1984 through 1985 was quite a time for music. Rock, pop, rap and dance happily co-existed in the charts and big names could bank billions as big labels pumped cash into big egos. And there, at the tail end of ‘84 was Band Aid, a moment when all the riffing and rivalry, pomp and pouting was put aside and the UK’s biggest music celebs of the day banded cack-handedly on a funny little half-tune without a chorus. Oh, and raised £200 million (as the last count) for charity.

Needless to say, if an enraged singer in an ex-popular new wave band and a bunch of preening poseurs could muster such glory, imagine what could be done if the real professionals gave it a go…

While it’s easy to wave off USA For Africa and their charity singalong, We Are The World, as simply being ‘the American Band Aid’, it’s actually easier to count the differences between the two gatherings than the similarities.

The story of Band Aid and Do They Know It’s Christmas is a shuffling, shambolic, altogether British business that we’ve touched upon previously here. And, thanks to its unlikely, ‘ne’er-do-wells-do-well’ backstory, it now sits in the collective national past-consciousness as a rare moment in the ‘80s when the UK got it right.

By comparison, the organisation and creation of USA For Africa’s We Are The World - while following on Band Aid’s coat-tails and replicating its we’re-all-in-this-together formula - was a far more planned out, thought out and ultimately contrived affair.

With a new documentary, The Greatest Night In Pop, landing on Netflix on 29 January and telling the story of the making of We Are The World, here we take our own look back at how the whole thing came together.

Humble beginnings

Band Aid’s call to arms began with Bob Geldof famously bypassing any manager or agent and using his network of friends to cough up popstar’s numbers so that he could pressure them in person. The recording of Do They Know It’s Christmas had taken place on 25 November, 1984, and had seen most of the UK music scene’s biggest stars magically descend at SARM Studios, in Basing Street, London, make a record, make millions and enjoy a subsequent profile uplift that money couldn’t buy.

US mega managers had been blind-sided by Geldof pulling off the ego-ditching impossible across the pond, and began plotting how they could perform a similar profile-boosting operation Stateside, but once again it fell to one man being sufficiently outraged to do something about it that ultimately got their project off the ground.

The credit for We Are The World therefore lies not with high profile frontmen Lionel Richie and Michael Jackson, but with humble Harry Belafonte, the Day-O (Banana Boat) crooner-turned-civil rights activist who, while the American stars of the day watched on passively at the events unfolding in Ethiopia (or more accurately didn’t watch at all), decided to take action.

Inspired by Geldof’s one man crusade, Belafonte got in touch with manager and promoter Ken Kragen - then managing both Lionel Richie and Kenny Rogers - to ask what could be done. “We don’t have Black folks saving Black folks. That’s a problem,” he intoned.

The heavily connected Kragen knew who to call. Of course, Richie and Rogers would be on board, but who could write the song and run the show? Simple. It was time to call Quincy Jones.

Q-ing up

Jones was and is, of course, a legend – potentially being able to write, arrange and produce the record – but, by virtue of being red hot from Thriller (the biggest selling album of all time) could guarantee the appearance of Michael Jackson along with a host of other stars, too. Not least Greg Phillinganes on keyboards, John Robinson on drums, Louis Johnson on bass and Michael Boddicker and Toto’s David Paich on synths, all of whom had worked on Thriller and were effectively Jones’ house band at the time.

Also, Jones had put together an all-star choir before, calling in big names to help lift the finale of State of Independence for Donna Summer in 1982. That song featured a star cast of Lionel Richie, Dionne Warwick, Michael Jackson, Brenda Russell, Christopher Cross, Dyan Cannon, James Ingram, Kenny Loggins and Stevie Wonder on backing vocals. Getting the same crowd back together for We Are The World would therefore be a walk in the park.

Thus a two-pronged attack began. Jones and team would take care of the music, while Kragen and connections would guarantee that somebody would turn up to sing it.

With the clock ticking and Quincy Jones breathing down their neck - “We needed a demo of the song like yesterday” - it fell to Lionel Richie to break the back of the task.

On that first call Kragen and Richie suggested getting Stevie Wonder on board as a writer but Jones disagreed. Wonder was busy recording an album of his own at this point and Jones refused to disturb him, he instead volunteered Jackson for the role. “Michael would like nothing better than to sit around and write so those two [Jackson and Richie] took it on,” he writes in his autobiography, Q.

