Seated outside her mud house in Burkapal, a tribal village in south Chhattisgarh’s Naxal-affected Sukma district, Markam Bime sums up half a decade of her life spent seeking justice for her incarcerated 50-year-old husband Markam Soma: “I visited the Jagdalpur jail a few times to meet him. Each meeting was just a phone call; neither of us could see each other. Conversations often did not last beyond an exchange of sobs. His only query was when he would be released. The only information I had was the next item that would be sold to secure his freedom.”

Nearly 10 km away lies Minpa, another tribal hamlet, where Podiyam Kosa, 30, is hacking the branches of a palm tree outside his house. He is attending to a task that has been pending for the last five years: building a thatched roof for the shed where his family stores forest produce. Kosa and his three brothers had spent those years languishing behind bars while their frail, old father managed the household and cared for the young children they had left behind.

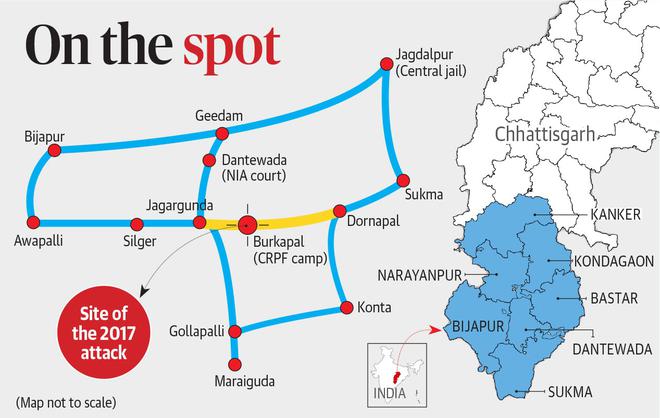

Mr. Soma and Mr. Kosa are among the 121 tribals who were acquitted by a National Investigation Agency (NIA) court in Dantewada on July 15 this year after the prosecution failed to establish their involvement in the killing of 25 Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) jawans in a 2017 Maoist ambush in Burkapal.

While the villagers finally received justice, their prolonged incarceration upended their lives and those of their dependants, who endured hardships to ensure that they walked free.

‘Massive 4 a.m. raid’

Burkapal is home to 39 of the 121 acquitted tribals, while the rest are residents of villages in Chhattisgarh’s Sukma and Bijapur districts, and Telangana’s Bhupalpally district. The residents of Burkapal say their ordeal began with a “massive 4 a.m. raid”. Thirty-year-old Kawasi Kosa says, “I was sleeping on a cot outside my hut when a large group of policemen gathered around me, waking me up. They dragged me away alleging that I was involved in the killings. I was taken to the Kotwali police station in Sukma, where I was repeatedly told to reveal the truth behind the attack. There was no such truth I was aware of.”

Madvi Lakshman, 32, and Madvi Sanna, 26, say they are the sons of Madvi Dula Ram, a former sarpanch of Burkapal who was allegedly gunned down by Maoists in 2016. A few months after the attack on the CRPF jawans, the police came and picked us up, they say.

The four brothers from Minpa say the police swooped on a wedding party they were attending in nearby Chintagufa and whisked them away.

When The Hindu visited Burkapal and Minpa villages, most of the interaction with the released men and their family members, who speak Gondi, took place with the help of Muchaki Nanda, 20, who acted as interpreter. Mr. Nanda says he studied Hindi till Class VIII, but was forced to quit school after his father was “framed” in the case in 2018.

He says the police picked up his father after an improvised explosive device went off in their field, injuring his mother. He maintains that his family still isn’t aware how the blast took place.

According to the FIR filed at the Chintagufa police station, at 12.55 p.m. on April 24, 2017, a group of 200-250 alleged Maoists fired bullets and hurled explosives at the 74th battalion of the paramilitary force in a three-hour-long gun battle, killing 24 jawans and an inspector-rank officer, and injuring seven others. The jawans, stationed at the Burkapal camp in south Sukma, were out providing protection for construction work on Dornapal-Jagargunda road.

A few Maoists were also killed when the security forces retaliated. This was the second deadliest Naxalite attack in terms of casualties in the region after the killing of 76 jawans in 2010 in the Tadmetla forest area of Dantewada.

The tribals who were rounded up were booked under various sections of the Indian Penal Code, Arms Act, Explosive Substances Act, Chhattisgarh Special Public Security Act and stringent provisions of the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA).

