‘The Anthropocene Museum’ by Cave Bureau is the sixth and final instalment in the family of exhibitions titled ‘The Architect’s Studio’ held at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Denmark. Since the series’ inception in 2017, visitors have been able to get to know international architects who are challenging the field at its core. Over the years, this has opened up a discussion, not only about where building culture is heading, but also what architects are able to work with, and how.

The final iteration of this theme, by the Kenya-based practice, is no different. Working at the boundaries of architecture, it is a quiet presentation of model, print and visual media loaded with social and cultural iconography; presenting a real cross-sectional view of the African condition as it begins to disseminate an approach towards a decarbonised and decolonised mode of operation.

Cave Bureau at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art

Taking nature as its starting point, ‘The Anthropocene Museum’ searches for an understanding of ‘Origin’ – or a return to origin. It begins by recording and analysing natural structures that are millions of years old; specifically, Mount Suswa in Kenya. The studio’s interest in an undocumented past (the mountain itself had never been documented through architectural drawings before) sets in motion thoughts about what merits recording in the history of architecture, and about the coexistence of architecture and nature. This new learning is then re-presented as a way of rethinking architectural discourse.

Using the cave as a springboard to narrate unrepresented histories of their own people and compatriots, Cave Bureau takes learnings from this research to reveal African notions of custodianship and care. The projects presented are gentle interventions in the landscape that support Indigenous people and the rhythms of nature while intending to relate to a modern Africa, and to heal fissures in the culture. The ‘Cow Corridor’, for example, is a restoration piece that seeks to reestablish the Maasai grazing routes through the capital Nairobi, which has been forbidden territory for cows since the British partition of the country.

Not simply a passive act of recording, many of the objects on display present an unavoidable confrontation with an uncomfortable past. The installation ‘The Door of No Return’ for example, is a version of the gate through which West African slaves passed before departing by ship to the Danish West Indies. Using stone sourced from a limestone quarry in Faxe, Denmark, it references the limestone found in the Shimone Caves of eastern Kenya.

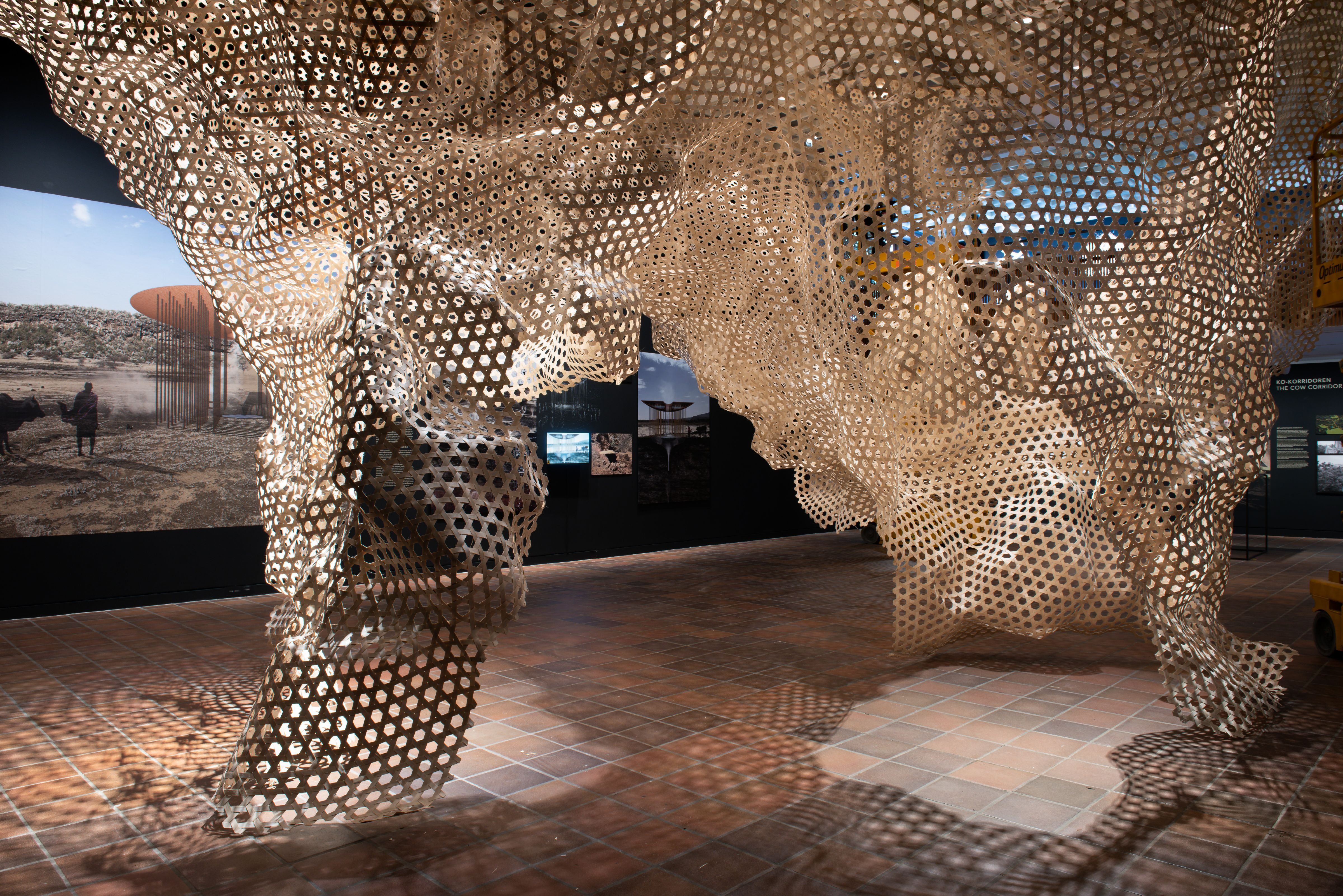

The exhibition culminates in an ambitious full-size attempt to reproduce the spatiality and materiality of the caves. Titled ‘Cave’ woven in rattan, it is inspired by pre-colonial craftsmanship and building techniques and is the result of a collaboration with The Centre for Information Technology and Architecture at the Royal Danish Academy in Copenhagen.

According to Cave Bureau founders, architects Kabage Karanje and Stella Mutegi, the architecture of the future must rely on knowledge of geology and connection to nature, as it traditionally has done in Africa. The architecture through which we have built our society in modern times and the way we view space, borders, cities and collective ties have to be reassessed by taking a critical stance towards anthropocentrism – the epoch within which our activity as humans on this planet has bred near irreversible shifts in our ecology.

‘Geology provides us with a tool to re-inscribe, to re-orientate and to relate to new ways of being on this planet; to realise that we are background,' says Karanje, director at Cave Bureau.

With re-orientation comes the potential for collective healing, and the potential of the continent to imagine its own future – to rewind in order to unpick and return with the appropriate knowledge that informs the now, and next.