Four months before he died, Charles “Chuck” Caldwell Jr. gave his wife a stuffed “Paw Patrol” dog for her birthday.

It was a replacement. The original, named “Gumbo,” had been given to Darnell Caldwell by her grandson to “protect her” as she slept on airplanes on her shifts as a flight attendant.

When Mr. Caldwell saw how heartbroken she was that she had left Gumbo on a plane, he went to Build-A-Bear and bought her an identical dog — the only difference being that Mr. Caldwell’s heartbeat sounded from the new toy at the press of a button.

“To put that heartbeat inside was the most divine thing God could’ve ever had him do for me because it’s priceless,” Darnell Caldwell said.

Mr. Caldwell died Aug. 27 from a medical episode in New Orleans. He was 44.

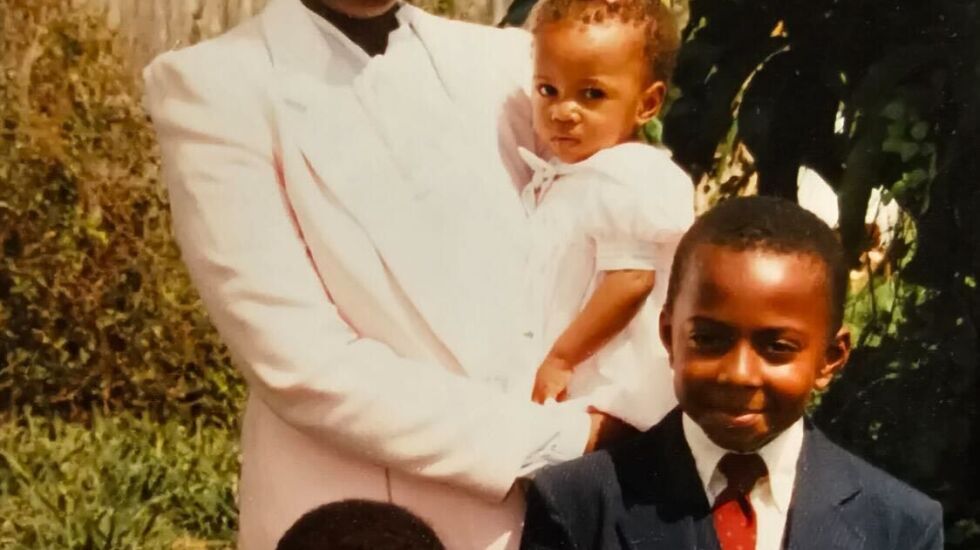

Mr. Caldwell was born Dec. 23, 1978, in Chicago, and shortly thereafter, moved with his family to Florida, where he was raised. He spent summers in Chicago with his grandparents in Avalon Park.

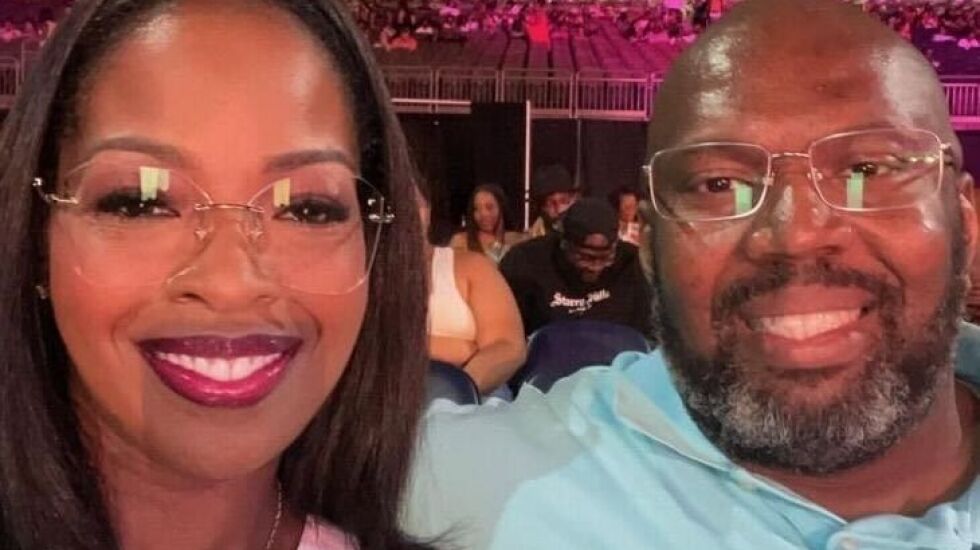

Mr. Caldwell and his wife met at Harrah’s Casino in New Orleans where they once worked. They dated for two months before tying the knot on Oct. 6, 2004.

Darnell Caldwell described her husband as a “very analytical guy who did nothing spontaneous.” He’d joke with her about how marrying her was the only spontaneous thing he had ever done.

Mr. Caldwell’s parents and siblings shared Darnell’s sentiments about him being analytical, saying he was “always 10 steps ahead.”

His father described him as a cerebral football player. His brother said he was a typical big brother.

“He was always the first to make a sacrifice,” Christopher Caldwell, Mr. Caldwell’s brother, remembered. “He was always the first to see that there was a need and then fill it.”

