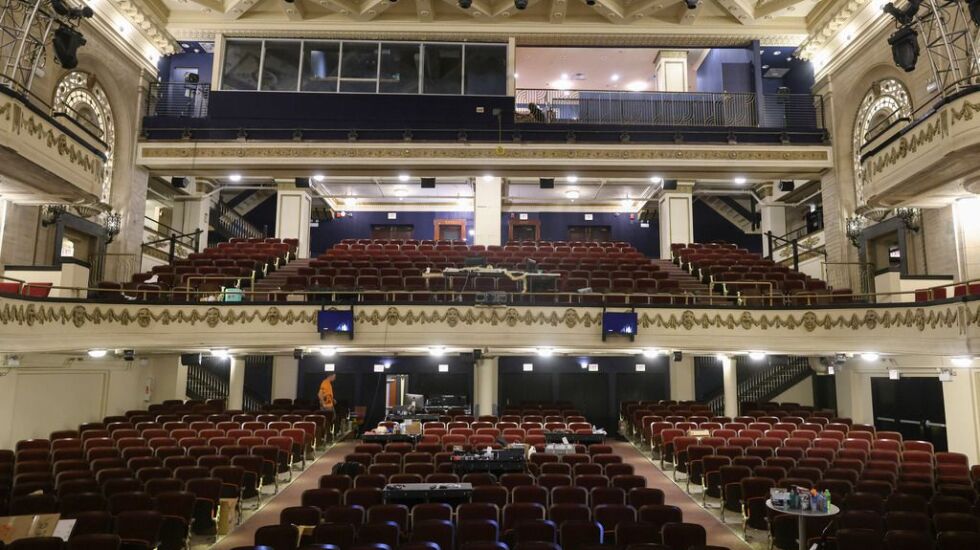

The Bergers’ biggest project has been a major renovation, restoration and upgrade of the 617-seat Studebaker Theater, including new seats and flooring and upgraded sound and lighting.

“The objective was a modern standard theater in a vintage jewel box,” Harvey said.

The theater is now the home of “Wait, Wait . . . Don’t Tell Me!” a weekly comedy news quiz show produced by National Public Radio and WBEZ Radio, as well as Chicago Opera Theater and the Chicago International Puppet Theater Festival.

Another well-known feature of the Fine Arts Building was the first-floor Artists Café, which closed in 2019 after 58 years of catering to celebrities and everyday customers. The space has been empty since, and the building management has made readying it for a new restaurant a priority.

For at least 50 years or more, there has been some kind of a bookstore off and on in the building, so when Exile in Bookville was looking for a physical space in 2021, it jumped at the chance to occupy a second-floor space that had served that role previously.

“Initially, we thought no way in hell, because it’s on the second floor,” said co-owner Kristin Enola Gilbert, “and who wants to be on the second floor? You want foot traffic. But then we started very quickly to think seriously how great it would be to have a bookstore in the Fine Arts Building.”

In addition to enjoying spectacular views, the store owners take advantage of the varied spaces in the building for its frequent author talks.

“Oh, it’s working out beyond our wildest dreams,” Gilbert said. “The building has been incredible.”