Midge Laurin dropped a check in a U.S. Postal Service mailbox on Central Avenue near her Southwest Side home in September — a $30 contribution to her cousin’s daughter’s school in Crystal Lake.

Three days later, she and her husband logged onto their bank account and found the check had been stolen, rewritten and cashed to a “Crystal E. Hunter” for $9,475.81.

“I couldn’t believe it,” said Laurin, a retired office manager. “How did they know I even had the money?”

Laurin’s husband, Francis, called Chicago police but was referred to the U.S. Postal Inspection Service, where he filed a report.

The couple visited their bank and were told it could take up to six months to recover the money. A bank employee told them seven other customers were recent victims of the same crime.

“They looked at us as if it was an everyday occurrence,” Laurin said.

The stolen check scheme, called “check washing,” exploded during the pandemic, leaving many victims struggling for months to recover their money. And it’s gotten worse in the last year, experts said.

In most cases, thieves steal checks from mailboxes and erase the ink using household chemicals. They then rewrite the check to a different person and cash it at an ATM or currency exchange.

“We are senior citizens on a fixed income and never expected this to happen,” Laurin said. She and her husband need the money for expenses related to their pending home sale. For now, that’s on hold.

“They said six months. That’s an awful long time to wait,” she said.

After a reporter reached out to Laurin’s bank, the bank told her the claim was settled and she could expect to be reimbursed in a few days.

The check-washing scheme has also hit people in power, including Laurin’s 13th Ward alderperson, Marty Quinn.

“I was totally blindsided,” said Quinn, who said he was unaware of check washing until last year, when he became a victim.

He said he learned he’d been scammed when he received a delinquent mortgage notice after mailing a check at a mailbox near 59th Street and Nashville Avenue.

“You hit the panic button because your identity has been compromised,” Quinn said.

Thieves are ‘hitting a jackpot’

Some stolen checks are sold on the internet for hundreds of dollars in what has become a “very organized type of crime,” according to David Maimon, associate professor of criminal justice and criminology at Georgia State University.

Money from the checks has been used to fund street gangs and buy drugs, guns, jewelry and cars, said Maimon, who leads the Evidence-Based Cybersecurity Research Group at the university.

His group monitors more than 60 underground websites to track stolen checks for sale, and it found more than 1,000 checks from victims in Illinois for sale on the dark web from December through May.

Check thieves have hit other states harder, Maimon said, “but we know things are picking up in Chicago.”

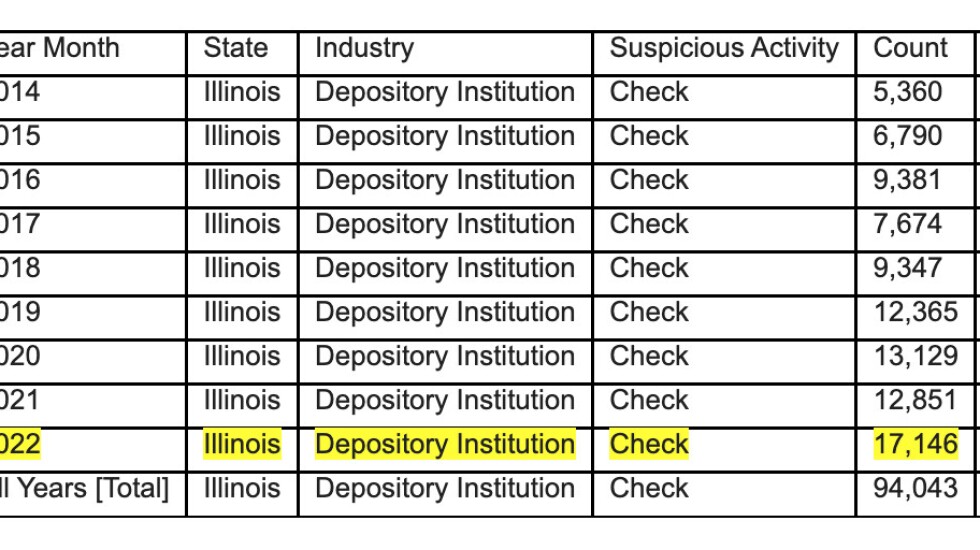

Although no agency could provide statistics related to check washing, all cases of check fraud have been rising steadily in Illinois, more than doubling from five years ago.

So far this year, more than 17,000 cases of check fraud have been reported in Illinois — compared to 13,000 cases in all of 2021, and 5,360 cases in 2014, according to the U.S. Treasury Department.

Why is this seemingly old-fashioned crime surging in an internet era rampant with its own host of virtual scams?

“It works. It means they’re hitting a jackpot, and people are telling their friends,” said Steve Bernas, president and CEO of the Better Business Bureau of Chicago and Northern Illinois.

How to avoid being a victim

Bernas offered these tips to avoid becoming a victim of check washing:

- Use a pen with indelible black gel ink that can’t be erased.

