Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised that the following contains information about deceased persons, ceremonial practices, and Men’s and Women’s Business with the permission of the Gaanha-bula Action Group.

People have long used symbols (marks or characters) to communicate ideas and concepts. It is something that sets humans apart from other beings.

The oldest dated example of symbolic thinking is a 77,000-year-old carved ochre object found in South Africa. While we will never know what its symbols meant, it is a different story in Australia, where we are privileged to learn from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples today about symbols made by their ancestors in the past.

One remarkable example of symbolic expression is the marara (carved trees or dendroglyphs) of Wiradjuri Country, in southeastern Australia. In a new Wiradjuri-led study, we have combined traditional cultural knowledge and archaeological methods to develop culturally and scientifically informed understanding of these sacred locations for the first time.

Our study of marara and dhabuganha is guided by the principles of the Wiradjuri philosophy Yindyamarra (cultural respect).

Carved trees and burials

Marara are trees with elaborate muyalaang (tree carvings), marking the dhabuganha (burials) of Wiradjuri men of high standing. They represent a traditional cultural practice with deep roots.

Wiradjuri people created marara by removing a large slab of bark, then intricately carving muyalaang into the fresh tree surface. Muyalaang often appear as a series of curved lines or geometric patterns like diamonds and zig-zags.

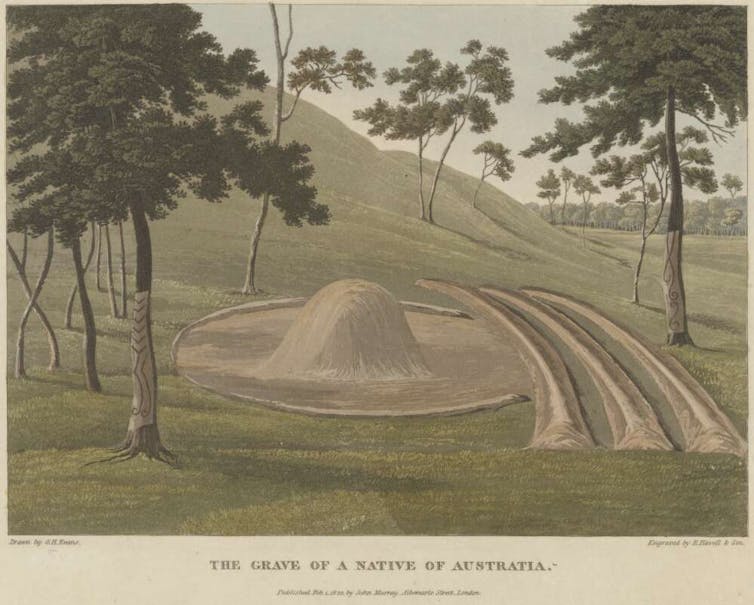

The British explorer John Oxley described marara and dhabuganha in an 1817 diary entry. Three years later, painter G.H. Evans depicted the scene, with several marara carved to face a central dhabuganha and three “mourning” seats:

The form of the whole was semi-circular. Three rows of seats occupied one half, the grave and an outer row of seats the other; the seats formed segments of circles of fifty, forty-five, and forty feet each, and were formed by the soil being trenched up from between them. The centre part of the grave was about five feet high, and about nine long, forming an oblong pointed cone.

Today, a diminishing number of marara remain. Most dhabuganha are no longer visible due to erosion and modern land-use practices.

Two burial sites

We used ground-penetrating radar at one location to non-invasively analyse and map changes in soil to refine our understanding of the resting place of a Wiradjuri man of high standing, whose dhabuganha is no longer visible today but remains marked by a marara. We created a 3D model of this marara.

Not far away, on the other side of a creek, is a fallen scarred tree reported to mark the dhabuganha of the man’s “wife”. The man’s marara and the woman’s fallen scarred tree would have faced each other when the fallen tree was still standing – perhaps as a symbol of their connection.

We also studied marara and dhabuganha at Yuranigh’s Grave, a public tourist site near Molong. Yuranigh was a Wiradjuri man of high standing who accompanied explorer Thomas Mitchell on his inland expeditions during the 19th century.

Mitchell valued Yuranigh so much that, after Yuranigh’s passing, he added a European headstone to Yuranigh’s dhabuganha, which is also surrounded by several traditionally carved marara. The headstone inscription reads:

To Native Courage Honesty and Fidelity. Yuranigh who accompanied the expedition of discovery into tropical Australia in 1846 lies buried here according to the rites of his countrymen and this spot was dedicated and enclosed by the Governor General’s authority in 1852.

A bigger cultural landscape

Despite the remarkable appearance of marara, our interviews with Wiradjuri Elders and knowledge holders make it clear that marara are not just artistic objects. They are sacred locations with specific cultural (or symbolic) meaning that is not clear without deeper understanding of Wiradjuri people and Country.

Wiradjuri Elder Uncle Neil Ingram reveals that muyalaang speak to “the different clan groups and their stories”. Wiradjuri Elder Aunty Alice Williams explains that muyalaang are “connected back to the totems” of the area. Wiradjuri Knowledge Holder James Williams states that marara show “a path from here – this life – to the next life”, between the earth and “sky world” where Baiame the Wiradjuri Creator, or Sky Spirit, lives.

Our interviews with Wiradjuri Elders and knowledge holders also highlight that marara and dhabuganha should not be understood as individual locations or isolated “sites”.

Wiradjuri Elder Aunty Alice Williams explains that “you need to open your mind and think further than what’s on the tree, and what’s in the ground, and have a look around, and see what’s there … within a bigger cultural landscape”. Marara and dhabuganha form part of a connected system of Wiradjuri lore, beliefs, traditional cultural practices and Country that involved men, women and children together.

Marara and dhabuganha encourage us to look beyond what we perceive in physical form to understand the different ways of seeing the world around us.

We have had the privilege of working together to document these sacred locations, and to shine a light on this important and fragile part of Australian history. Marara and dhabuganha tell a hidden story that is not apparent without deeper cultural understanding.

The authors wish to acknowledge this article was also written with Uncle Neil Ingram (Wiradjuri Elder), Aunty Alice Williams (Wiradjuri Elder), James Williams (Wiradjuri Knowledge Holder), Yarrawula Ngullubul Men’s Corporation, Orange Local Aboriginal Land Council, Michelle Hines (Central Tablelands Local Land Services) and Tracey Potts (Central Tablelands Local Land Services).

Caroline Spry undertakes research at La Trobe University and receives research funding from La Trobe University and government.

Brian J Armstrong receives funding from the University of Melbourne and the Australian Research Council.

Greg Ingram works for the Central Tablelands Local Land Services.

Lawrence Conyers receives funding from the University of Denver.

Ian Sutherland does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.