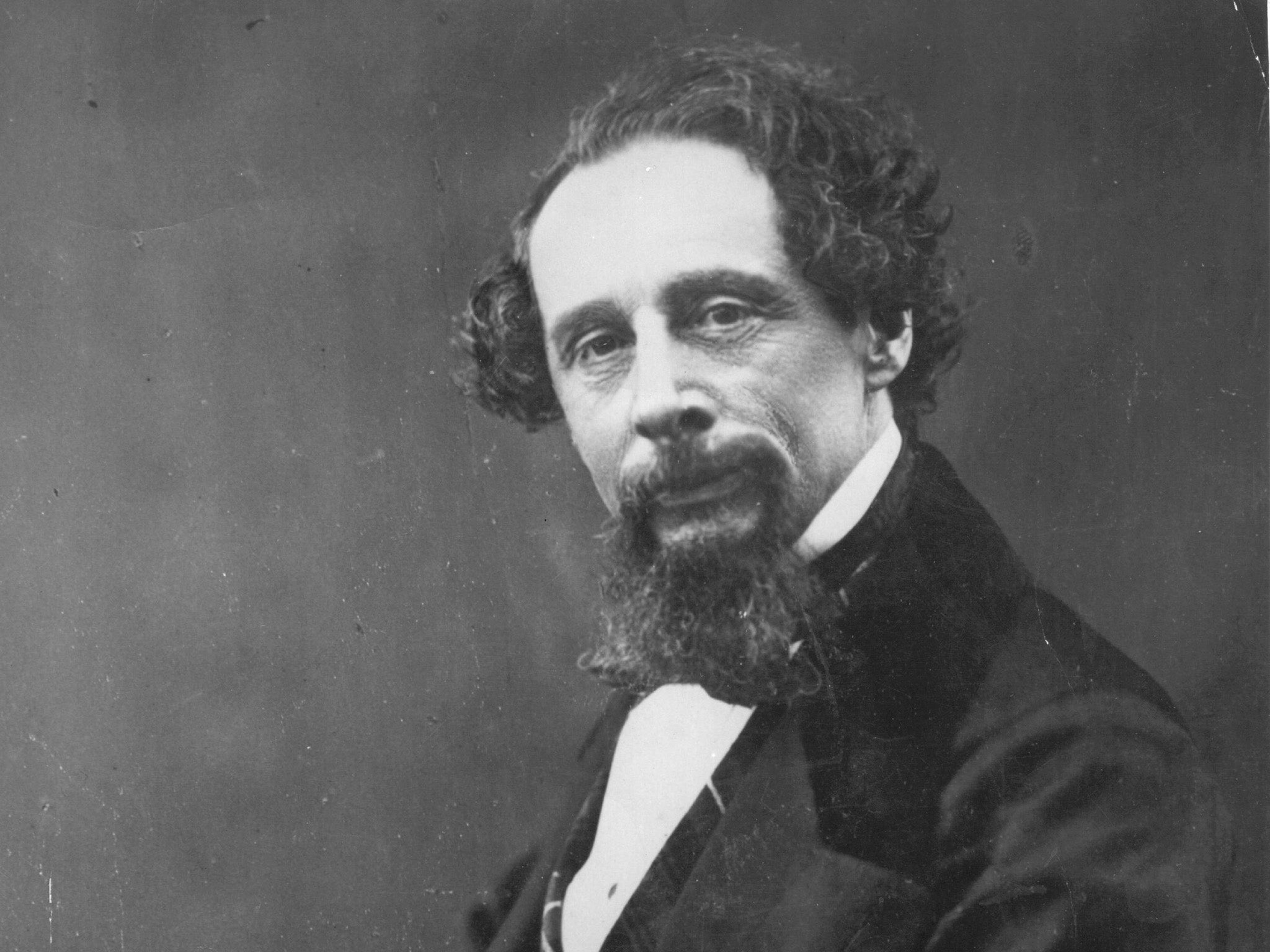

Few writers are as closely associated with the festive season as Charles Dickens.

His novella A Christmas Carol, which first went on sale on 19 December 1843, remains Britain’s favourite secular Christmas story, dusted down and revisited every year without fail.

Stephen Tompkinson playing miserly moneylender Ebeneezer Scrooge at The Old Vic this year is only the latest interpretation of a character who has provided the basis for every contrite naysayer since, from George Bailey in It’s a Wonderful Life (1946) to Dr Seuss’s Grinch. Alastair Sim’s wonderful portrayal of 1951 remains the Scrooge to beat.

