The spaces between stars in our galaxy are enigmatic realms filled with vast, diffuse clouds of gas and dust. These clouds tend to remain invisible — but the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has managed to capture one in a rare moment when it was lit up.

Peering at a dusty pocket of our galaxy about 11,000 light-years away in the constellation Cassiopeia, the James Webb Space Telescope's powerful infrared eyes watched as light from a centuries-old supernova illuminated interstellar material, warming it and causing it to glow.

"This is going to completely change the way we think about the foundations of the cold interstellar medium," Josh Peek, an astronomer at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Maryland, told reporters on Tuesday (Jan. 14) during the 245th American Astronomical Society (AAS) press conference in Maryland.

Remnants of the bygone supernova, which is the wreckage from the explosive death of a massive star, continue to captivate astronomers both for its striking beauty and science-packed complex structure. The collective supernova aftermath is famously called Cassiopeia A. Less famous, however, is the brief yet intense pulse of X-rays and ultraviolet light the dying star had pumped into space. The JWST witnessed the reflection of this light pulse as it bounced off the surrounding gas and dust while traveling through the interstellar medium — a phenomenon known as a light echo.

"Even with the resolution of JWST, you can't make out this beautiful 3D structure of these clouds until the echo propagates through," Jacob Jencson, a scientist at the California Institute of Technology, said during the AAS press conference. Because the light echo is powered by the supernova flash, studying it also allows astronomers to infer details about the star that exploded centuries ago, he explained.

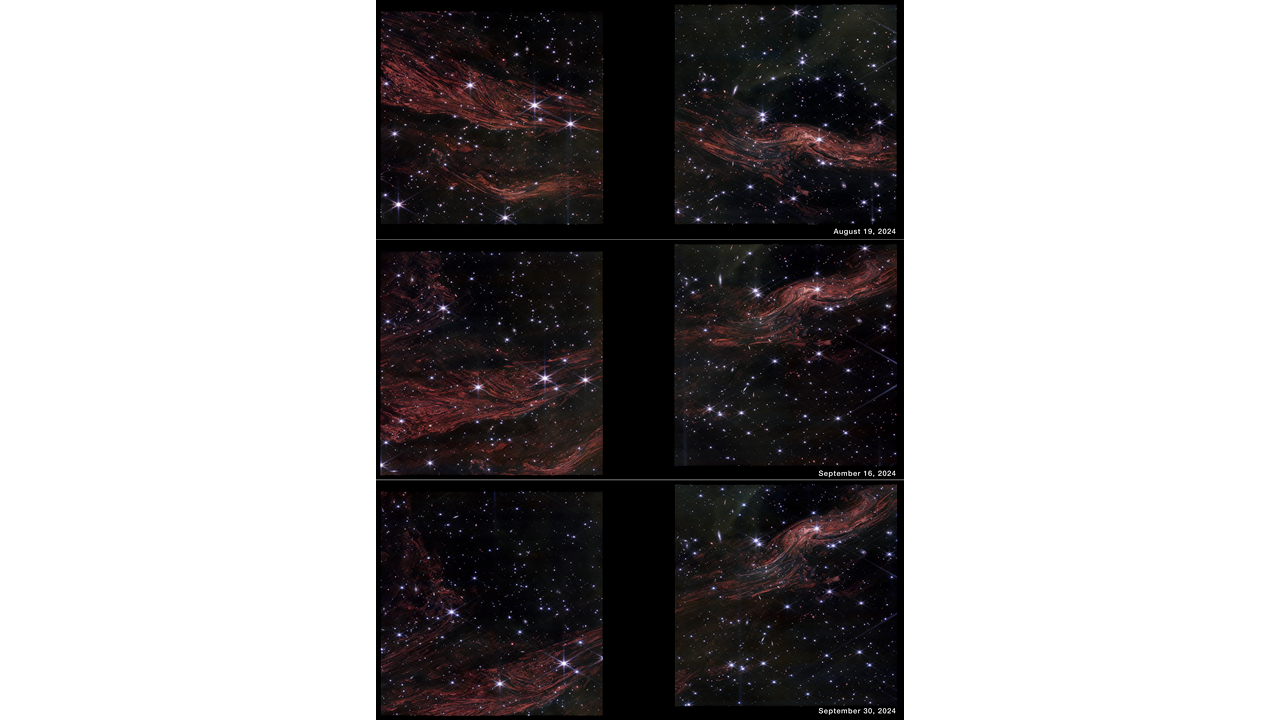

The newly released and exquisite images, which scientists describe as the astronomical equivalent of medical CT scans, have unveiled intricate, never-before-seen patterns in the interstellar medium. They include stunning snapshots of gas and dust morphed into sheets, which themselves appear to host structures on incredibly small scales, as well as isolated "magnetic islands" that resemble knots in a wood grain.

"We think every dense, dusty region that we see, and most of the ones we don't see, look like this on the inside," Peek said in a statement. "We just have never been able to look inside them before."

Scientists say these images will help them build a 3D map of these enigmatic structures, opening whole new regimes for studying the underlying physics of how such structures form and behave in the interstellar medium.

Of particular interest to the researchers are the magnetic knots, which likely play a role in how gas sheds its magnetic field — a crucial step for allowing gas to collapse and form stars, but one that is not fully understood.

"I've been studying the [interstellar medium] for a very long time, and mostly it is confusing," Peek said. "This has been a shockingly quick path to go from something you see that comes right off the telescope to something that is incredibly impactful in the sense of physics."