Australian photographer Carol Jerrems took an expansive approach to portraiture. She experimented with seriality – constructing narratives and meaning across multiple frames – and understood photography as a collaboration between her subjects, her camera and herself.

Born in Ivanhoe, Victoria, in 1949, Jerrems worked primarily with black and white photography until her early death in 1980.

Over 140 of her photographs are currently on display at the National Portrait Gallery in Canberra.

Everyday scenes, collective portraits

Faces are just one element of Jerrems’ portraits. Equally significant are the spaces she chose to photograph.

Many photographs depict her subjects in everyday realms: bedrooms, living rooms, suburban backyards and streets in Melbourne and Sydney in the 1970s.

She focused on faces and bodies amid the rumpled sheets of a bed, the clutter of a room, suburban street signage, the drape of a hospital curtain – always attentive to the interior frames of windows, tables, doorways.

Many images are taken in spaces dedicated to creativity or protest, speaking to the feminist politics of 1970s Australia and the mesh of domestic life, creative labour and resistance. There are artists’ studios, protests, the Filmmakers Co-Op in Sydney and the National Black Theatre in Redfern. There are film reels and fridges, sewing machines and slogans.

There are scenes at a university campus (a commission for Macquarie University), and eventually, and with finality, the interior of a Hobart hospital in the last series before her death from the rare illness Budd-Chiari syndrome in 1980.

These environmental portraits position the subject in a familiar context, such as their workplace or home. They treat space as part of the complexity of her human subjects.

This is not to say faces, and individuals, are not key: they are everywhere in this exhibition. Some are well-known, others are not.

Many of the portraits in the exhibition are photographs taken as part of Jerrems and Virginia Fraser’s 1974 photobook, A Book About Australian Women.

The book collates photographs of children, activists, writers, artists, historians and sex workers. There are the recognisable faces of a young Evonne Goolagong (1973) and an elderly Grace Cossington Smith (1974).

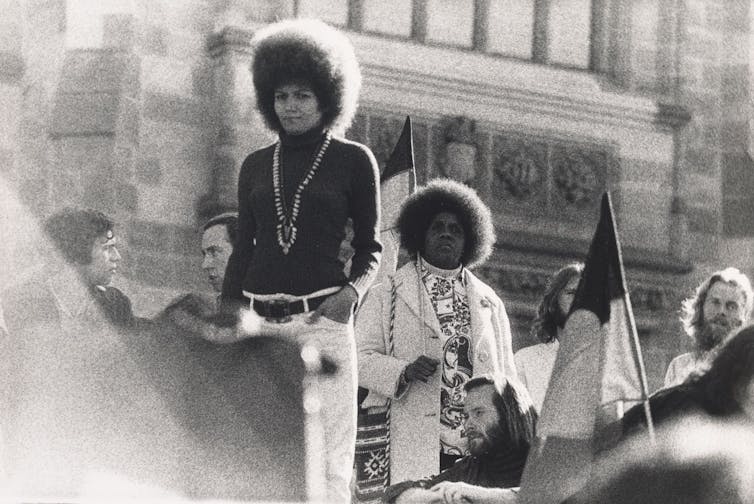

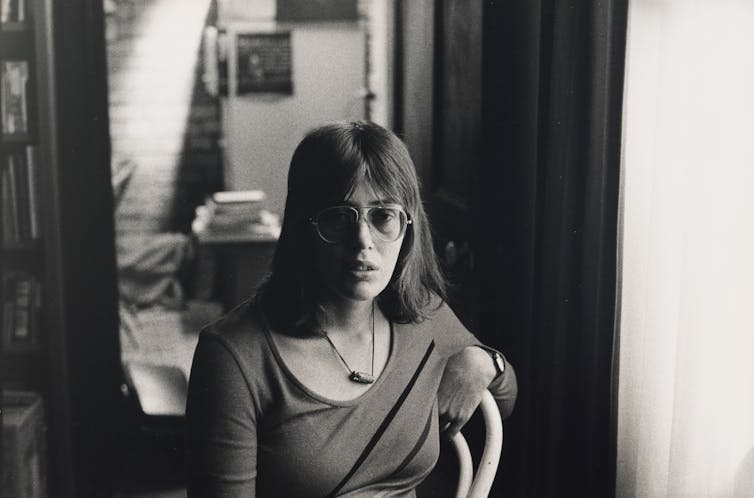

Portrait of Anne Summers (1974) pictures the author in her home, half her face in shadow, a pile of books behind her. Bobbie Sykes is at the podium in Black Moratorium, Sydney ’72 (1972) and elbows jutting out, hands on hips looking away from the camera in Bobbi Sykes, Aboriginal Medical Service (1973).

