As the threat of a trade war escalates between the US and China, all the talk has centred on the tariffs that each side might impose on the other. But another important battleground is in Central Asia where both are fighting for strategic control.

Central Asia offers an array of economic opportunities for major powers, including access and control of valuable natural resources, favourable terms of trade and efficient trade routes. In seeking to shape the region, the US, China and Russia are all trying to regulate the international order in their image. The region might be more commonly associated with danger and security interests, such as Islamic radicalism, but what gets ignored is the region’s role as a strategic economic battleground.

Central Asia is at the centre of two new initiatives for regional economic integration by China and Russia that run against a longstanding economic vision of the US.

Russia’s Eurasian Economic Union (EEU), was established in 2015. It consists of Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Armenia, and is modelled on the European Union. There is free movement of goods, capital, labour and services, and common economic and industrial policies.

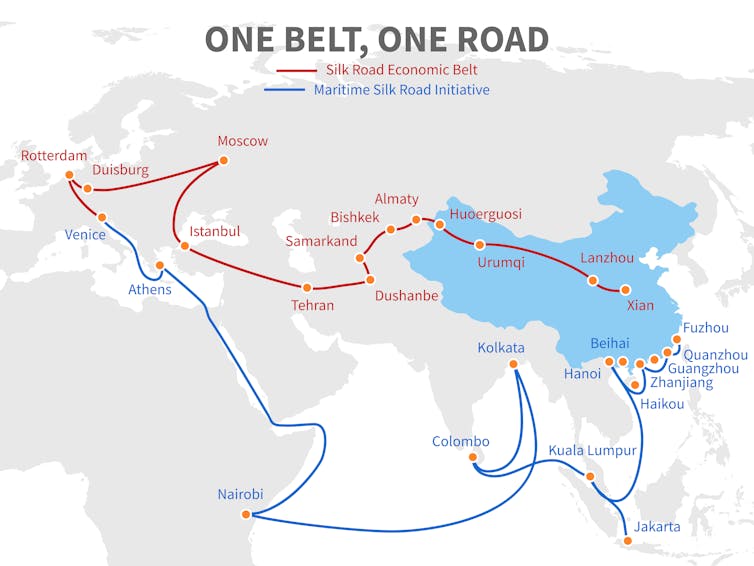

Second, China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) was proposed in 2013 and aims to create a trade and infrastructure network connecting Asia with Europe and Africa along ancient trade routes, such as the land and maritime Silk Road. Since then, many Central and South Asian countries have signed cooperation agreements with China to invest in energy and transport infrastructure.

Russia’s EEU and China’s BRI contrast with the dominant Washington Consensus model of free market economic thinking. This is promoted by US-backed international financial institutions, such as the International Monetary Fund. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, neoliberal reforms have been standard economic prescriptions in Central Asia and other parts of the world.

Different motives

These three ways of imagining the economic future of Central Asia are attempts by the major powers to address specific economic contradictions and crises at home. The US has been trying to open up other countries to its trade, investment and finance since its post-war economic model began to unravel in the early 1970s.

Russia’s strategy evolved in response to the devastating economic and political effects of radical neoliberal reforms (or “shock therapy”), which were implemented after 1991. China, meanwhile, has sought to invest its vast amounts of surplus capital into other countries’ infrastructure and productive projects, largely in response to fewer profitable opportunities at home.

Each economic strategy seeks a different outcome. The US and other Western countries want to extract wealth through the ownership and control of valuable assets, including natural resources and money.

In creating a customs union, Russia hopes to gain a competitive advantage over other trading partners, so as to protect its faltering industries. China wants to shorten delivery times and to access emerging markets.

Each great power has had varying degrees of economic success. Meanwhile, their political legitimacy has been weakened in different ways due to their negative effects in the region.

For instance, there has been a backlash of social discontent in Kyrgyzstan over foreign and elite acquisition of assets, predatory lending practices and household indebtedness. And, after entering the EEU, Kazakhstan experienced economic difficulties, resulting in strained relationships with Russia. In Tajikistan, some Chinese-financed projects have been embroiled in controversies over kleptocracy.

US upper hand

There are also various non-economic elements at play. Despite ethnic and religious differences, Russia’s EEU member countries have strong cultural, linguistic and symbolic ties because of their shared Soviet history. China, meanwhile, has reinvented the historical connections between China and Central Asia, by comparing the BRI to the Silk Road’s ancient network of trade routes.

But there are three reasons why the US is likely to be more successful than Russia and China. First, the US has considerable economic and financial resources to make cooperation beneficial for Central Asian elites. Recently Kazakhstan’s president Nursultan Nazarbayev met the US president, Donald Trump, and business leaders in Washington DC to appeal for more American investment and technology.

Secondly, the US also has the political and military power to sabotage its rivals’ plans. For instance, the US and the European Union were instrumental in pulling Ukraine away from Russia’s orbit. Without Ukraine’s participation, the EEU is considerably weakened. Plus, the US navy poses a threat to China’s trade routes through the South China Sea.

Thirdly, the US has been able to manage its economic contradictions and crises by drawing upon wider economic governing structures, including international financial institutions like the IMF and the World Bank. The US dollar as the world currency has also enabled the US to sustain an excessive military and consumer spending without undertaking austerity cuts.

The power that wins in Central Asia will shape the nature of global capitalism in the future and the economic and political crises the world will face. The 2007-08 global financial crisis, for example, showed how destructive and damaging American capitalism can be – and its full ramifications are still to be felt.

Since then, two alternative forms of economic arrangements have been built by Russia and China which could prevent history repeating itself. Inadvertently, Central Asia finds itself at the centre, as rival great powers seek to stamp their form of capitalism on the region and the world.

Balihar Sanghera was a George F. Kennan Scholar from September to December 2017. The authors are grateful to the staff at the Kennan Institute, Woodrow Wilson Center, Washington, D.C. for their generosity and support during their stay at the Center.

Elmira Satybaldieva does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.