Soon, Jackon and Richie began passing back and forth ideas on cassette with Jackson sending over tapes of him humming potential ideas and Richie doing his best to interpret them. The pair would even get together at Jackson's house and listen to national anthems to get inspired. But, with the clock ticking and Jones breathing down their neck - “We needed a demo of the song like yesterday” - it fell to Richie to break the back of the task. Richie brought over a tape of the song’s We Are The World chorus and chords with Jackson’s ideas becoming the verses while both artists worked out the lyrics together.

Making the demo

Gathering at Lion Share Studios on Beverly Boulevard LA the following week, Michael Jackon, Lionel Richie, Quincy Jones and keyboard player Greg Phillinganes thrashed out the song in the company of Stevie Wonder in support. The following day the team, with John Robinson on drums and Louis Johnson on bass, laid down a demo, complete with guide vocals from Richie and Jackson.

We Are The World was taking shape at last and Jackson had one more brilliant idea to contribute. Given that the demo had come out so great why didn’t he and Richie sing lead vocal and everybody else could just sing background?

While grateful that the song now existed, Jones put his foot down. “That would have really gone over great. I could just see Bruce Springsteen and Tina Turner and Ray Charles and Diana Ross singing background…” he writes. “Forget it. But Michael was serious. I had to talk him out of it. He asked Lionel to try and convince me but 44 other divas-when-they-don’t-have-to-be, don’t play that shit.”

In fact the only change between the demo and the final recording became the alteration of a single line. Originally the lyric had been “There’s a chance we’re taking, we’re taking our own lives,” but to dodge the line’s suicidal undertow it became “There’s a choice we’re making, we’re saving our own lives.”

With the song effectively in the can, all they needed were some people to sing it.

What are you doing on the 28th?

However, getting a galaxy of US stars to convene at a single recording studio and give up their time for free would require far more careful planning than unwittingly picking up the phone to a bellowing Bob Geldof.

Geldof had been able to catch all of UK music’s great and good simultaneously hungover in central London on a Sunday morning. For Jones to get US music’s biggest stars into a single place and at one time he’d need a little help.

Thus, unlike Geldof’s under-the-radar, person-to-person call to arms, the cry for America’s avengers to assemble became a strictly business affair. Instead, it was the managers and the labels who herded the sheep, and while many artists came along for the cause, it was label machination - eager to replicate the profile uplift that the stars of the UK record had enjoyed - that really got them to the party.

With the Band Aid template obviously in place, the ‘what the hell this was’ and ‘what they could collectively achieve’ message quickly hit home. Stars began to verbally sign on the line, and with every big name domino that fell, so another would fall after it. Soon, the inevitable buzz meant that artists were phoning artists (“Are you doing it?”) and managers’ and agents’ little black books got opened as the impending photo opportunity (plus the small matter of saving lives) was realised. The only stumbling block was the where and when - sure, stars would love to take part, but any talk of a location, date or time would nix them in an instant.

With every big star having every day of their global masterplan mapped out it was quickly realised that the only hope of any kind of in-person co-op would have to be built around pre-existing commitments. Thus, attention zeroed in on 1985’s American Music Awards, scheduled to take place on 28 January 1985, where America’s biggest stars were already on the hook to back slap and promote. With all the big names in one place, Jones saw a chance to nuke them all with a single blast.

But first… Awards!

Thus the 1985 American Music Awards took place at the Shrine Auditorium, in downtown Los Angeles, California with every big name in attendance. The event saw Lionel Richie at the top of his game, not only hosting the event but also picking up six awards. And when the AMA’s drew to a close, 46 carefully selected stars took to their limos, and a procession of swanky cars began to make the 10.5 mile drive across LA to A&M Recording Studios in Hollywood in order to make a little history.

While the big names opted for the big cars, everyman-turned-rock star Bruce Springsteen drove his own pick-up from the AMAs, parking it in the Rite-Aid grocery store car park across the road and walking the rest of the way without a bodyguard.

Following the show, most of the chosen 46 had slipped out of their stage attire into something less formal for the ensuing session, and for those that hadn’t planned ahead, hastily produced We Are The World sweatshirts, branded with the enterprise’s just-minted official logo, were on hand to prevent anyone feeling overdressed.