Dickens was motivated to write his ghost story by a deeply felt outrage at the hardships of the urban poor he saw every day on the streets of Victorian London and the unfeeling avarice of the arch-capitalists of his age.

The author had known poverty himself as a child after his father John was incarcerated in the Marshalsea Prison in Southwark for debt, forcing the young Charles into hard labour at a boot-blacking workhouse.

In the winter of 1843, Dickens had visited Clerkenwell’s Field Lane Ragged School, a recently founded charitable institute for urchins. The deprivations of the pupils he encountered there only stirred his indignation.

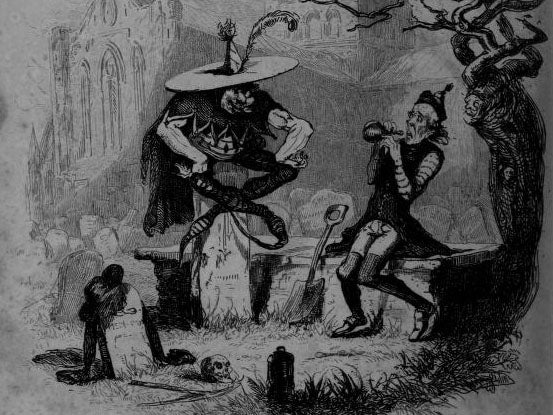

Resolved to address his concerns in fiction, Dickens returned to an idea he had first touched upon in The Pickwick Papers (1836): the sinner reformed by supernatural intervention. In that novel, Mr Wardle tells the story of Gabriel Grub, a church sexton visited by goblins, who show him his past and future and inspire a more charitable attitude.

The Berkshire MP John Elwes and Jemmy Wood, owner of the Gloucester Old Bank – two men known as notorious spendthrifts – have both been citied as possible inspirations for Scrooge, whose name was taken by Dickens from a gravestone spotted in Edinburgh and whose philosophy serves as a satire on flint-hearted Malthusian economics.

The tale of Scrooge’s conversion from penny-pinching humbug to zealous altruist provided a cheering moral, but also set in stone our popular conception of the Victorian Christmas, a time of candlelight and plum pudding, undoubtedly two central reasons for its enduring popularity.

But Charles Dickens is not just for Christmas. While many will know A Christmas Carol intimately, the sheer length of many of his other works too often proves a deterrent.

Many readers will plump for The Old Curiosity Shop (1841) or Hard Times (1854) for their comparative brevity but, in truth, neither represents Dickens at his best. As Oscar Wilde so savagely observed: “One must have a heart of stone to read the death of Little Nell without laughing.”

Here’s our selection of Dickens's 10 finest novels, any one of which would provide ideal reading in the long dark nights to come.

10. A Tale of Two Cities (1859)

Dickens’s foray into the French Revolution, inspired by a reading of Thomas Carlyle’s history of the Terror, is atypical of his output and certainly imperfect but a rollicking ride nonetheless.

The tale of Dr Alexandre Manette, freed from the Bastille after 18 years and newly arrived in England, where he is reunited with his daughter, Lucie. She marries the exiled French aristocrat Charles Darnay, who is drawn back to his homeland as the Reign of Terror erupts, the revolutionaries driven on by shopkeeper Ernest Defarge and his fearsome, vengeful wife Therese.

Only Sydney Carton, an alcoholic English lawyer also in love with Lucie, can help Darnay, a man he closely resembles.

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times,” Dickens begins, offering one of the most famous opening lines in literary history.

Incredibly, he manages to surpass it at the close, with Carton’s desperately moving words as he awaits the guillotine: “It is a far, far better thing that I do, than I have ever done; it is a far, far better rest I go to than I have ever known.”

9. Martin Chuzzlewit (1844)

The author’s earliest novels followed the picaresque format of his 18th-century forebears, notably Henry Fielding and Tobias Smollett, with Chuzzlewit recounting its title character’s being disinherited by his wealthy grandfather and forced to work as an apprentice for the comically self-serving architect Seth Pecksniff, a villain keen to wangle the Chuzzlewits out of their fortune.

Chuzzlewit is best known for its second act, in which Martin sets out for America only to find the New World populated by fraudsters and the town of “Eden” to be a malaria-ridden swamp in dire need of draining.

A ripe piece of satire drawn from the author’s own experiences of the United States, which he had visited on a reading tour in 1842, Chuzzlewit leaves one chomping at the bit to imagine what the writer might have made of Donald Trump.

