To trace the spectacular fall from grace of Australia’s most decorated living soldier, Ben Roberts-Smith, VC, you may face a dilemma – which newly released book to read?

Nine investigative journalist Nick McKenzie, and his mentor, veteran investigative reporter, Chris Masters, have both written rival book-length accounts of their investigation into the fallen war hero.

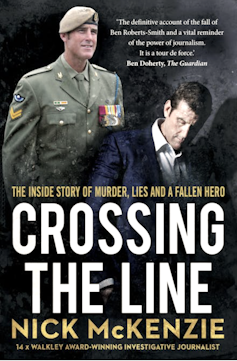

Review: Crossing the Line: the Inside Story of Murders, Lies and a Fallen Hero – Nick McKenzie (Hachette)

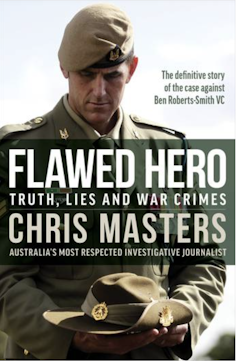

Flawed Hero: Truth, Lies and War Crimes – Chris Masters (Allen and Unwin)

Both McKenzie’s Crossing the Line: the Inside Story of Murders, Lies and a Fallen Hero and Masters’ Flawed Hero: Truth, Lies and War Crimes draw heavily from the duo’s collaborative reporting into Roberts-Smith’s military career and alleged war crimes in Afghanistan.

Finding themselves at the centre of a high-stakes, multi-million dollar defamation case, their stories are as much about Australian journalism as they are about the deadly transgressions of some Australian soldiers abroad.

In court, the pair relied on a defence of truth – a high bar when relying on confidential sources. Australia has among the toughest defamation laws of any liberal democracy.

This adds to the already difficult task of public interest investigative journalism, which seeks to unearth truths that those with power wish to keep hidden. It requires media organisations prepared to invest in this genre of reporting, and if necessary, spend millions to defend it.

This is a tough ask in a news media environment where the lion’s share of advertising revenues that fund journalism has shifted away from legacy media to online competitors such as Google and Meta. McKenzie knew:

It was vastly cheaper to settle and apologise than to fight, even when a paper had it right.

Yet, despite these tough times, the journalists had their employer’s backing.

As Masters reminds us, watchdog reporting is different to everyday reporting.

Investigative journalism is resource intensive and subject to eternal budgetary pressure.

It also takes time – in this case, more than six years. Now, with Roberts-Smith announcing he will appeal, the end is unknown. In any case, “the burden stays with you, often well beyond publication,” writes Masters.

‘Dry-retching from stress’

McKenzie, a 14-times Walkley award winner, confides that over his investigative career he’s thought of quitting. He admits there were days in the bathroom “dry-retching from stress”. Add to that, “war crimes were notoriously hard to investigate, even for police.”

Big obstacles, outside their control, conspired against their fact-finding. The resurrection of the Taliban made it hard to reach Afghan witnesses; COVID lockdowns made travel to investigate claims and bring witnesses to a Sydney courtroom tricky.

A tribal media, terribly divided, meant News Corp and Seven West Media gave Roberts-Smith glowing coverage. More curiously, Masters writes his former ABC Four Corners investigative journalism colleague Ross Coulthart was commissioned by Channel Seven’s commercial director, Bruce McWilliam, to “interrogate our work”.

Coulthart claimed to have evidence that would vindicate Roberts-Smith. Masters reports that after Coulthart cancelled a meeting with McKenzie, he undermined the journalists by texting their boss, Nine’s group executive editor James Chessell, and offering to “help fix a looming disaster for him and the paper.” Chessell was not swayed.

In a further display of the raw power of money, and of media mates backing Roberts-Smith, Seven’s owner, Kerry Stokes, gave him an executive job at Seven and footed his massive legal bills.

A central theme of both books is trust, and with it, truth. With some of Seven’s stories painting Roberts-Smith as a hero, and directly targeting Masters, why should the public trust these two journalists, or any for that matter?

The media wars left Masters musing:

Who would have anticipated that my opponents would be neither the government nor the Defence Force, but a constellation of friends, fellow journalists and a television network?