So far so good. However, before a note was sung, Jones’ post-AMA recording session plan was already showing its cracks. Many stars didn’t even begin to leave the Shrine Auditorium until 10pm, but with the group chorus scheduled to be recorded first, nothing could happen until all 46 stars had arrived in the studio. Jones had correctly reasoned that if he did solos first, the big names wouldn’t stick around for the chorus. But soon the clock struck midnight… then one… then two before any recording actually began.

Arriving at the studio, the song’s stars were greeted by a sign Jones had placed there reading “Check your egos at the door,” and after platitudes and congratulations to the night's winners were dispensed, the group were handed their sheet music and lyrics and Jones prepared them for a warm up of that big chorus. Meanwhile the studio next door had been set up as a ‘green room’ for the many managers, agents and hangers-on who were encouraged to stay out of the way and let the magic happen unhindered.

Time for business. But first, a special guest appearance by Bob Geldof.

The mastermind behind Band Aid had, of course, been given an invite. And, eager to convey the seriousness of their task ahead, he wanted to make sure that the band got the message. Thus, he took more than a few minutes to wipe the smiles off everyone’s faces and intone his clanging chimes of doom with an anti-pep talk. Finally, with an eye aways on the clock, Jones had the stars file in and form a throng beneath and behind four Telefunken C12 microphones that engineer Humberto Gatica had strung high in the studio at around 2am.

With all obstacles now negotiated and thanks to peerless prep, the We Are The World singalong was nailed within an hour, and Jones could breathe his first sigh of relief. Buoyed by the occasion, Al Jareau led the still assembled throng in an impromptu singalong of Day Oh - a tribute to Harry Belafonte who was present as part of the ensemble.

Now for the callbacks.

Sha-lingay y’say?

Jackson had written an answer part for the choir to sing, echoing the main melody, coming in just after the song’s key change at four minutes in. Taking inspiration from the song’s African connections, he’d crafted nonsense lyrics to give what he thought was a flavour of the continent. The words went “Sha-la… Sha-lingay…” and Jackson sang the part to the throng so that they could get a feel for it.

However, there was a dissenting voice in their midst.

On hearing the proposed part, Bob Geldof once more stepped in. Having by this time actually been to Africa, the pasty Irishman was the hapless gathering’s expert on the place, and he pointed out that singing made up fake African nonsense on a record that was helping Africa would at best be disingenuous, and at worst perhaps a little insulting, too.

Jackson was taken aback. He and Jones had meticulously planned the arrangement and were itching to get the last of the choral parts in the can - at this point they hadn’t even begun to record the solo spots. Jones’ carefully regimented recording session began to crumble as the famous 46 each took sides on the authenticity of ‘sha-la, sha-lingay…’ and he bid the MTV crew to stop filming as the spat ensued.

Some sided with Jackson and Richie. After all, the song’s writers had a reputation for faux-African posing - Jackson’s “mama-say mama-sa” on Wanna Be Startin’ Somethin hadn’t ruffled any feathers and Richie’s inexplicable “jambo jumbo” accent transplant on All Night Long had become iconic. It was all made up - so what?

But others sided with Geldof, not least what Jones calls “the good old boy” country star contingent who had baulked at the idea of being caught on camera singing any kind of faux-Swahili from the outset.

There was only one thing for it. In the meleé, Stevie Wonder made a call to Nigeria to get a translation. Simple. And within minutes the answer came back. They would all sing “willi moing-gu” instead. And “sure enough the shit hit the fan” writes Jones in his autobiography… The suggestion proved to be the final straw for country star Waylon Jennings who, cornered into singing “willi moing-gu” in the wee small hours, chose to walk out of the session instead.

After a debate as to whether they even spoke Swahili in Ethiopia it was Ray Charles who broke the deadlock. “Say what? Willi what? Willi moing-gu my ass!,” he protested. “It’s three in the goddamn mornin’. Swahili shit? I can’t even sing in English no more!”

That was it. Instead, it was agreed that they’d simply sing “are the world” and “are the children”, directly echoing the main part, and after a few run-throughs the cameras were turned back on and the deed was done. Now, finally - after another round of whooping and back-slapping - for the solos…

Standing in the spotlight

Of the 46 stars in attendance only 21 had solo parts, and so 25 stars could now be discharged. But, instead of heading for the door, the cut-adrift backing vocalists instead began harvesting autographs from the other party members… Great idea! And soon the whole throng collapsed into the passing around of each other's sheet music, with more platitudes exchanged as everyone in the room ensured that everyone else had signed everything.