Pecksniff is a joy but, among the supporting cast, the gin-totting midwife Sarah Gamp is not to be missed, a particularly magnificent feat of comic characterisation.

8. Barnaby Rudge (1841)

Like A Tale of Two Cities, Barnaby Rudge is a historical novel set half a century earlier, this time dealing with the Gordon Riots of 1780, a populist anti-Catholic uprising inspired by Lord George Gordon’s inflammatory rhetoric against the Popist “infiltration” of Britain. Their cause has uncomfortable echoes of the far-right Islamophobia of today.

Dickens uses the appalling conduct of the rioters as a means of attacking mob violence and, particularly, the hijacking of political causes for crude personal gain. The hangman Ned Dennis, who loves his work, is a deeply chilling figure.

7. Nicholas Nickleby (1839)

Nickleby contains some of Dickens’ very best character work. The vile Wackford Squeers, proprietor of Dotheboys Hall in Yorkshire, is a more pantomime assault on wayward educators than Gradgrind in Hard Times but all the funnier for that. The everyday evil of Ralph Nickleby though (another miser) is no laughing matter.

His fall at the hands of Newman Noggs, a man he has effectively enslaved by obligation, can only be read with a rousing cheer in a book that contains nothing close to a dull moment.

Nicholas’s spell as a repertory actor with Vincent Crummles’ theatre troupe and the tragic fate of Smike are equally stellar.

6. The Pickwick Papers (1837)

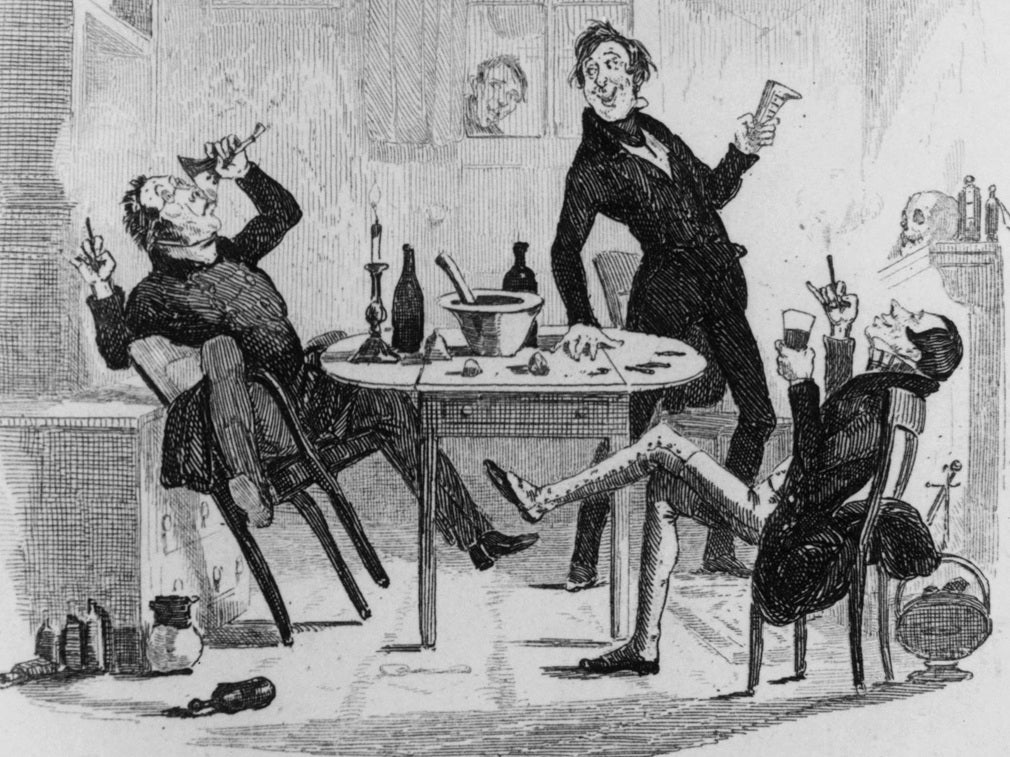

Commenced as a serial when the writer was just 24 and employed as a parliamentary correspondent, Dickens’s first novel strongly reveals his early debt to Fielding and Smollett and is also perhaps his most consistently funny book.

The tale of clubman Samuel Pickwick, who sets out like Don Quixote in pursuit of adventure in the naive company of messrs Winkle, Snodgrass and Tupman, planning to report back on their exploits to an enraptured audience of fellow Pickwickians.