And how could key sources, such as brave SAS comrades troubled by what they had experienced on their deployments, trust anyone with their story, let alone reporters? Especially, as theirs is a culture that demands secrecy and condemns those who speak ill of mates. These were giant hurdles McKenzie and Masters – and a few other talented colleagues at the ABC and Nine whose reporting added pieces to the puzzle – would overcome.

‘Bloodings’ and ‘throwdowns’

On the brink of a merger with Fairfax media in 2018, Nine Entertainment proved doubters wrong, backing its investigative reporters. With this institutional support over six years, McKenzie and Masters’ front-page stories in The Age, Sydney Morning Herald and Canberra Times, with special TV reports for Nine’s 60 minutes, alleged a very dark side to Roberts-Smith, exposing a broken culture within the Special Air Service (SAS) Regiment.

Roberts-Smith maintained he was a target of smear and lies because of jealousy over his medal success and hero status.

At the outset, Masters (like McKenzie) seriously considered “the proposition that some allegations might be driven by fear and loathing, rather than fact and logic, couldn’t be discounted”.

Prior to their investigations, rumours and allegations had been swirling about cruel and unlawful acts within the Australian special forces. These led to The Inspector-General of the Australian Defence Force Afghanistan Inquiry; also known as the Brereton report.

In 2020, that four-year inquiry, which examined a time period from 2005-2016, concluded there was “credible information” that outside the heat of battle, 39 individuals were unlawfully killed, a further two cruelly treated, and a total of 25 current or former ADF personnel were perpetrators. It added credence to Masters’ and McKenzie’s reportage these were not “fog of war” incidents and cast a long shadow over Roberts-Smith’s jealousy theory.

McKenzie’s and Masters’ evidence extended beyond a reliance on interviews, combining these with covert audio records, metadata of photographs from the front line, official documents, the journalists’ own observations of interviewees and informants over time, and more. In their books, they add the transcripts of court proceedings.

Given they worked so closely together, unsurprisingly their books are similarly structured, with a consistent and disturbing narrative about unlawful conduct in Australia’s longest war.

They introduce us to a lexicon of egregious acts consisting of “bloodings” (a rookie’s first kill ordered by a superior); “throw downs” (placing incriminating evidence on a dead body); “kill counts” and “drinking vessels” (such as the trophied prosthetic leg of a dead Afghan).

Both focus on Roberts-Smith’s striking physique (he is more than two metres tall) and Jekyll-and-Hyde character – charismatic and charming, but also a “frilled-neck lizard” if angered (as one detractor described him to Masters). But at the centre of their stories is the unlawful killings, as found by the Federal Court.

At times, they relay the same quotes and anecdotes, begging the question: why didn’t they continue the partnership? Masters’ in part answers that, writing:

Nick and I worked well together as investigators, but regrettably could not co-ordinate the writing. We did try.

For his part, McKenzie speaks of a past falling out: “We’d had a bust-up over secrets,” but with the tincture of time attributes it to “mixing two fiercely focused journalists with their own inbuilt securities.”

Looked at another way, one can understand the catharsis of writing a personal account after such a long, hard journey. Investigative reporting is incredibly challenging and can be a deeply lonely experience. When I interviewed Masters in 2011 about his famous Moonlight State investigation in Queensland in the 1980s, which exposed systemic police corruption, he told me:

It is easy to get really angry with how lonely you feel when you are in a big fight that goes on forever, and it seems that so often you have to wear most of it on your own.

Tough stories demand you put your life on hold, especially if you are facing legal action, which of course McKenzie and Masters were (with colleague David Wroe). But, this lawsuit trumped all others, labelled the “defamation case of the century”.

Days before the verdict, many feared for investigative journalism’s future. With court costs above A$25 million, media academic Tim Dwyer told The Guardian a loss would

have a chilling effect on investigative journalism on all media organisations who pursue these kinds of very consequential public interest stories.

He was right to be worried. While globally, investigative journalism has adapted to the age, parsing big data, utilising cross-border collaborations (such as the Panama Papers) and diversifying its funding to survive; in Australia’s concentrated media market, legacy media still pay most investigative journalism bills.

Masters, a rare breed as an underpaid freelance investigator and an Australian Media Hall of Fame inductee, notes that “the digital age was steadily eroding what was left of the traditional revenue base for important news journalism”.

