Sorry, I’m a real f***ing prick,” says Charlie Brooker, just 30 seconds into our conversation. All I did was ask the self-deprecating satirist, seated beside Black Mirror co-producer Annabel Jones, how the day was going. Jones answered, politely, that she’s exhausted. I replied by saying I’m sorry to hear that.

“Are you?” responded Brooker in a patronising tone.

“He’s being very f***ing contrarian,” Jones said, sounding – for lack of a better word – exhausted. “Every f***ing thing.”

“Everything everyone is saying I’m going, ‘Really?’,” Brooker grins.

We’re sitting in a Soho hotel making opening pleasantries because the fifth season of Black Mirror is coming to Netflix. Heavily inspired by Sixties science-fiction anthology series The Twilight Zone, Black Mirror first aired in 2011 on Channel 4. It has been Brooker and Jones’s most successful joint venture yet. Each episode tells a different story about the relationship between humans and technology. More often than not, the results are deeply disturbing.

Yet, despite Black Mirror’s notoriously bleak outlook, the duo behind these grim tales are buoyant company. There are few moments during our conversation when they’re not interrupting one another with undercutting jokes and comments. For instance, I ask what they initially bonded over.

Jones leads: “I don’t think we’ve ever bonded over anything.”

“I’m hoping that will happen one day,” Brooker adds.

What, then, has kept them working together for well over a decade?

“It’s our mutual and healthy disrespect,” Jones answers.

“We’re full of hatred,” Brooker continues. “And it’s probably because we’re unemployable in any other way. We are our own punishment.”

“Oh my God, it’s like Black Mirror Christmas,” she responds, referring to the Jon Hamm-starring episode “White Christmas” in which two antagonistic characters – played by Jon Hamm and Rafe Spall – are trapped in a cabin for five years with only each other to talk to.

“F***ing hell,” Brooker says, his head falling into his cupped hands.

They do, eventually, get to discussing how they met. Around 18 years ago, Brooker – at the time a writer for Channel 4’s spoof news programme The 10 O’Clock Show – was playing the first-person shooter video game Counter-Strike with a group of writers at the headquarters of Endemol (now Endemol Shine), the media company that produces the reality game shows Big Brother, Deal or No Deal and Wipeout.

“Someone had met you before,” he says to Jones, recalling the moment. “And you came in and mercilessly took the piss out of us for quite some time. And I thought, ‘Who the f*** is she? She’s got some gall coming in here and mocking us just because we’re grown-up children in her estimation.’”

“You were in your pants, playing your video games,” Jones says.

“See what I mean?” he says.

Brooker was impressed by Jones’s spirit and the pair ended up working together. Their first collaboration was the 2008 miniseries Dead Set, a Black Mirror forebearer that imagines what would happen to a group of Big Brother contestants if a zombie outbreak occurred outside the house’s walls, which famously saw Davina McCall join the ranks of the flesh-eating walking dead. Since then, the pair have worked together continuously, with Jones becoming an executive producer on Brooker’s ScreenWipe – the current affairs review programmes that solidified Brooker’s reputation as the UK’s top miserablist.

Unfortunately, despite public demand, the show won’t be coming back for its yearly review in 2019. “I’m too busy,” Brooker says. “Which is a pity because it’s the end of the decade. But there’s so much going on and you can’t do half measures. I always like the idea of doing a ‘Final Wipe’. When the world really is about to f***ing end.”

“Is that what you’ll be doing with your final hours?” Jones asks.

“It would be a distraction,” he replies.

She impersonates him: “Oh no the f***ing world is ending. I know, I’ll do a show.”

“You’ll need a f***ing distraction,” he says, faux offended. “If you see the f***ing mushroom clouds going up you’ll be wiping something. Or just wait and it’ll all get burnt off. Sorry, I’m going off track…”

Brooker and Jones’s world-conquering collaboration, Black Mirror, would take form a few years later. The series started off humbly enough in 2011, with the first episode dividing viewers. Titled “The National Anthem”, the episode – the producers call each one a film – saw Rory Kinnear’s prime minister forced by a terrorist kidnapper to have sex with a pig. This, of course, came a few years before allegations that actual PM David Cameron put “a private part of his anatomy” in a dead pig’s mouth during his university years were widely published (Brooker claims to have no prior knowledge of the claim).

After two seasons and a Christmas special, the duo found themselves clashing with Channel 4 about the direction the show should take, with Brooker previously telling Radio Times that the broadcaster thought their ideas for season three “weren’t very Black Mirror”. And so, they moved to the streaming giant.

Season three was released by Netflix in October 2016 and Black Mirror mania took off, with the streaming service beaming the dystopian series directly into homes around the world. A year later and Brooker picked up an Emmy for outstanding writing for the surprisingly optimistic episode “San Junipero” – about two OAPs who meet in a virtual reality world and fall in love. By the time season four came around Black Mirror was an all-out awards behemoth, racking up three Bafta nominations, eight Emmy nominations and a Producers Guild of America Awards win for Brooker and Jones.