On the cusp of chaos and with an eye on the clock, Jones was forced into a major change of plan. Obviously, he had intended to take each of the 21 star soloists into the vocal booth and carefully massage a performance out of them - a step-by-step approach that had worked perfectly well for Band Aid, with the producers able to mute and solo and pick and choose who would sing what. However, with time now sailing past four AM, Jones feared mutiny and worse, walkout, if he were to do so.

On the cusp of chaos and with an eye on the clock, Quincy Jones was forced into a major change of plan.

Instead, he and Gatica quickly organised a forest of all the studio’s available C12s and had the group line up around them. They were going to do the whole song, live, artist after artist in a single take. Standing the throng in line, in a giant horseshoe, Jones encouraged each to simply lean into their nearest mic, sing their line and lean out. Not a big ask for the seasoned megastars in attendance and all in a day’s work for superstar producer Jones, but more than a little toe-curling for stars more used to letting the studio do the heavy lifting.

Jones had had arranger Tommy Bähler go out and get records by every one of the stars involved and, by listening to their range, work out who would best sing what. So, while Band Aid has seen a few hastily photocopied lyric sheets passed around and taped to mic stands, the USA For Africa gang were far more prepared. There was a predefined running order and each soloist had a full musical score with their part clearly marked.

It was all right there in black and white and beginning far left with Stevie Wonder and Lionel Richie, Jones rolled the tape.

While some celebs chose to learn their part and sing from memory, others would grip their sheet music, hanging onto every line, as if for the first time, every time. Daryl Hall, for example - sandwiched between Journey’s Steve Perry and Huey Lewis (sans News) - took multiple stabs at “It’s true we make a better day just you and me”, each requiring him to bear down on his sheet music take after take despite the fact that he was singing the same eleven words.

Five chances at greatness

Takes were done an entire verse at a time, each star singing their pair of lines with enough coverage across five takes to ensure that magic, for each of them, was caught in the can.

Jackson himself was spared performing his chorus in the flesh (Jones instead leaning on his guide vocal recorded earlier) though he did contribute his “when you're down and out, there seems no hope at all” line live in ensemble for the song’s bridge.

The only hiccups were caused by the ‘in the round’ recording setup. With the entire throng essentially mic’d up and live, each was instructed to be absolutely silent during each take, something which was beyond the boisterous Cyndi Lauper, with her cascades of rattling jewellery requiring polite intervention from Jones.

However, as morning broke, Jackson and Richie - with more than a little help from Jones - had pulled it off. Even Bob Dylan and Bruce Springsteen had found a home within the song, with Jones holding back Springsteen to add counterpoint grit to the choruses and a little mini choir of Diana Ross, Stevie Wonder and James Ingram to add some ad-lib fills throughout. Wonder even came back the following day for more counterpoint work alongside Springsteen’s parts, creating the trading of lines here that didn’t actually happen on the night.

Thus, the deed was done and with everything in place… there were still a few things missing. Or, to put it another way, how come Prince wasn’t there?

Paging Prince…

To be absolutely clear, Prince WAS invited. The artist - at that time known as Prince because that was his name - was riding high in early 1985. In fact, earlier that night. Purple Rain had picked up Favourite Pop/Rock album at the AMAs and Prince had been there in person to pick it up. And with an invite in the bag, the drive across LA would surely have been a formality.

Given that there was a strong but unspoken rivalry between them, Jones liked the idea of having Jackson and Prince together on one record - he thought the pair would give the track an attention-grabbing focal point.

Prince, however, had other ideas.

In Alan Light’s book Let’s Go Crazy Prince’s engineer Susan Rogers describes how a back and forth between the artist and Jones had ensued. “I was with Prince one day at his home studio, just the two of us,” says Rogers, “and he got a call from Quincy Jones asking him to come be part of We Are the World. I only can hear Prince’s side of the conversation - I was in the control room waiting - but he declined it. It was a long conversation, and Prince said, ‘Can I play guitar on it?’ And they said no, and he ultimately said, ‘OK, well, can I send Sheila?’ And he sent Sheila (E).”

Lisa Coleman (of Wendy & Lisa and part of Prince’s band for his AMAs appearance that night) recalls: “I don’t remember even knowing about We Are the World until that day, when everybody was talking about it backstage. Like, ‘We’ll see you tonight, right?’ And I was like, ‘What are they talking about?’”

