Long before Jed Mercurio was celebrated as the man behind dark police corruption drama Line of Duty, he made his name with another equally brooding show: Cardiac Arrest, which aired on BBC1 in the mid-1990s. Written (under the pseudonym John MacUre) when Mercurio was still working as a junior doctor at Drumchapel hospital in Glasgow, the series follows a group of sleep-deprived, stressed-out junior doctors as they cope with everything from bullying consultants and officious managers to surly nurses and patients too sick to save.

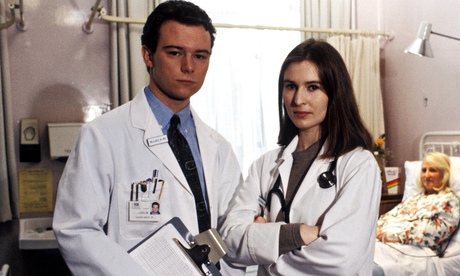

“Prolonging a patient’s death isn’t the same as prolonging his life,” the ice-cool Dr Claire Maitland (a career-best performance from Helen Baxendale) tells the wide-eyed and religious Dr Andrew Collin, in the first episode. Cardiac Arrest’s greatest strength comes from that clear-eyed acknowledgment that the realities of medical life are very different from the airbrushed portrayals we see on most medical shows.

For a measure of how groundbreaking it was, you need only to compare it with another medical drama that began at the same time: ER. Where the long-running US drama’s protagonists were generally shown to be right even when they initially got the diagnosis wrong, Cardiac Arrest was unflinching in its depiction of a world where errors could – and did – happen. Thus in the second series, a memorably gruesome scene saw the competent Claire failing to save a haemophiliac patient from dying of a nosebleed because she wasn’t trained in ENT (Ear, Nose and Throat). The BBC was obliged to issue a statement the following week assuring viewers that deaths from nosebleeds were rare in real life.

It wasn’t the only time Cardiac Arrest broke boundaries and caused controversy. In the first series, Claire was shown upping a dying patient’s painkillers to bring about a merciful death, while the second series was notable for ward consultant Mr Turner’s neglect of his duties, which led a junior doctor to send a patient into analeptic shock. Most harrowing of all was a plotline following Dr Monica Broome as she desperately juggled motherhood with the demands of her job as a surgeon, even as her vicious supervisor bullied and sexually harassed her.

The show was forthright on matters of race and sex, too. Bisexual anaesthetist Dr James Mortimer struggles to keep his job in the light of an HIV diagnosis (a subject very much in the news then) while the seemingly laidback Dr Rajesh Rajah battles both his parents’ desire for an arranged marriage and the institutional racism of his profession. In the third season, when Rajah is passed over for a GP training scheme, consultant Adrian DeVries nonchalantly explains that “doctors with foreign names never get the nod”.

But if Cardiac Arrest had only been about stress and symptoms, it would never have had widespread appeal. Instead, the show regularly drew around eight million viewers – many of them members of the medical profession who hailed Mercurio’s accurate depiction of hospital life. Certainly, his intimacy with his subject meant that he understood its gallows humour: the cremation forms referred to as “ash cash”, the dark jokes about the dying, the small defence mechanisms and practical jokes that get you through long days and nights treating patients with no more than 30 minutes sleep.

Watching it again on DVD, it’s that sense of shellshock – of the junior doctors as walking wounded – that’s so powerful. There are moments that have dated (the brick-like mobile phones, the crafty fag breaks in empty offices) and it occasionally tips into caricature, portraying a world of unhelpful sex-obsessed nurses (the Royal College of Nursing complained) and arrogant, largely absent consultants (they complained too) with the under-qualified junior doctors keeping the whole ship afloat.

Yet those caricatures come in part from anger and it’s this that gives Cardiac Arrest its power. It ended prematurely – and on a cliffhanger with Claire trying to save Andrew’s life following a patient attack – when Baxendale, fearing typecasting, refused to sign up for a fourth season, while Mercurio’s own career hit an upward path. After writing nostalgic Midlands comedy The Grimleys, he returned to medicine in 2004 with the coruscating Bodies, which delved deep into medical malpractice, before creating Line of Duty in 2012. His third medical drama, Critical, has just started on Sky. Will it see him striking gold again? Probably, especially as Line of Duty suggested he hasn’t softened over the years. But the dark honesty and uncompromising humour of Cardiac Arrest still make it the one to beat.