A century-old church in the Pilsen neighborhood that’s been at the heart of a contentious fight to save it since it closed in 2019 will now have the city of Chicago for a guardian angel.

On Monday, the city’s Landmarks Commission announced that St. Adalbert, as well as a few adjacent structures in the 1600 block of West 17th Street, will get a preliminary landmark recommendation — a move that is just the first step in the landmarking process but protects the building from being sold or dismantled.

“St. Adalbert has been a prominent feature of the Pilsen neighborhood for over a century,” the commission said, adding that its distinct appearance and history represent an established and familiar visual feature of the neighborhood and of Chicago.

The church and its 185-foot towers have stood over the neighborhood since its construction in the early 1900s, but its fate has been uncertain since the Archdiocese of Chicago closed it in an effort to consolidate parish resources.

Its owners have tried to sell it, calling it a “huge drain” on parish funds; preservationists have fought to save it, viewing it as an icon of the neighborhood and for Chicago’s Polish community.

Monday’s meeting was moved from its typical small space to the City Hall council chambers to accommodate the dozens who showed up in support of the recommendation, and the commission’s announcement was met by loud applause from the packed gallery.

A spokesperson for the city’s Department of Planning and Development noted the special meeting was convened after preservationists reported the archdiocese was removing stained glass from the building, which is among the last of its valuable features yet to be removed.

“Given the work that was initiated this week without notice, the preliminary recommendation is moving forward to help ensure the complex’s significant features are preserved,” said Planning Department spokesperson Peter Strazzabosco in a statement.

Strazzabosco noted that the preliminary recommendation would “require permits to be issued by [the Department of Buildings] for certain work that is currently allowed without a permit, such as the removal or board-up of windows.”

The archdiocese has said the local Pilsen parish, St. Paul — which absorbed much of St. Adalbert’s congregation when it closed — decided “to remove and safeguard the stained glass after several break-ins and rounds of vandalism left some panes destroyed.”

The glasswork includes a rose window at the church entrance, windows throughout the nave and an intricate skylight above the altar.

The recommendation includes adjacent structures that are part of the St. Adalbert complex, including the Bartolomé de Las Casas Elementary School structure, and also allows for development on unused parts of the property.

The landmark recommendation is just the second step in an eight-step process toward a vote on landmark designation legislation by City Council. Next will be a report from the Planning Department on “how the designation affects neighborhood plans and policies,” according to the department of Planning and Development’s landmark designation process.

Strazzabosco said the entire process could take awhile — including several months for the commission to gather its materials and a few months for it to go through the City Council.

The likelihood that the parish of St. Paul won’t consent to the designation will also add some time as a public hearing would have to be held.

For the parish, the recommendation is an unwelcome development in its plans.

“The parish does not support it because it complicates the sale,” said Raul Serrato, a former St. Adalbert parishioner who now attends St. Paul. “Once it’s landmarked, it really complicates what you can do with that property.”

“We don’t want it torn down,” he said. “But there’s not a lot of people that want to come in and fix a former church, especially not one of this size.”

Serrato, a member of the parish finance committee, said the property is a “huge drain” on the parish finances, costing thousands of dollars a month in utilities and maintenance.

The parish first shut it because repairing it would cost an estimated $4 million, Serrato said, and after that, upkeep would cost around $20,000 a month.

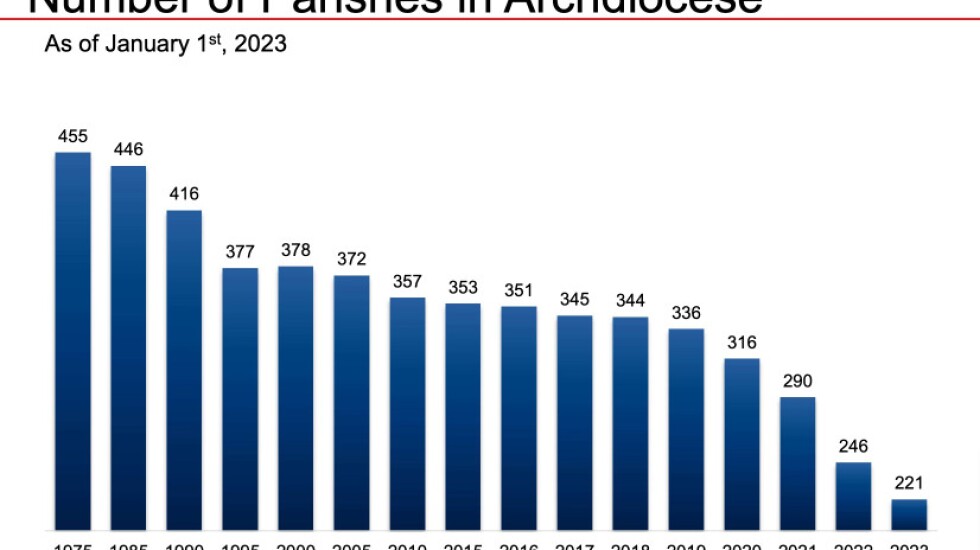

The church is just one of many that have closed in recent years since the archdiocese announced its Renew My Church initiative, a program to consolidate resources as the number of churchgoers falls. Between 2018 and the start of 2023, 115 parishes have closed, according to data from the archdiocese.

The recommendation has been long sought by a coalition advocating for its preservation, which includes former parishioners, architecture enthusiasts, local politicians and Polish cultural historians.

For months, they camped outside the church to block the removal of a beloved statue, which they viewed as an essential element of the building. That fight culminated in police detaining four of the protesters — and the statue was moved to St. Paul, at 2127 W. 22nd Place.

Among those supporting the commission’s recommendation was Judy Vazquez, a former parishioner, who grew up going to the Pilsen church and later became one its fiercest advocates to the point of being one of those detained by the police over the removal of the statue.

Her faith that the childhood church would get some respite, she said, was never shaken.

“We need to preserve history and heritage,” she said. “This is history in the making.”

After getting the landmark recommendation, a group of Polish supports voice their support with a brief song pic.twitter.com/fnppymgO4U

— Michael Loria (@mchael_mchael) August 7, 2023

Michael Loria is a staff reporter at the Chicago Sun-Times via Report for America, a not-for-profit journalism program that aims to bolster the paper’s coverage of communities on the South Side and West Side.