“Prince was pissed,” offers Wendy Melvoin. “He was like, ‘I don’t want to see any of you there, you’re not allowed to go there.”

Seeing an opportunity quickly passing him and his artist by, Prince’s manager Bob Cavallo made a hasty call to Jones. “At the American Music Awards, he keeps telling me the only thing he’ll do is play guitar,” says Cavallo. “So I call Quincy, and he says, ‘I don’t need him to fucking play guitar!’ and he got angry.

With the two camps in deadlock, Cavallo devised a plan to save face. “I’m gonna say you’re sick - if you go out tonight and you’re seen, I can see the headlines: ‘Prince Parties While Rock Royalty Saves Millions’ or whatever the fuck they want to write,” he says in Light’s book. “You’ve got to stay home, ride it out, and be sick.

“The two biggest things on the planet tonight are this recording session and you, and everybody is going to want to know why that’s not one thing. So, take your awards and keep your ass in the hotel,” advised Prince’s saxophonist Eric Leeds that night. However, by 4am, still riding high after his best album win, Prince couldn’t contain himself, and after rolling up at popular club Carlos and Charlie’s at 4am, his bodyguard Big Larry became involved in an altercation and was arrested.

Result: The UPI wire service ran with a story of “quick-fisted bodyguards provided a violent counterpoint to a night of international camaraderie.” Ken Kragen was quoted as saying that “the effort would have been much more marketable with Prince’s participation.” And the Los Angeles Times suggested that Prince’s actions “led many to think of him as an arrogant jerk.”

With Prince as a no-show the lines set out for him by Jones and Bähler - “If you just believe there’s no way we can fall” directly following Jackson’s “when you're down and out, there seems no hope at all” - went to Huey Lewis instead.

But why not just turn up? Wendy Melvoin perhaps sums it up best. “Because he thinks he’s a badass and he wanted to look cool, and he felt like the song for We Are the World was horrible and he didn’t want to be around “all those muthafuckas.

“It was horrible. He had us go to Carlos and Charlie’s and have a fucking party. I remember it perfectly, thinking, ‘This is so wrong. This is so wrong.’ We were embarrassed. Everybody in the band was horrified. And that’s where it felt like there's something shifting here, where he’s getting nasty. The entitlement - it was almost like a kid with too much candy.”

Case closed.

So, what about Madonna?

So what about the other mega star elephant that wasn’t in the room? Where was Madonna?