Read more: Why investigative reporting in the digital age is waving, not drowning

Moral order

Days later relief struck. The Federal Court’s Justice Anthony Besanko found against Roberts-Smith. Masters’ and McKenzie’s legal team had established the substantial truth that the former SAS soldier had committed war crimes.

Among them, was that Roberts-Smith had killed an Afghan man who had a prosthetic leg at an insurgent stronghold known as Whisky 108, and kicked a farmer from near the village of Darwan, Ali Jan, off a cliff, before ordering another soldier to shoot him.

“I find that the applicant was not an honest and reliable witness in the many areas I will identify,” Justice Besanko wrote in his 726-page judgement.

Investigative reporting involves questions of moral order. It gives the voiceless a voice – like Ali Jan. It differentiates between victims and villains. This long investigation had plenty of both. It also has some quiet heroes.

Both journalists identify special people who “put principle and moral institution first” as Masters describes it. Among them were former SAS captain turned politician Andrew Hastie; Age journalist and mentor to McKenzie, the late Michael Gordon; Nine’s lawyer, the late Sandy Dawson SC, and the sociologist who first lifted the lid on the SAS’s excessive, unsanctioned violence in a secret Defence Department report, Samantha Crompvoets.

To compare the two books is somewhat pointless. Both are well-written and substantial (Masters’ just over 500 pages, McKenzie’s just under). Naturally, there are points of difference in style. Masters walks the reader through greater detail of some events with more personal contemplation – perhaps reflecting the different stage of his journalism career, and his deep knowledge of soldiers’ dispositions and army culture, acquired when he was embedded in war zones.

McKenzie artfully uses literary devices, such as first and third person narratives, to weave together multiple threads. These cover matters such as the progress of the investigation, the unfolding court room drama, and the personal toll of more than six years of painstakingly putting together the pieces to show a necessary, but ugly, truth.

A key, and somewhat distracting difference, is Masters is more reserved in naming names than McKenzie. He insists on using pseudonyms that can become confusing given the long list of characters in this story.

Both Masters and McKenzie knew from hearing Roberts-Smith’s voice on covert tapes leaked by a source that his “greatest hate” was reserved for them. “On the tape he made it clear he would do anything to bring us down,” McKenzie writes.

Investigative reporting is an extraordinarily stressful job, and McKenzie reveals throughout his book his battle with controlling his anxiety. Masters, for his part, is more understated, “being sued is not fun,” he writes, and being a freelance investigative reporter is a tough way to make a living:

For a freelance investigative journalist like me, the deal is a miserly one. We get the conventional dollar a word rate, irrespective of the time and effort applied.

War has always been the stuff of myth-making from the Anzacs to the present day. Both books shake the blind beliefs of those who unquestionably only see what they want to see – a war hero.

Of course, life is rarely that simple – and McKenzie colours in the outlines to show a deeper reality, with all its hues, concluding that a man recognised as a war hero, could also be described as “a war criminal, a bully and a liar.”

Read more: What should the Australian War Memorial do with its heroic portraits of Ben Roberts-Smith?

Questions

After finishing the two volumes, questions linger. How did the most senior ranks of the Australian military not know what was really going on?

How did the politicians who sent the same soldiers on multiple, lengthy missions to Afghanistan to risk suicide bombers and green-on-blue-attacks from men wearing Afghan uniforms, not think such exposure might recalibrate a soldier’s moral compass?

Masters gives us some insight:

With special forces, secrecy was encoded, along with a bias for offensive action.

Both books will appeal to a general audience, but also specifically to academics, students and practitioners of journalism with their contemplation of what it is to be an investigative journalist in uncertain times for Australian news media. They show the salves of truth-telling, an independent judiciary and investigative reporting’s role in democratic accountability.

It must be remembered that Roberts-Smith continues to maintain his innocence, and is appealing the Federal Court decision. So for both McKenzie and Masters, the story is not over.

As to the opening dilemma? My advice is to read them both.

Andrea Carson is a member of the research committee of the Public Interest Journalism Initiative (PIJI) and author of Investigative Journalism, Democracy and the Public Sphere (2020). She was previously a journalist with the Age (1997-2001) and radio producer at ABC Melbourne (2004-2010).

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.