Cervical cancer deaths have fallen sharply among young women in the United States since 2013, new research reveals.

According to data from the National Center for Health Statistics, a government agency, around 13 women aged younger than 25 died from cervical cancer between 2019 and 2021, compared to 35 between 2013 and 2015 — a 62% decrease in cancer-related deaths.

Researchers described their findings in a study published Wednesday (Nov. 27) in the journal JAMA. They say the study is the first of its kind to suggest that vaccination against human papillomavirus (HPV) is now preventing cervical cancer deaths in young women, specifically. HPV vaccination was introduced in the U.S. in 2006. It works by preventing high-risk HPV infections, the most common cause of cervical cancer.

"This is a critical milestone in the public health success story of this cancer prevention intervention," Ashish Deshmukh, study co-author and an associate professor at the Medical University of South Carolina, told Live Science in an email.

Related: New self-swab HPV test is an alternative to Pap smears. Here's how it works.

"The findings signify the importance of continued improvement in the HPV vaccination rates in the U.S.," Deshmukh said.

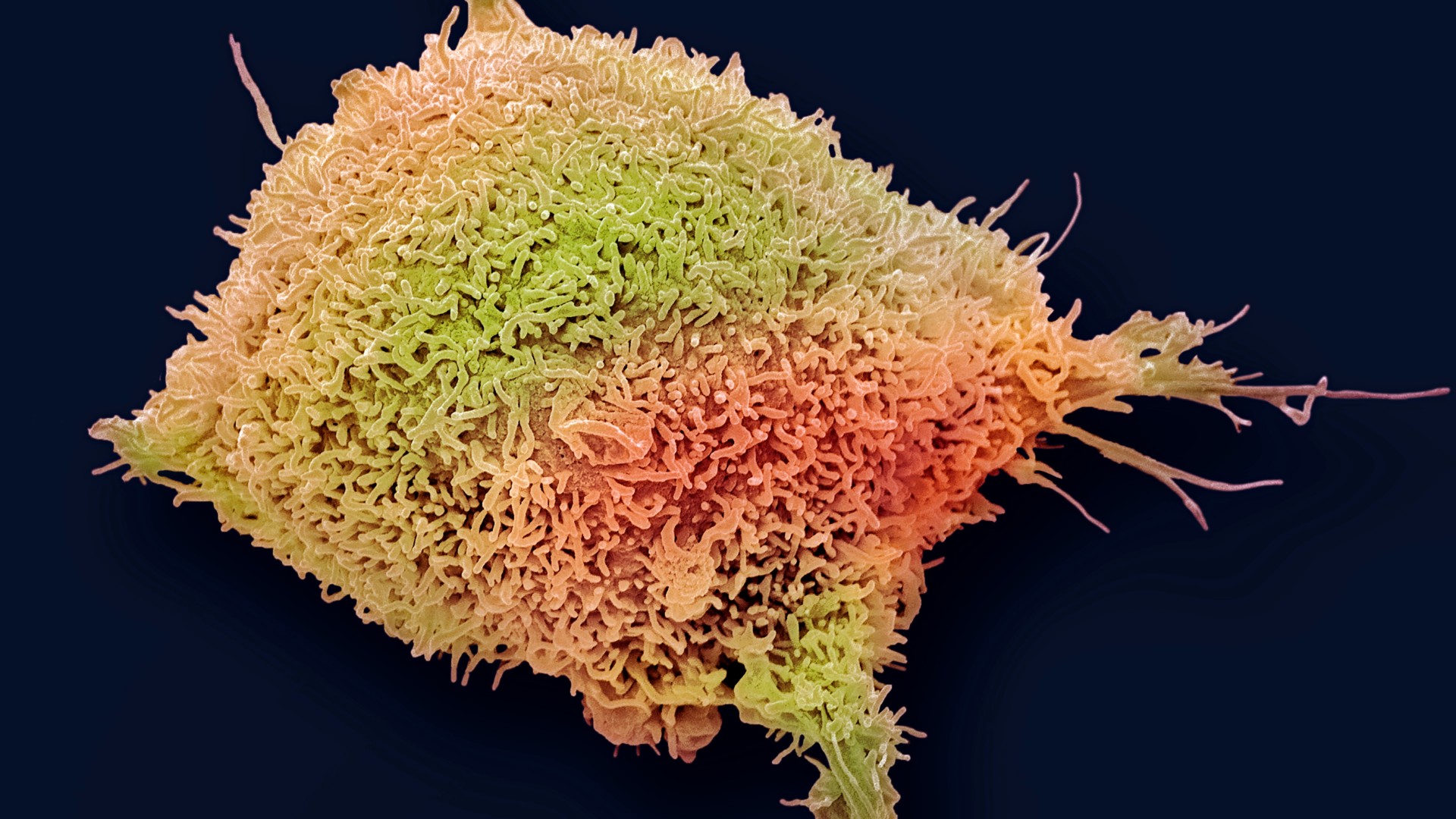

Cervical cancer develops in the cells of the cervix — the lowest part of the uterus that connects the organ to the vaginal canal. In most cases, cervical cancer is triggered by specific strains of HPV infecting cervical cells and thus altering their DNA so they grow uncontrollably.

The disease is the fourth-most-common type of cancer among women worldwide. However, it is highly preventable thanks to vaccination and regular cervical screening. It is also curable through treatments such as surgery and chemotherapy, if it is caught early enough. Unfortunately, because of health inequities, around 94% of deaths from cervical cancer occur in people living in low- and middle-income countries.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that both male and female children get vaccinated against HPV at age 11 or 12. Vaccination can be started as early as age 9 for certain people, such as those who are immunocompromised. And if someone wasn't vaccinated in childhood, they could get the shots as late as 26 years old, or even later, if their doctor recommends it. People who start the vaccine series before their 15th birthday typically need two doses; those vaccinated later need three.

Since the vaccine's introduction, HPV vaccination rates in the U.S. have increased steadily, with 2023 data suggesting that approximately 76.8% of adolescents ages 13 to 17 have received at least one dose of the vaccine. However, vaccination rates appear to have stalled.

"Unfortunately, the current rate [of HPV vaccination in the U.S.] is still suboptimal and way below the Healthy People goal of 80%," Deshmukh said. This goal was set by the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, part of the Department of Health and Human Services. The goal's original deadline was 2020, when the department aimed to increase HPV vaccination rates among females ages 13 to 15 to 80%. This feat, which was not achieved by 2020, strove to have at least 4 in 5 girls in that age group protected by at least two doses of the HPV vaccine.

The new study didn't directly compare cervical cancer deaths with rates of HPV vaccination, so from the data at hand, the researchers cannot say the latter drove down the former. However, numerous other studies have provided evidence that vaccination has dramatically reduced HPV infections along with cervical cancer cases, as well as deaths associated with the disease.

Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, director-general of the World Health Organization, said on Nov. 18 that the elimination of cervical cancer is "within our reach."

"Unlike most other cancers, almost all these cases and deaths can be averted," he wrote. Addressing worldwide inequities in access to HPV vaccines, as well as diagnostic tests and treatments for HPV and cervical cancer, could make cervical cancer the first cancer to ever be eliminated, Tedros said.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!