Pickwick’s arrest and imprisonment in the Fleet for “breach of promise” after a misunderstanding with his landlady is hilarious, as is the clipped bluster of Alfred Jingle, the snoring of Joe and the wit and wisdom of Sam Weller, one of the great English everymen.

The Papers also marked the commencement of Dickens’ fruitful partnership with Hablot Knight Browne (“Phiz”), who took over as illustrator after the suicide of Robert Seymour. Only George Cruikshank would match Phiz in lifting the author’s unique creations off the page.

5. Little Dorrit (1857)

Lawyer Arthur Clennam, returned to London from China, befriends angelic seamstress Amy Dorrit and is shocked to find her supporting her father William Dorrit, imprisoned in the Marshalsea for debt (as Dickens’ own parent had been) for more than 20 years. Known as “the Father of the Marshalsea”, Dorrit is respected by his fellow inmates and too vain to acknowledge his daughter’s efforts on behalf of the family.

Arthur sets out to help, pulling on the thread and unravelling Dorrit’s financial affairs to the betterment of all, only for Clennam himself to be hit by calamity and end up taking his place.

Fresh from lambasting the judicial system in Bleak House, Dickens here went after the machinery of government through his portrayal of the “Circumlocution Office”, staffed entirely by a dynasty of Barnacles positively thriving on the business of chaos.

As in A Christmas Carol, poverty and the social structures in place to keep the downtrodden low are again his true target.