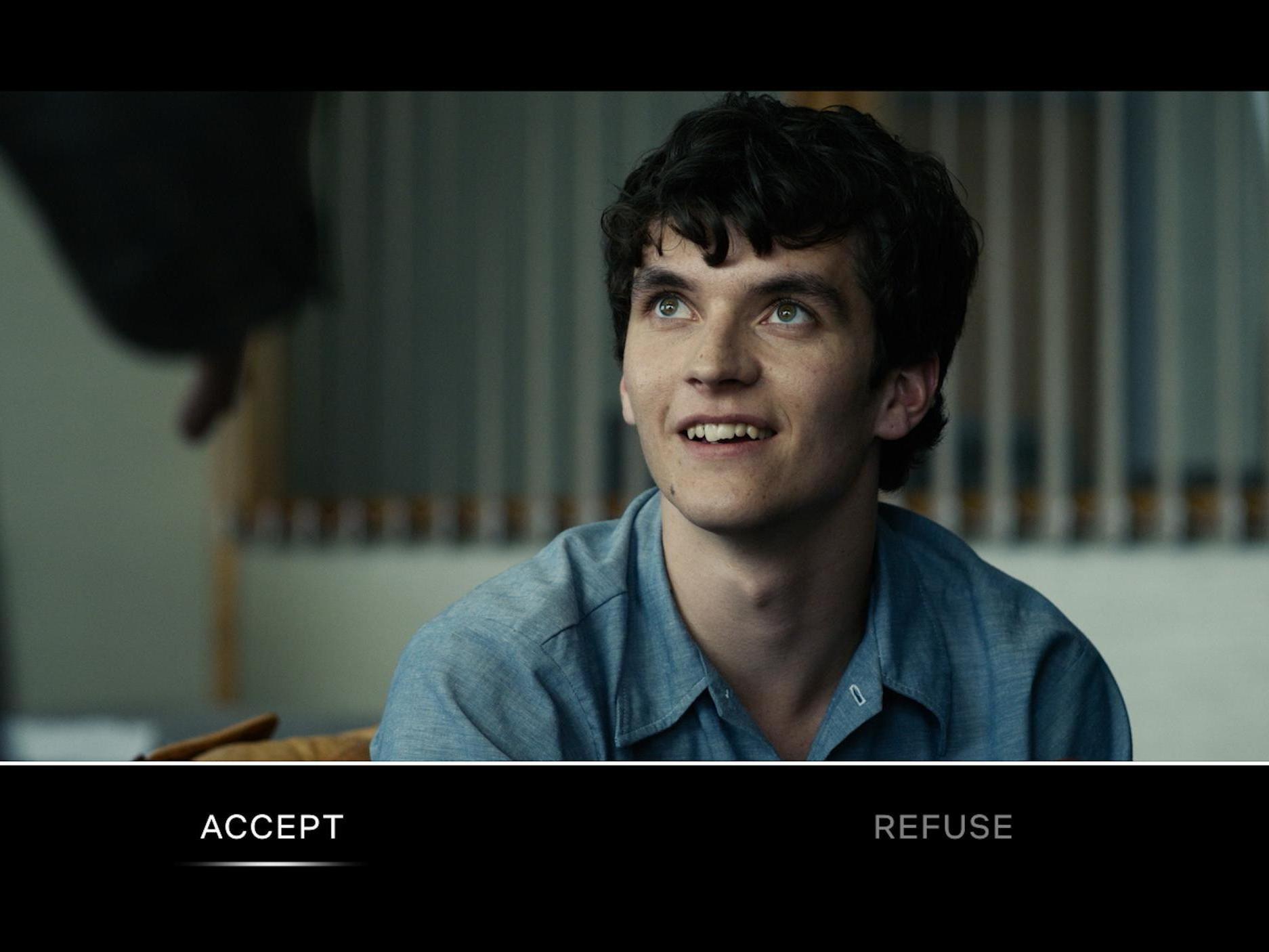

For their next project, the duo knew they had to do something special; something pushing the boundaries of what television can do. The result was Black Mirror: Bandersnatch, an interactive film that allows viewers to choose what happens next to the lead character, Stefan, played by Fionn Whitehead. However, unlike the previous seasons of Black Mirror, the reaction was divided. So much so that one of the actors, Will Poulter, ended up leaving social media.

“We always knew it was experimental,” Brooker says of Bandersnatch. “You’re relinquishing a lot of control and you don’t know which ending the viewer is going to get to first. Are there endings I would change? Probably. For instance, there’s one part which is quite meta, fourth-wall breaking, when you tell Stefan he’s a character on Netflix. Originally, that was held back. But we thought it was so different, so we opened it up early on. What that meant was that some people went down the meta path first and that colours their experience.”

He continues: “One criticism which we thought was a compliment was when people went ‘We just wanted to give him a happy ending!’ Well, thank f*** you cared about Stefan. That was our biggest worry. I play computer games and I don’t give a f*** about the people in them. I don’t give a f*** about Mario because he’s not really a character and he does whatever the f*** I tell him to.”

