The past 60 years have been a period of change and reflection for many in the Catholic Church, initiated by the Second Vatican Council in the 1960s and continued by the current synod on synodality.

In the autumn of 2021, Pope Francis announced a new synod, an official meeting of Roman Catholic bishops to determine future directions for the church globally. The first working document issued by the synod was published on Oct. 27, 2022.

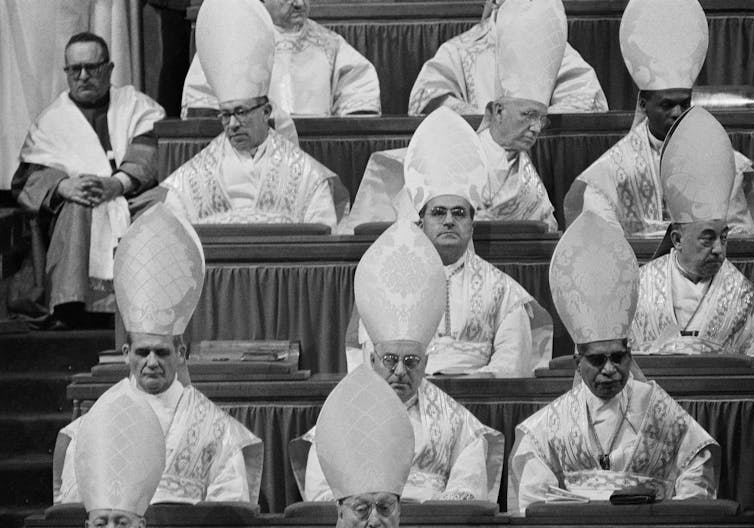

This document was made public soon after the 60th anniversary of Pope John XXIII’s 1962 convocation of the Second Vatican Council. During the three years that followed, Catholic bishops from across the globe met in several sessions, assisted by expert theologians. Many guests were also invited as observers, which included prominent Catholic laity and representatives from other Christian churches.

The council called for fresh ways to address 20th-century social and cultural issues and initiated official dialogue groups for Catholic theologians with others from different faith traditions.

However, Catholics have become increasingly divided over this openness to contemporary cultural changes. As a specialist in Roman Catholic liturgy and worship, I find that one important flashpoint where these deeper disagreements become more painfully visible is in Catholic worship, particularly in the celebration of its seven major rituals, called the sacraments. This is especially true in the celebration of matrimony.

Vatican II

In the mid-20th century, the church was still shaken by the repercussions of World War II and struggling to contribute to a world connected by the reality of global communication and the threat of nuclear war. Vatican II was called to “update” and “renew” the church – a process Pope John XXIII called “aggiornamento.”

One important theme connecting all of the council’s documents was inculturation, a more open dialogue with the variety of global human cultures. With the document Sacrosanctum Concilium, the bishops addressed the need to revisit the centuries-old worship traditions of Catholicism, reforming the structures of the various rituals and encouraging the use of vernacular languages during prayer, rather than exclusive use of the ancient Latin texts.

In the intervening decades, however, sharp contradictions and disagreements have arisen, especially over clashes between flexible cultural adaptation and rigorous moral and doctrinal standards. These have become much more visible during the past two pontificates: the more conservative Pope Benedict XVI – pope from 2005 to 2013 – and the more progressive Pope Francis.

The synod on synodality

For the present synod, Pope Francis began with a process of consultation with local church communities all over the world, stressing the inclusion of many different groups within the church, especially of those who are often marginalized, including the poor, migrants, LGBTQ people and women.

However, there has also been criticism. Some feel that the church should more swiftly adapt its teaching and practice to the needs of a variety of contemporary cultural shifts, while others insist it should hold on to its own traditions even more tightly.

Gay marriage

In North America and Europe, a major cultural shift has taken place over recent decades concerning gays and lesbians, from marginalized rejection to acceptance and support.

Over the years Pope Francis has come under fire for his comments about homosexuality. He has publicly stated that gay Catholics are not to be discriminated against, that they have a right to enter secular civil unions and that they are to be welcomed by the Catholic community. On the other hand, he has also refused bishops permission to offer gay couples a blessing.

Progressive bishops in Germany and Belgium, who had been proponents of this practice, organized an open protest by setting aside a day just for the bestowal of these blessings.

In contemporary Catholicism, discrimination or injustice against gay or lesbian individuals is condemned, because each human being is considered to be a child of God. However, homosexual orientation is still considered “intrinsically disordered” and homosexual activity seriously sinful.

The Vatican has warned progressives of the danger that these blessings might be considered, in the eyes of the faithful, the equivalent of a sacramental marriage. Some might assume that homosexual activity is no longer considered sinful, a fundamental change that conservative Catholics would find completely unacceptable.

This doctrinal perspective has led to other liturgical restrictions. For example, the baptism of children adopted by gay parents is considered a “serious pastoral concern.” In order for a child to receive the sacrament of Catholic baptism – the blessing with water that makes the child a Catholic Christian – there must be some hope that the child will be raised in the Catholic Church, yet the church teaches that homosexual activity is objectively wrong. Despite the current openness to gay Catholics, this conflict could lead to the child’s being denied baptism.

Following a document issued in 2005 under Pope Benedict XVI, Pope Francis in 2018 stated that candidates for the sacrament of ordination – the ritual that makes a man a priest – must be rejected if they demonstrate “homosexual tendencies” or a serious interest in “gay culture.” He also advised gay men who are already ordained to maintain strict celibacy or leave the priesthood.

Polygamy and colonialism

This recent cultural shift in Western nations has raised difficult questions for Catholics, both clergy and laity. In some non-Western countries, however, it is an older custom that has become an important issue.

The culture of many African countries is supportive of polygamy – more specifically, the practice of allowing men to take more than one wife. While the civil law in some countries might not allow for polygamy, the “customary law” rooted in traditional practice may still remain in force.

In some countries, like Kenya in 2014, civil law has been changed to include an official recognition of polygamous marriage. Some have argued that monogamy is not an organic cultural shift but a colonial imposition on African cultural traditions. In some areas, Catholic men continue the practice, even those who act on behalf of the church in teaching others about the faith – called catechists.

At least one African bishop has made an interesting suggestion. The openness to alternative cultural approaches has already resulted in one change. Divorced and remarried Catholics were once forbidden from taking Communion – the bread and wine consecrated at the celebration of the Catholic ritual of the Mass – because the church did not recognize secular divorce.

Today, they may receive communion under certain conditions. This flexibility might apply as well to Catholics in non-recognized polygamous unions, who are also not permitted to receive Communion at present.

As Pope Francis wrote in his 2016 document on marriage, Amoris Laetitia, some matters should be left to local churches to decide based on their own culture and traditions.

However, despite the need for increased awareness of and openness to diverse human cultures stressed during Vatican II and the current synod, this traditional custom is still considered a violation of Catholic teaching. Based on the words of Jesus in the Gospel of Matthew, Catholic teaching continues to emphasize that marriage can take place only between one man and one woman as a lifelong commitment.

How the current synod on synodality, in its effort to extend the insights of the Second Vatican Council, will deal with questions like these is still unclear. It is now set to run for an additional year, concluding in 2024 instead of 2023.

I served as a Catholic member of an official ecumenical dialogue group, the Anglican-Roman Catholic Consultation in the United States, for seventeen years.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.