King Charles III, the self-confessed “interferer and meddler”, appears to have admitted he will take a step back from campaigning on issues now he is head of state.

GM crops, nanotechnology, monstrous carbuncles, the environment, farming and complementary medicine have all provoked comment from the royal during the past decades.

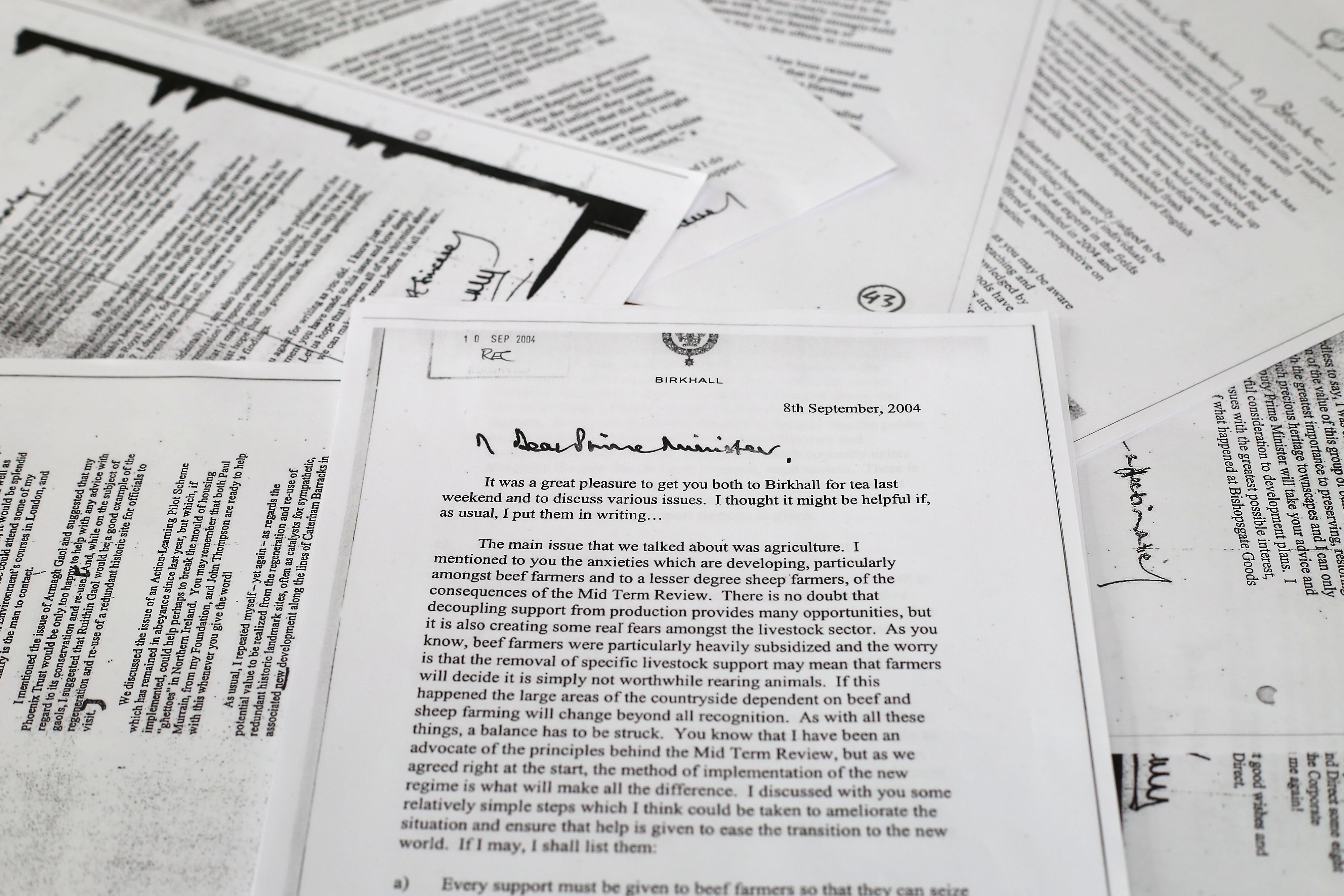

But his famous notes to ministers – known as “black spider” memos because of his distinctive handwriting and abundant use of underlining and exclamation marks – are now likely to remain unwritten.