Markam Budra, 25, says the Chhattisgarh police and the CRPF jawans hung them upside down during interrogation before they were remanded in judicial custody and lodged in Jagdalpur jail.

Adapting to prison life

Getting used to life in prison wasn’t easy, says Kawasi Kosa. “The concept of time is loose for us. We wake up and sleep whenever we want. But in prison, we had to wake up at 4 a.m. and head for a session of yoga. Sharing a dark cell with over 100 inmates was in stark contrast to the lives we led under the open sky and in harmony with nature. We are used to indulgences like home-brewed toddy and hunting in the jungles with bows and arrows. But in jail, we had to follow a strict regimen. The portions of food served was fixed. Some days, there wasn’t enough dal, on others, they ran out of sabzi. Often, we had to go to sleep on an empty stomach. But who do you complain to about the quantity or taste of the food? We had to endure all this despite being blameless,” he says.

Convinced of his innocence, Mr. Budra says he felt he would be let off in a few days. “But as each day went by and the duration of my stay in jail grew longer, I slowly gave up all hope.”

Vetti Muka, 42, Mr. Budra’s distant relative who is also among those acquitted, says their ignorance about legal procedures left them at the mercy of lawyers at the NIA court in Jagdalpur, where the case was initially heard. The lawyers fleeced us after giving false assurances, he says. “When we met our lawyer on the court premises, he would charge a fee and promise to make sure we were free within a week. However, he would not turn up the next time we were produced in court. We would then be forced to sell more of our valuables to mobilise funds to hire a new lawyer.”

Debts start piling up

There was little progress in the case in the first three years, but debts started piling up, says Markam Bime. A visit to Jagdalpur jail would cost between ₹1,000 and ₹1,500 for two persons — a hefty sum “given our modest earnings”, she says. The trip would involve travel in a pickup truck to Dornapal and then a bus journey to Jagdalpur. They would then have to shell out more money for their food and accommodation there.

“When you are facing hard times and desperately want to sell your possessions to somehow tide over the crisis, people take advantage of your helplessness and use the opportunity to cheat you. That’s what happened to my family when they tried to urgently arrange money for my legal aid. A cow that would typically go for ₹13,000 fetched just ₹9,000. This was the case with all other items of property,” says Mr. Soma.

Thirty-five-year-old Madvi Dhurwa says his wife, Madvi Some, 30, was forced to leave their six-year-old son with relatives and migrate to Bhadrachalam in Telangana with their 10-year-old son to work in the chilli fields. “She had to do this because our family required funds to cover my legal expenses,” he says. From her daily wages of ₹200, Ms. Some spent ₹50 to buy a modest meal of rice and chutney for herself and her son. She saved the rest to support her husband’s fight for justice.

“We lead a largely self-sustaining lifestyle; money doesn’t play a big role in it. Produce from the forest, crops from our farms, and products from our livestock provide for our daily needs. We sell some of the produce to obtain money to buy clothes and medicines. Those who can afford a cell phone also spend some money to recharge their phones. Concepts like keeping aside savings and maintaining monthly budgets are alien to villagers. So, there was no question of anyone setting aside funds that could be used to pay for expenses such as legal fees and jail visits,” Mr. Dhurwa says.

His wife had to often tackle questions from their sons on their father’s whereabouts. “I tried to distract them by giving them biscuits, but that stopped working after a while. I couldn’t give them any assurance about when their father would return,” says Ms. Some.

Confined behind bars, the tribals could not perform the last rites of their loved ones. They also lost the opportunity to witness their children grow up. Kawasi Bheema missed his daughter’s wedding, while Madkam Hunga’s wife left him. Almost everyone had to part with their prized possessions to pursue their quest for justice and freedom.

Finally, a ray of hope

Muchaki Pandu, the sarpanch of Burkapal village, says the trial in the case started making progress in 2021 after the villagers approached Bichem Pondi and his associate, Bhima Podami, who had a reputation of taking up cases lodged against tribals. “Mr. Pondi speaks Gondi and other tribal languages, providing a certain level of comfort for the villagers,” says Mr. Pandu.

Mr. Pondi says all the lawyers the villagers had hired earlier had given them false assurances as it is almost impossible to secure bail in a UAPA case. “I presented a clear picture to the villagers. I told them the only way they were going to get out of jail was through an acquittal. When I checked the status of the case, I learnt that the charges had not been framed though the case had been registered three and a half years ago. The COVID-19 pandemic further hit their chances of securing an early release as the dates for hearings were being given after a gap of two-three months,” the lawyer says.