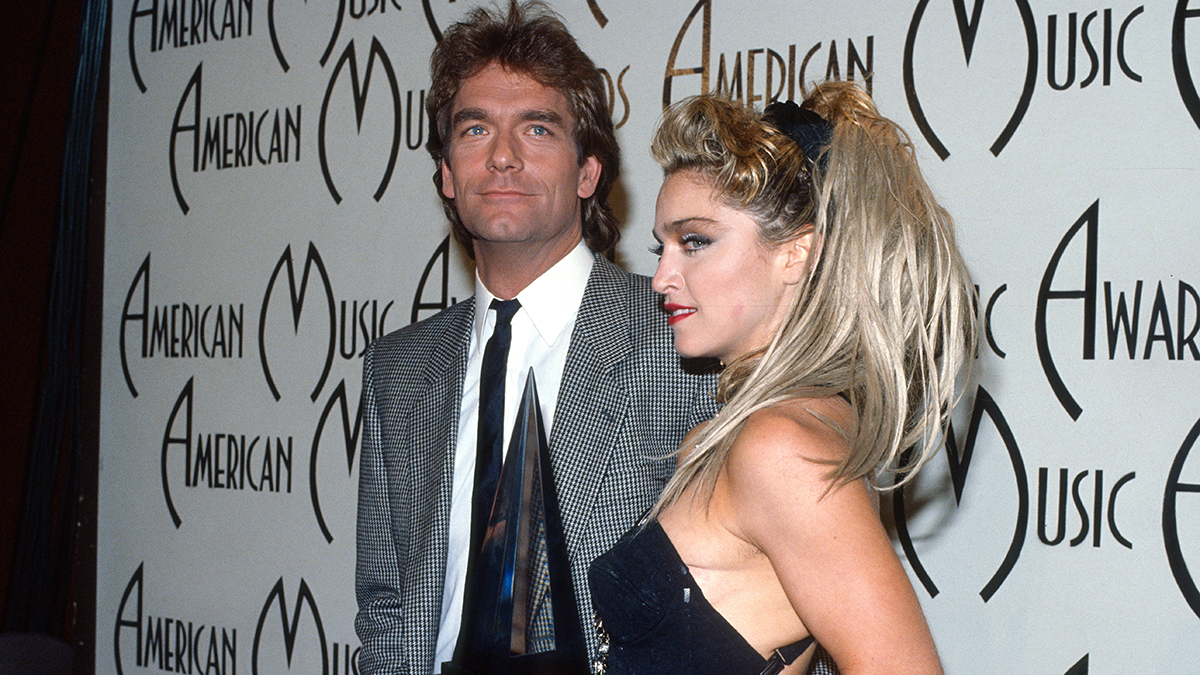

This one’s simpler - she wasn’t there because she wasn’t invited. At the time of the planning and recording she simply wasn’t - in the eyes of those organising the record - a big enough star to warrant a spot in the studio. But let’s take a closer look.

When We Are The World was recorded on 28 January, 1985, singles Holiday, Lucky Star and Borderline from her self-titled first album had all been hits (US chart positions 16, 4 and 10). On 14 September, 1984, Madonna had appeared at the inaugural MTV Video Music Awards with second album opener Like A Virgin - an appearance that arguably made her a star. But a big enough star for We Are The World four months later? Apparently not.

Most damning of all, though, Like A Virgin went on to hit the number one spot in the US Billboard charts on 22 December 1984 and stayed there until 2 February. Meaning that, on the night that We Are The World was recorded, Madonna was number one. And had been for five weeks.

Popular history has it that Madonna had a clash of commitments that night, being out on the road on her first major tour. But the Virgin Tour (with Beastie Boys in support) actually kicked off on 10 April 1985. In truth, she was right there in town too, having just hours earlier lost out to Cyndi Lauper in the Favourite Pop/Rock Female Artist category at the self same AMAs everyone else had just attended. (She can fleetingly be seen applauding Loretta Lyn picking up her Award of Merit here.)

And is it just us, or does Quincy Jones look surprised to find Madonna is even a nominee as he announces the winner? Ouch.

So, why no Madonna? Because she wasn’t asked, and being the pro she is, she didn’t ask to be included and has never commented on the matter to this day. But it’s quite possible that had the American Music Awards and the recording of WATW taken place just two short weeks later, the penny may have dropped and Madonna’s worth and future potential may have registered and she would have been standing in the Cyndi Lauper slot at both gatherings instead.

Oh, and it’s worth pointing out which record binned off We Are The World when it ended its four-week run at the top of the US chart in May 1985. That’s right, Crazy for You by Madonna.

Um… Dan Ackroyd is in reception…

So no Madonna, but we did get Dan Ackroyd. Wait a sec. How come Dan Ackroyd is on We Are The World? “Totally by accident,” he explained to New Hampshire magazine in 2010.

“My father and I were interviewing business managers in LA and we walked into this office of a talent manager, and realised we were in the wrong place. I was looking for a money manager, not a talent manager. I had managed myself at that time and always have. But he said, ‘so long as you are here, would you like to come and join this We are the World thing’. I thought, ‘how do I fit in here?’ Well, we did sell a few million records with the Blues Brothers and in my other persona I am a musician, so I showed up and was a part of it but it was totally by accident.”

Mystery solved.

A happy ending?

For all it’s questionable qualities - Cyndi Lauper has since gone on record as saying that everyone “thought it sounded like a Pepsi commercial” - We Are The World remains Quincy Jones’ biggest-selling record and one which - combined with sales of the spin-off album - has, at the last count, made $144 million for charity and prompted the US government to contribute around $800 million more for the same cause.

Trouble-making press at the time tried to make an issue out of the fact that MTV had hired in a Panavision lens for the occasion, using it to shoot Jackson’s solo vocal take for the first chorus to lend his sequinned socks and gloves and gold brocade tunic some extra sparkle. At a cost of thousands of dollars for this single shot, it was argued that the money would surely have been better spent contributing to the cause.

But, ultimately, the song would win three Grammy Awards in 1986, including song and record of the year. "A great song lasts for eternity," says Jones. "I guarantee you that if you travel anywhere on the planet today and start humming the first few bars of that tune, people will immediately know that song."

And when asked about the various naysayers on the project, Jones replies in Q: “Anybody who wants to throw stones at something like this can get up off his or her butt and get busy. Lord knows, there’s plenty more to be done.”