GLENDALE, Ariz. — On his second day in the United States, Charlie Montoyo, then 17, got lost for three hours in San Jose, California, after looking for food, saddled with the reality of not speaking a word of English and with cellphones not yet in existence.

Learning English wasn’t just one of the conditions of the scholarship program that brought Montoyo from his native Puerto Rico — it was essential for him and the other Latin American prospects in the program to survive on the baseball field and in the real world.

“I relate pretty good to all the kids who come to the States and don’t speak English,” Montoyo said. “I know it’s not easy.”

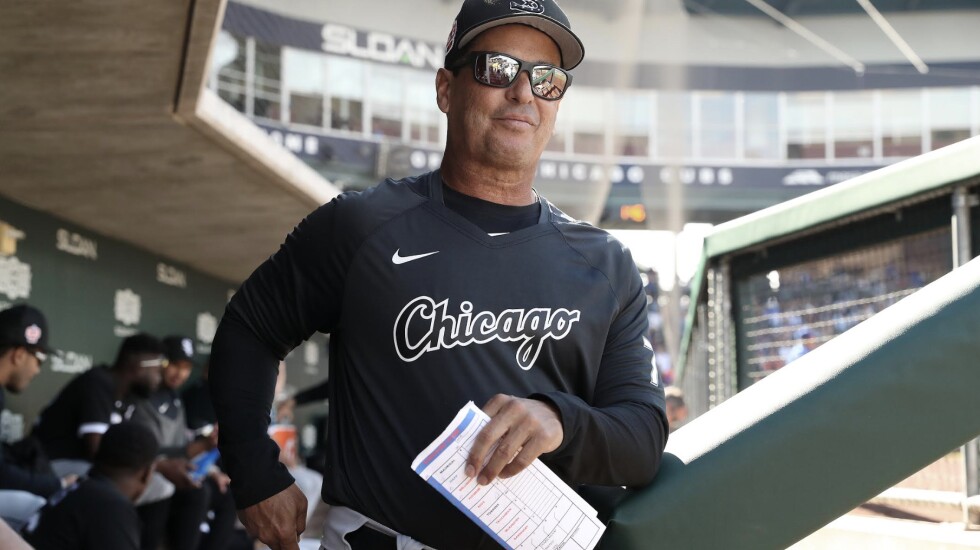

Now 57, Montoyo reflects fondly on three key figures who helped him adjust quickly to become an effective communicator and sustain a 37-year pro career that includes his current role as the White Sox’ bench coach.

The first was the late Don Odermann, a stockbroker and former Peace Corps worker who operated the Latin Athletes Education Fund. The program provided partial scholarships for young Latinos to pursue an education as well as a baseball career. Odermann’s program produced major-leaguers Moises Alou, Jose Bautista, Rafael Bournigal, Bien Figueroa and Montoyo, as well as law enforcement and government officials.

“He’s an angel to me and other guys,” Montoyo said of Odermann, who passed away in 2017 at age 72. “I’m here because of him.”

Montoyo was spotted in a youth tournament in Venezuela. He had intended to play semi-pro ball with the hope of signing with a team before Odermann showed up and offered scholarship money.

Montoyo had spent only three days outside Latin America — in New York for a tournament — before continuing his amateur career at De Anza Junior College in Cupertino, California.

“I stayed in my parents’ bedroom the night before I left,” he said. “It wasn’t easy to fly from Puerto Rico, stopping in Dallas and flying to San Jose without speaking English.”

He was greeted at the airport by De Anza coach and former major-league shortstop Ed Bressoud, who helped him develop into an all-conference infielder and hosted him for the spring quarter.

“When he picked me up at the airport, I had no idea what he was talking about,” Montoyo recalled.

The biggest adjustment came soon after Bressoud dropped Montoyo off at the Obenour house. Father Dave was De Anza’s head athletic trainer. The Obenours left for a Sunday chore, informing Montoyo there was food in the house, but Montoyo elected to look for a McDonald’s, only to get lost trying to return.

“Well, he knew about McDonald’s,” Dave Obenour joked in a phone interview. “Charlie liked my wife Margaret’s Italian food. And we taught Charlie how to use the washer and dryer.

“He has been extremely appreciative of the time he lived here.”

Obenour’s oldest son, Cory, was taking a Spanish class in junior high. Montoyo soon became an unofficial tutor, and Cory did the same for Montoyo with English.

“Was I homesick a little bit? Yes,” said Montoyo, who remains in contact with the Obenours and Odermann’s widow. “But the Obenour family made me so comfortable that it was easy to do the baseball part.”

Montoyo’s popularity swelled to the point where several of his teammates and a few members of the women’s volleyball team provided him with transportation.

“Not having any Latins around helped me learn the language fast,” he said. “That’s what I tell the kids here. If you want to learn the language faster, you’ve got to stay away from your language so you can learn the other one.

“It’s funny because back then, Columbia House used to have the 12 [albums] for one cent. So that’s another avenue [for] how I learned the language, listening to Billy Joel and soul music.”

With the aid of an ESL (English as a second language) course, Montoyo left De Anza a year early to transfer to Louisiana Tech despite being recruited by Santa Clara University (Odermann’s alma mater) and drawing interest from the Rangers.

“[Former Pirates catcher] Junior Ortiz was one of the first ones who told me, ‘You’re going to get to a point that you’re not going to have to think in Spanish anymore to talk English,’ ” Montoyo said. “He was right.”