Mr. Pondi says the villagers had to face a linguistic barrier in their fight for justice. “All of them hail from the Gond tribe and Gondi is their mother tongue. But Hindi is the preferred language in court proceedings, while framing charges in the FIR and during interactions with lawyers. This left room for misinterpretation, which the prosecution took advantage of,” he says.

To address this issue, help to interrogate the tribals was sought from the personnel of the District Reserve Group in Bastar, a locally raised force conversant with the local languages and vested with the task of tackling Maoists. Yet, the villagers say, a lot of what they said was lost in translation and they often gave their consent to statements that they did not fully understand.

Mr. Pondi says his first task was to ensure that charges were framed in the case so that the trial could begin and the defence could examine the prosecution’s witnesses on whose testimonies the case largely stood. “There were 50 witnesses when the case entered the trial stage in August 2021. Apart from the witnesses’ statements, there was no corroborative evidence in the case, revealing that the police investigation did not meet the demands of a sensitive case. We cross-examined the witnesses and through our arguments convinced the court of the villagers’ innocence.”

Special Judge for NIA cases Deepak Kumar Deshlhre, in his order, said the court found no conclusive evidence against the villagers to prove that they had helped the Maoists in the attack. “No evidence or statements recorded by the prosecution was able to establish that the accused were members of the Naxal wing and were involved in the crime. No arms or ammunition seized by the police were proved to be found from the accused,” the order said.

Not an exception: Bela Bhatia

Bela Bhatia, a human rights lawyer based in Dantewada who was one of the defence lawyers, says the case may have garnered national attention due to the acquittal of a large number of accused. “This by no means is an exception; there is an underlying pattern. In many cases, people languish in jails for years before they are acquitted,” she says.

“To my knowledge, the Burkapal case had the largest number of accused arrested under the UAPA in the country. While 121 accused in a single NIA case is dramatic, it must be understood that around 200-275 similar cases with fewer number of accused have been disposed of and around 154 cases are still pending. At present, there are over 3,000 undertrials, many held under the UAPA, awaiting justice in Bastar’s jails.”

She explains some “genuine reasons” for the delay in settling such cases. “The judges and prosecutors are few and saddled with hundreds of cases. The complainant, the main witnesses and the investigating officers are often either the police or CRPF jawans. So, by the time the matter comes up for hearing, many officers are transferred and posted in other parts of the State or country.”

Ms. Bhatia says the Burkapal case saw arbitrary arrests and rejection of bail by the NIA court and the High Court. “Such factors along with no compensation after acquittal and no prosecution of police personnel for shoddy investigation and deliberate fabrication are common in most cases. They draw our attention to the problems plaguing the country’s criminal justice system today,” she says.

Case not yet closed, say police

Meanwhile, Sundarraj P., the Inspector General of Police (Bastar Range), says the case is not yet closed. “We are studying the court order and looking into lacunae in the prosecution’s arguments. Since the case fell due to witnesses turning hostile, the scope for appeal is limited. There are still other accused on the run and we are trying to arrest them.”

Another senior police officer says witnesses often turn hostile fearing backlash from the Maoists. He says Maoists allegedly killed three civilians in Sukma last month claiming they were police informers. “Can such a major attack be executed without local support? We never said all of them were hardcore Maoists, but villagers are certainly a part of their ecosystem. We did not arrest everyone in the village, we made the arrests based on certain inputs,” he says.

The police officer adds that it is hard to tell the difference between a Maoist and a villager. “The Maoists’ Battalion 1 comprises well-trained fighters with sophisticated weapons such as snipers, laser-guided bombs and assault rifles. Many villagers train with them in the dense forests and come back,” he says.

Ms. Bhatia says it is the prevalence of such theories that allows the police to implicate innocents in fabricated cases. “The chargesheet mentions 119 other accused and 100-150 ‘unknown Maoists’ on the run. The case, therefore, is far from over for the villagers,” she says.

‘Hope this doesn’t happen again’

Back in the village, Madvi Lakshman says the real culprits always manage to get away while the finger of suspicion points at them. “Innocent people like us have to bear the brunt of someone else’s actions. But what choice do we have? We can only reconcile ourselves to this situation and move on. I hope this doesn’t happen to us again,” he says.

Podiyam Kosa is still clueless about how he ended up in prison. “I had merely gone to attend a wedding and I was arrested. I hope my brothers and I are allowed to live in peace now.”

Markam Budra says he is relieved to be back with his family, but “there is still a lingering fear that the police might come again to take me back to jail”.

.jpg?w=600)