Jones breaks in: “Expectations were very different. Some people wanted a film, others a video game. The key thing was; did we earn the right to use the interactive form? I think we did. Did we waste the form? We exposed it. We had fun with it. But at the same time, we created a character people cared about. It’s a f***ing complex thing to do, but I was really pleased.”

“No one died, which is the main thing,” Brooker concludes. Jones adds, with perfect comic timing: “Apart from the dad.”

Bandersnatch required a lot of time to complete, which meant Black Mirror’s fifth season was delayed half a year and the episode count halved from six to three. Despite the shortened runtime, though, the new episodes feel like classic Black Mirror, particularly “Smithereens”. In it, Fleabag actor Andrew Scott plays a grieving not-Uber driver who hates how people are addicted to their phones. He decides to take someone hostage and demands to speak to their boss.

“The story came from two things,” Brooker says. “The first was regarding the trust you put in someone when you get in the back of an Uber. I had an experience where I got in the back of the car and I was on my phone. Suddenly, I was wondering where I was. The guy got out and was rummaging through stuff in the boot. I was wondering ‘What is going on?’ It turns out he was just getting a bottle of water out and didn’t want to interrupt me.”

The other nucleus for the story occurred when Brooker began to question how we deal with losing a loved one in an age where their life is stored on social media. This developed into a question of how the relationship between mankind and technology – specifically the mobile phone – has changed in recent years.

“The phone is meant to keep you there,” Jones says. “It’s very interesting how subtly and incrementally the ingredients have changed. Take your email. A little number appears on your homepage showing you how many emails you have not opened. You now need to check those new emails. It’s the gamification of that. Nobody tells you these changes are happening. We’re in an ironic situation now where the phones designed to absorb you are telling you, ‘You’re using me too much.’ It’s not common sense telling you – it’s the phone.”

Brooker comes in with a comparison: “It’s like a cigarette saying, ‘I think you should cut down a bit’. Or a barman going, ‘I think you’ve had enough.’”

“It’s f***ing nuts,” Jones adds.

The second episode, titled “Striking Vipers”, revolves around two middle-aged men; one who is married (Anthony Mackie) and one who is not (Yahya Abdul-Mateen II). They begin playing a virtual reality fighting game named “Striking Vipers”. Mackie’s character uses a male avatar, while Abdul-Mateen’s uses a female. They engage in an unusual relationship.

“In a world where pornography is so immersive, when does it stop becoming a healthy distraction and become an affair?” asks Jones, positing the moral quandary at the episode’s centre.

Brooker continues: “The funny thing is, the germ for the idea came from the fighting game Tekken. If you’ve ever heard two guys playing Tekken or Street Fighter, it sounds like a sadomasochistic sex scene. They go ‘oof, ahhh, argh, yes, YESSS’.”

Brooker adds that his Tekken character of choice would be the boxing kangaroo Roger. Mine would be Taekwondo fighter Hwoarang.

Jones joins the discussion: “I’m not familiar with these works of genius.”

Brooker: “That was very disparaging.”

“I’m not. I’m just not familiar with them.”

“They’re lightning-speed chess games is what they are.”

“Lightning-speed chess?”

“Because it’s about countering everything. If they do this [Brooker karate chops the air], I have to do this [he blocks an imaginary punch]. It’s just like our fights. But you would beat me because you’re f***ing…” he leaves that hanging.

The final episode of the season centres on an Alexa-type piece of technology that has the personality of a pop star. The twist comes when that pop star (played by Miley Cyrus) starts breaking down due to the pressure of the pop industry. Brooker jokes that, if any Black Mirror episode was to come true in the near future, it would be this one, “Rachel, Jack and Ashley Too”. Perhaps, I wonder, the story is therefore a warning about the future?

“Our stories are not warnings,” Brooker says. “Technological progress is completely inevitable. We think more about the human characters. They’re not societal warnings. And I think we’re quite optimistic.”

A pause. Brooker knows full well that any avid Black Mirror watcher would likely object to the statement. He picks a modern example to explain his reasoning: how information is shared on the internet and the rise of fake news.

“I assume it’s like when the printing press started,” he says. “Back in the day, they probably disseminated ideas that were idiosyncratic and inflammatory. There would have been all sorts of disruption. You would hope, long term, we’re going through a transitional period and we just happen to be in the middle of it.”

Jones chips in: “We shouldn’t forget that people are being mobilised. You have the #MeToo movement, and the campaign for climate change. All these people suddenly have a voice. They’re a commercial body who will bring about change from the capitalists who are doing damage to the environment.”

Brooker continues: “We’re in that period of finding out what’s in people’s heads. You get extremes being presented, but I think the world feels more polarised than it actually is.”

Who knew that the creators of the often-grim Black Mirror – that “f***ing prick” Charlie Brooker and the exhausted Annabel Jones – were such optimists?

Black Mirror season five reaches Netflix on 5 June