In his address to the nation during his first full day as king, Charles, 73, signalled his new role would bring fundamental changes to his life and for his family, and reduced involvement in campaigning on issues and working with his charities.

He said: “My life will of course change as I take up my new responsibilities. It will no longer be possible for me to give so much of my time and energies to the charities and issues for which I care so deeply. But I know this important work will go on in the trusted hands of others.”

When Charles turned 70, he insisted his meddling would not continue when he acceded to the throne.

“No, it won’t. I’m not that stupid,” he told a BBC documentary in 2018. “I do realise that it is a separate exercise being sovereign. So, of course I understand entirely how that should operate.”

Concerns were often raised as to how his opinions would feature when he became monarch, and he will be under intense scrutiny as the new King.

Being an inveterate interferer and meddler I couldn't possibly stand back and do nothing— Charles in 2008

Sources close to Charles told The Guardian in 2014 that he would break with tradition and make “heartfelt interventions” in national life.

They said he would not follow his mother’s discretion on public affairs but instead speak his mind on issues such as the environment.

Catherine Mayer’s 2015 unauthorised biography of Charles said the prince was planning to introduce a “potential new model of kingship” but that the Queen was concerned about the potential style of the monarchy under her son.

But Charles’s senior aide at the time, principal private secretary William Nye, came to his defence, saying Charles understood “the necessary and proper limitations” on the role of a constitutional monarch.

As head of state, Charles is a non-political figurehead and must remain strictly neutral.

Royal advisers may have attempted to curb his controversial views in the past but the prince often hit the headlines, particularly over his lobbying of ministers.

Politicians were said to have regularly moaned about the number of letters they received from the crusading prince – the “black spider” memos.

In 2002, he found himself at the centre of a constitutional row following revelations he had been “bombarding” ministers with letters attacking government policy.

One minister said that the prince had become so involved in politics that he wrote a letter a week to the Government.

It emerged he had written a series of letters to the then lord chancellor, Lord Irvine of Lairg, expressing concern over the growth of the “compensation culture” and the Human Rights Act.

The prince warned that human rights legislation is “only about the rights of individuals… and this betrays a fundamental distortion in social and legal thinking”.

Charles also took issue with the “degree to which our lives are becoming ruled by a truly absurd degree of politically correct interference”.

He has not always wanted his views to be made public.

Letters he wrote to a number of government departments between 2004 and 2005 became the subject of a protracted legal battle over whether their contents should be disclosed.

Twenty-seven letters, 10 from Charles to ministers, 14 by ministers and three letters between private secretaries, were released in 2015 following a 10-year campaign by Guardian journalist Rob Evans to see the documents after a freedom of information request.

The publication of the correspondence showed the prince lobbied then-prime minister Tony Blair and other ministers on a range of issues from badgers and TB to herbal medicine, education and illegal fishing.

He also tackled Mr Blair over a lack of resources for the armed forces fighting in Iraq.

There were no handwritten “black spider” letters among the batch released.

In 2006, Charles’s former aide Mark Bolland revealed at the High Court that the prince saw himself as a “dissident” working against current political opinion.

Charles’s journals, around which the case centred, published in the Mail on Sunday revealed that he made unflattering comments on the handover of Hong Kong to China when he described Chinese diplomats as “appalling old waxworks”.

In 2008, the prince declared frankly, referring to his involvement in a restoration project in Bradford: “Being an inveterate interferer and meddler I couldn’t possibly stand back and do nothing.”

Charles has also been outspoken on architecture.

Speaking in 1984 about the proposed National Gallery extension, he stated: “What is proposed is like a monstrous carbuncle on the face of a much-loved and elegant friend.”

In May 2009, he became embroiled in a new row concerning a development at Chelsea Barracks.

The prince contacted representatives of the Qatari royal family, who own the London site, suggesting that Richard Rogers’ designs for a £1 billion housing scheme on the site of the former barracks were “unsympathetic” and “unsuitable”.

The new King will meet the Prime Minister every week at a private audience where he may express whatever opinions he likes.

In fact the British monarchy website declares it is the sovereign’s “right and a duty to express (his) views on Government matters”.

But it adds that “having expressed (his) views, The (King) abides by the advice of (his) ministers”.