4. Oliver Twist (1839)

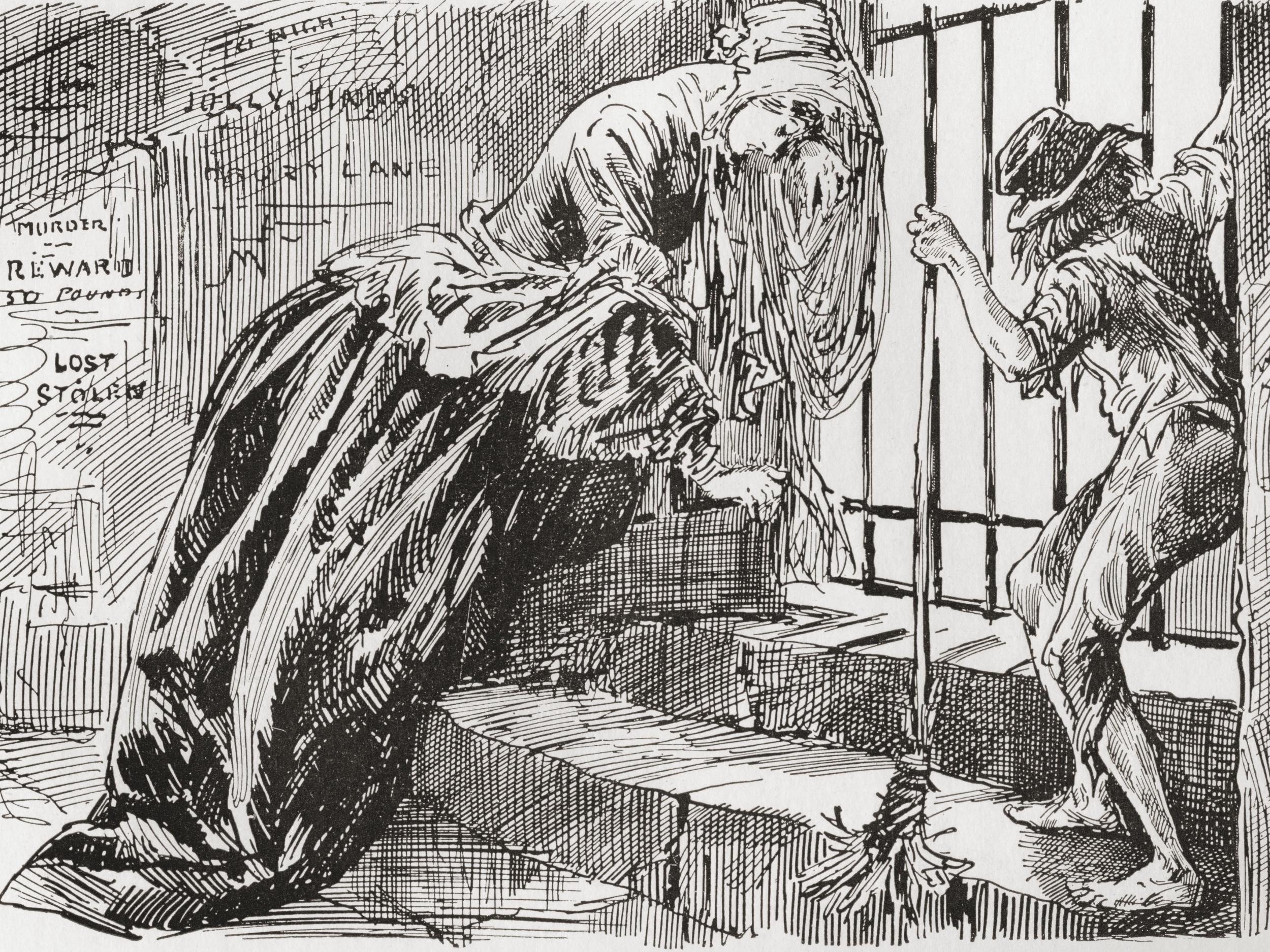

Perhaps the best known of the author’s stories outside of A Christmas Carol, Oliver Twist casts its orphan hero among the thieves of London: Bill Sikes, Fagin and the Artful Dodger.

Dickens used his own unhappy adolescence in the workhouse to sketch in Oliver’s childhood under Mr Bumble and his experience as a journalist to report the plight of street children, forced into pickpocketing and worse by desperate necessity.

Sikes’s murder of Nancy is one of the most terrifying passages in literature and elevates the whole undertaking.

3. Bleak House (1853)

Dickens had begun his attack on the in-built absurdities of the bureaucratic behemoth that is the British legal system with Dodson and Fogg in Pickwick and revisited his contention that “the law is an ass” here to extraordinary effect.

The seemingly never-ending case of Jarndyce and Jarndyce at its centre rumbles on indefinitely, gradually chewing up the disputed inheritance in question until no one can remember its origins and there are no spoils left for the victor in any event: “Innumerable children have been born into the cause; innumerable young people have married into it; innumerable old people have died out of it.”

The kindly Chancery lawyer John Jarndyce meanwhile finds himself legal guardian to Esther Summerson – unknowingly the daughter of Lady Dedlock, whose past drives the mystery - and to Richard Carstone and Ada Clare, the wards of court who fall in love and hope the case will be resolved in their favour.

Harold Skimpole – a sponging associate of Jarndyce who disingenuously insists on his state of childlike innocence to wheedle his way out of adult responsibility – and the ludicrous dancing master Turveydrop appear among another unforgettable supporting cast.

2. David Copperfield (1850)

This masterly bildungsroman charts the life and adventures of the eponymous hero, dispatched to live in an upturned boat on Yarmouth beach after his unworldly mother marries the cruel Edward Murdstone.

After boarding school and an unhappy stint in London, David is befriended in Dover by his monomaniacal aunt Betsy Trotwood before encountering the tippling lawyer Mr Wickfield and his “dreadful ‘umble” assistant Uriah Heep, the latter slyly seeking to usurp the former.

Betrayed by his schoolmate Steerforth, David rises to prominence as a novelist, has his heart broken by tragedy and ultimately finds lasting happiness.

Once more drawing on aspects of his own past, Dickens is on supreme form here. In the person of Wilkins Micawber, he offers another quietly devastating portrait of his own hapless father, perennially in debt and unfailingly optimistic of a brighter tomorrow. WC Fields’s portrayal in the 1935 MGM film is unmatched.

Armando Iannucci is nevertheless currently working on a new adaptation of Copperfieldstarring Dev Patel.

1. Great Expectations (1861)

Dickens achieved perfection with this gothic masterpiece about the ascent of a blacksmith’s apprentice from the Kent Marshes to the status of affluent London gentleman after he is bequeathed a fortune by a mysterious benefactor.

Pip erroneously assumes his patron to be Miss Haversham, an eccentric brewery heiress who has vowed revenge against all mankind after being jilted on her wedding day, but the truth is far more shocking.

Abel Magwitch, Pumblechook, Estella, Herbert Pocket, Jaggers the lawyer, Wemmick and the Aged P, Bentley Drummle and the heartbreaking Joe Gargery – all life is here.

Haversham, sat alone in her mansion wearing white, a three-tiered cake mouldering at her side, utterly consumed by hatred, would be worth the price of admission alone.

You can’t do better than David Lean’s version of 1946 with John Mills, Martita Hunt, Jean Simmons and Alec Guinness.