Shadows, patterns, frames

Looking at photographs can bring the temptation to focus on the singular, to seek out the one image that “speaks”.

But Jerrems’ life work, and the curation of this exhibition, suggest a different project. The meaning here accumulates across and between images.

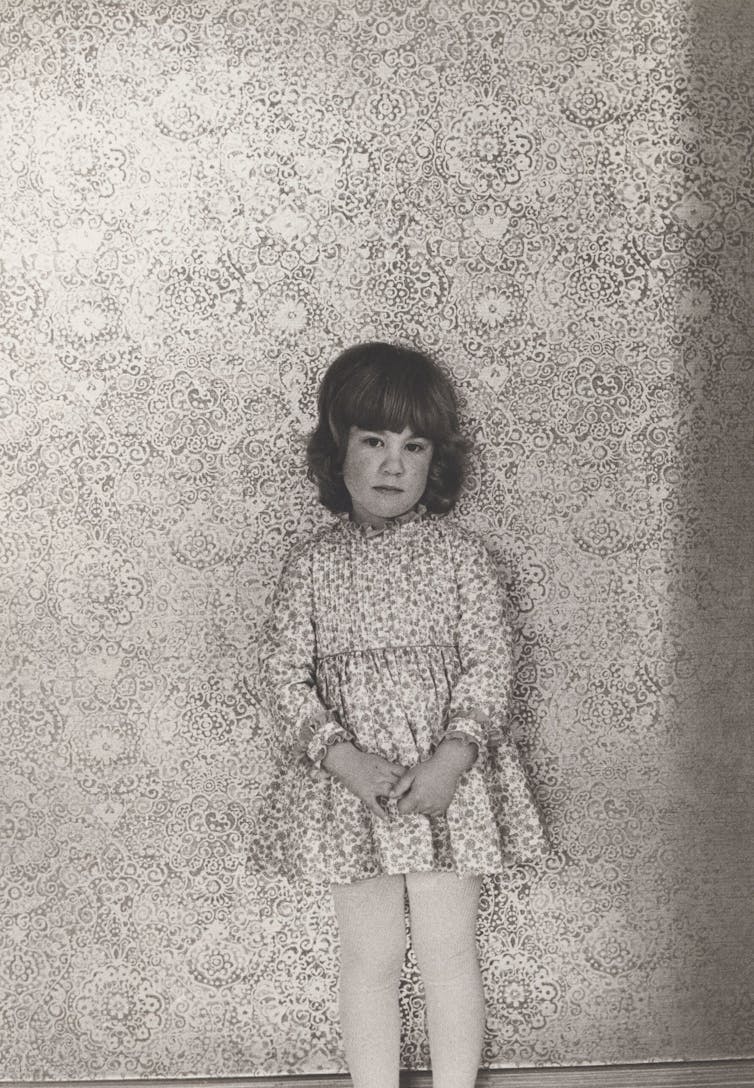

The photograph Caroline Slade (1973) pictures a young girl, a solemn chameleon in a floral printed dress surrounded by floral wallpaper. This moment of camouflage has echoes in the image Enid Lorimer and Kate Fitzpatrick (1974). This photograph shows the actors gazing at each other in floral dresses that merge with the patterning of leaves in the garden behind them.

Sites of mimicry are coupled with other patterns, other photographs in conversation. Shadows repeat across images and years.

Lynn Gailey sewing (1976) features the right half of Gailey’s face in shadow. In the earlier photograph of Myra Skipper (1974), the bottom half of her face is in shadow and her eyes are averted upwards. Esben Storm’s face, repeatedly held by Jerrems’ gaze, regularly emerges from shadow, dappled with light.

Cuts, exchanges, phases

There is an autobiographical bent to many of the portraits. Jerrem’s presence enters the frame of Rita on the couch at Kilcare Beach (1976). The shadow of Jerrems’ arm, holding camera to eye, mirrors the angle of Rita’s crossed limbs.