- Deposit mail with checks inside the post office, not in outdoor blue mailboxes.

- Pay your bills online.

- Grab incoming mail right away.

- Deposit mail with checks just before a mailbox’s last pickup.

Some victims wait months for reimbursement while their banks investigate the claims and work out among themselves who’s liable to pay, Bernas said.

The U.S. Postal Inspection Service declined to share statistics about check washing, armed robberies of letter carriers or the measures they are taking to combat the crimes.

“I can tell you we’re aware, anecdotally, of the trend,” said Spencer Block, a spokesman for the agency’s Chicago office. The Postal Inspection Service has been working with local police departments to combat check washing, he said.

Victims can report the crime to the Postal Inspection Service at (877) 876-2455.

‘Mind-boggling to see how things have progressed’

Maimon’s research team first noticed a resurgence of the stolen-check scheme in late 2021. Checks from Florida started showing up on the dark web, then New York, New Jersey and Philadelphia. Criminals following the same playbook then began stealing and selling checks in other towns across the country, including Chicago.

What typically happens is criminals rob letter carriers for their master keys, which can open mailboxes on the street and in building lobbies within an entire ZIP code. Keys are sold online for $800 to $2,500, depending on how lucrative a ZIP code is, Maimon said.

An uptick in stolen checks was linked to a significant increase in armed robberies of USPS letter carriers for their master keys, according to a March memo from the Postal Inspection Service to the Justice Department.

The Postal Inspection Service issues rewards of $25,000 for tips leading to a conviction for robberies of letter carriers. Robbers have been sought in at least four Chicago-area letter carrier robberies in the last year, according to wanted posters shared by the Postal Inspection Service.

At least five armed robberies of mail carriers’ master keys have been reported on the North and West sides since August, according to Chicago police.

Two letter carriers in Evanston were robbed at gunpoint of their master keys in a 24-hour span in September, police said.

Mack Julion, president of the National Association of Letter Carriers Chicago, told the Chicago Sun-Times that some carriers are considering not going out on their assignments.

“In any instance where they don’t feel safe, they certainly have the right not to deliver,” Julion said.

Maimon said the master keys are used to burglarize USPS mailboxes overnight.

A mail thief used a USPS key to steal mail from the blue box outside suburban Norridge’s town hall in August, police said. More than 40 checks were reported stolen this year in the village.

Criminals then chauffeur the stolen mail to hideouts — usually cheap hotel rooms — to sort the mail, Maimon said.

Some criminals have even hired drug addicts with the promise of food or cash to sift through the mail, Maimon said. They organize the mail into personal checks (which sell for around $125 on the dark web) and business checks (which typically sell for $250).

“It’s kind of mind-boggling to see how things have progressed,” Maimon said.

All types of people buy stolen checks online.

“There’s no one profile that we can identify,” Maimon said. “There’s a very extensive supply chain.”

The crime has become more complex in the last few months, Maimon said. Some criminals now offer personal information about their victims, including Social Security numbers and account balances.

In some cases, criminals use that personal information to take over bank accounts and create fake driver’s licenses and passports, which they use to open new bank accounts and credit lines.

“It’s really disturbing at this point,” Maimon said.

He said some criminals have sources in banks and credit bureaus who provide them information.

“The operation is completely synced and organized. These are not a bunch of youth stealing mail and washing checks,” Maimon said.

Little Italy a hot spot for stolen checks

Several recent victims in Chicago live in the Little Italy neighborhood.

“It’s super frustrating,” resident Liz Gardner said. In April, she wrote a several-thousand-dollar check to the IRS and slipped the envelope into a blue mailbox at Taylor and Loomis streets.

Two days later, her husband noticed their bank account listed the check as cashed by someone else. A copy of the check showed it was endorsed by someone else but the amount was unchanged.

She immediately told the bank and police about the theft but still hasn’t been reimbursed for the check.

“We’re now five months out and still haven’t recovered the money,” she said.

Another victim, Monica Pascente, mailed a $123 check for a credit card payment in August. Someone stole the check and cashed it for $9,500.

Pascente, who has lived on Taylor Street her whole life, said: “I feel that, as a U.S. citizen, anyone should be allowed to drop mail in mailboxes.”

She still mails her checks, despite knowing the risk.

“Not everyone is computer savvy,” Pascente said.

Kevin Ngo rarely mails checks, but he said he felt it was the right thing to do in June when he attended a wedding in New York but didn’t want to travel with a gift.

Sending the money by Venmo would have felt impersonal, he said.

The 33-year-old Little Italy resident dropped the $200 check in a mailbox at Laflin and Flournoy streets. A couple of days later, he got an email from his bank saying it wouldn’t cash his check written for $4,900.

His check had been stolen and washed. He filed a report with police.

“Ultimately, I was lucky, but I’m sad for everyone else who lost money,” Ngo said. “I’m not dropping checks in the mail anymore.”