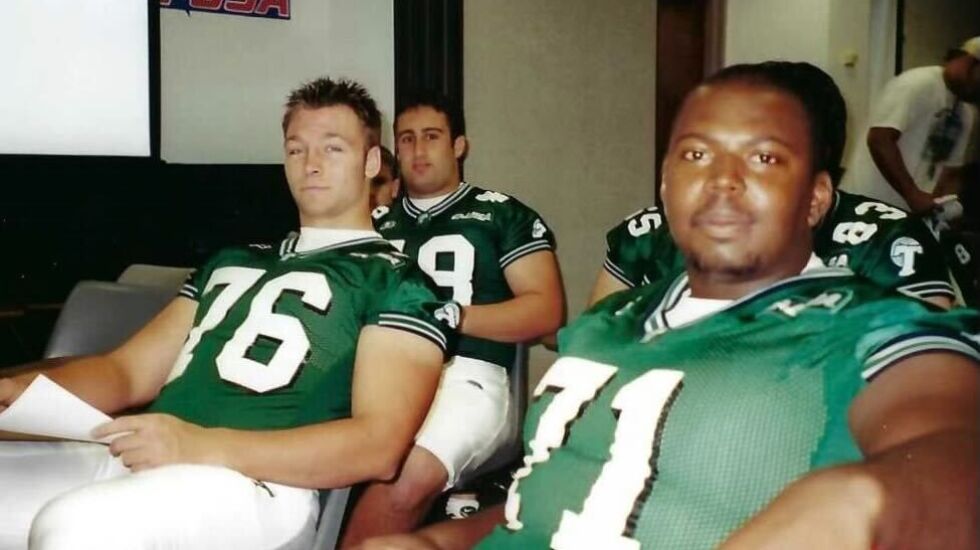

He played defensive lineman and offensive guard for Santaluces Community High School in Florida and accumulated a case full of trophies, according to a funeral obituary written by his uncle, Sun-Times columnist Lee Bey. After developing into a highly recruited senior by 1997, he chose to attend Tulane University in New Orleans.

A back injury derailed Mr. Caldwell’s dream of an NFL career. The Cincinnati Bengals remained interested in him, according to Charles Caldwell Sr., his father, but Charles Sr. didn’t trust the surgery required to rehabilitate his son.

After missing out on his dream to play in the NFL, Mr. Caldwell pivoted and graduated with a degree in computer science in 2002.

He worked his way up to become director of infrastructure for Penn National Gaming, where he led a team of eight network and systems engineers and provided key support for 41 casinos across the U.S.

Mr. Caldwell’s determination to succeed beyond any limitations in front of him was a trait he carried since he was young.

When they were kids, Mr. Caldwell and his brother were in their grandmother’s basement, determined to build a go-kart with whatever spare pieces they could find.

The pair hammered bolts into wood, used lawnmower tires as wheels and knotted a rope to steer. Before long, the brothers were pushing each other around the block in their homemade go-kart.

Decades later, Mr. Caldwell’s leadership and determination continued to touch those around him.

He bought his brother computer equipment and texted him articles about computer design years after Christopher gave up on pursuing a career in the field.

When his wife wanted to quit nursing school after failing a test, Mr. Caldwell refused to let her.

He drove her from New Orleans to Baton Rouge and told her she “wasn’t stopping until someone told her no.”

She graduated from nursing school in 2015, and Mr. Caldwell’s phrase became a mantra she repeated when she became a flight attendant for Delta Air Lines last November while continuing to work as a nurse.

“It just was not the thing I wanted to hear at that time, but it was just what I needed to hear,” Darnell said.

Whether in football or in life, Mr. Caldwell had the “ability to read people” — a trait he got from his mother, his family said. He often based some of his interests around the interests of those he loved.

“Chucky was always interested in what I was interested in,” said his sister, Cherise.

They bonded when Mr. Caldwell — knowing that his sister loved plants — started growing and expanding his plant collection.

The last time Mr. Caldwell saw his family, they prayed together in the family’s garage in Hoffman Estates at 4 a.m. as he prepared to make the 12-hour trip back home to New Orleans.

“He knew that we loved him,” Claudette Caldwell, his mother, said. “Those were our last words to him, collectively and individually.”

Services for Mr. Caldwell will be held Thursday in New Orleans.

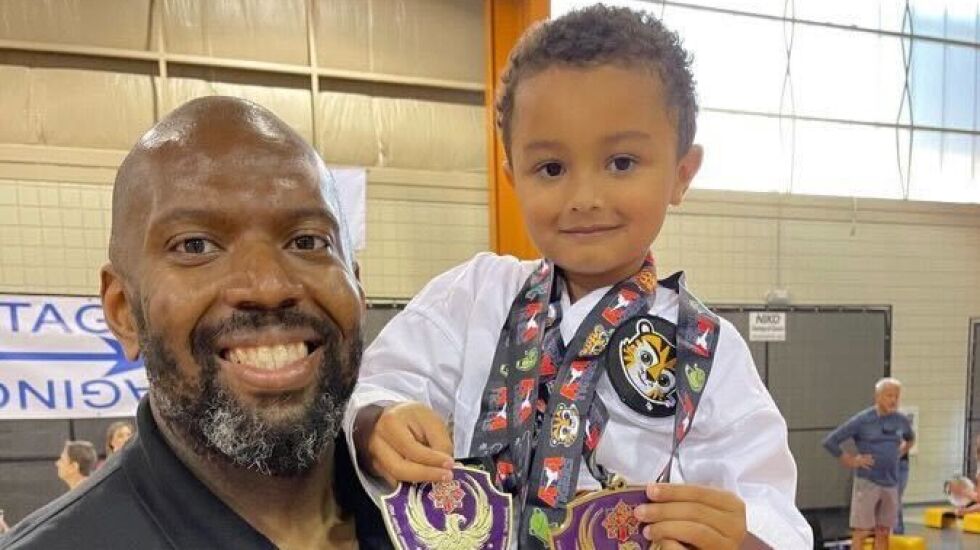

In addition to his parents, siblings and uncle, he is survived by his daughter, Jonnel and her sister, Essence Henry; grandson, Karson; mother-in-law, Lois; father-in-law, Lou; and many aunts, cousins and friends.