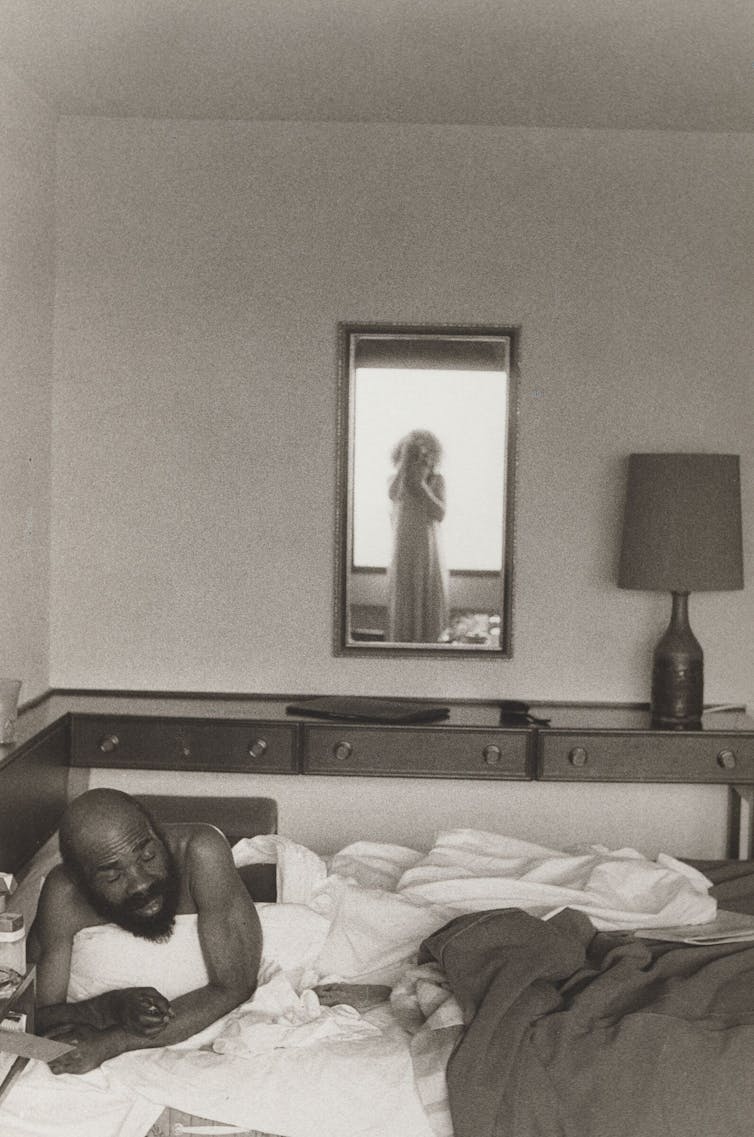

Jerrems’ photograph of Ambrose Campbell (1973) shows him relaxed on a bed covered in white sheets. The photograph is framed to include her mirrored reflection, dressed and standing camera to eye. She is composed and appears distant, framed by the bright light of the window behind her.

In Self portrait after surgery (1979) Jerrems pulls the photographic frame in tightly around herself, her elbows raised but her camera and face are out of frame. There is a long stitched incision down her abdomen, the bruises and residues of medical tape telling a story on her skin.

In 1969 Jerrems produced the handmade, accordion photobook A Continuum of Age as an assignment while a student at Prahran Technical College.

In the front of the book strips of cut-and-pasted typewriter text explain the relevance of age to “every speck of matter”. The photographs compiled in the book are “not concerned with individuals, but with states, with phases, with specific periods of existence”.

This conceptual framing of the photobook (which, wonderfully, is on display, splayed open behind glass) offers another entry point to understanding Jerrems’ work and portraiture made during the following decade.

The photographs in this exhibition are all small prints, intended to be looked at closely, and, crucially, in relation to each other. This approach is reflected in the decision to exhibit several of Jerrems’ contact prints – sheets containing grids of images – which reveal their own history of being held, written on, cut into.

These imperfections are themselves part of the photographic exchange. They reflect the chain of decisions made by Jerrems, a glimpse into her process.

Carol Jerrems: Portraits is at the National Portrait Gallery, Canberra, until March 2.

Jane Simon does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.