A version of this story ran in the March/April 2021 issue.

More than most Westerns, News of the World is about things which no longer are. Where most entries of the genre take a broader view of the West and its iconography, Paul Greengrass’ latest feature relishes in the historical specificity of Texas in 1870. It’s a world drained by the exhaustion of the Civil War but also hopped up on the lawlessness of Westward Expansion. The United States is turning a page in its own history and those who can’t keep up are sure to be left behind. The film’s focus is on the chaos of change, which is also, unfortunately, where it loses its way.

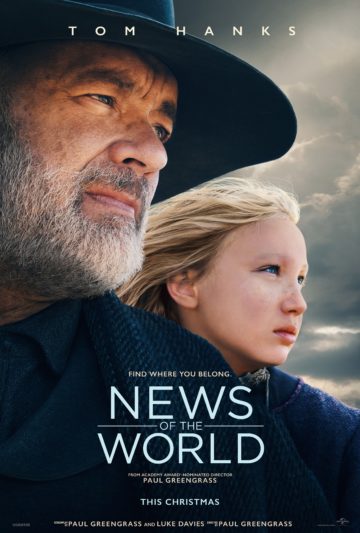

In Wichita Falls, we’re introduced to Captain Jefferson Kyle Kidd (Tom Hanks), an ex-Confederate from San Antonio who makes his way by traveling town to town reading current events from newspapers to illiterate locals at 10 cents a head. He draws modest crowds, but his profession is quickly becoming antiquated. He’s a man haunted by his own history, constantly on the move to escape his memories of war and his wife’s death. While traveling to his next town, he comes across the site of a wagon massacre. The initial assumption is that it was an Indian raid, but Kidd soon discovers the lynched body of the Black driver tagged with a racist warning. At the site of the attack, he also finds a white girl (Helena Zengel) clad in buckskin who only speaks Kiowa. Johanna is an 11-year-old white captive recently retrieved by the lynched driver to be returned to her family. After an unsuccessful hand-off to Union Army officials, Kidd, with Hanks’ signature All-American grit, takes it upon himself to return her.

From there, it’s a largely by-the-numbers captivity narrative, as the pair weather a treacherous odyssey in search of her family by way of the elements, marauders, and witness landscapes on the brink of monumental historical change. An enduring storyline in the Western genre, captivity narratives center the experience of white settlers captured by Indigenous people, their time among them, their rescue and eventual return. It’s a heavily romanticized form rooted in colonial anxieties of Indigenous peoples and animated by fears of miscegenation. To his credit, Greengrass knows what he’s working with. Rather than delivering on the expected Native American as pursuant hostiles, the film focuses on a mix of other villains: a gang of ex-Confederate human traffickers and then later a boomtown militia led by a corrupt buffalo hunting tycoon.

But that subversion contributes to the film’s numerous false starts and sluggish feel. The human traffickers are taken care of in a tense shootout, and later the tycoon, through one of Kidd’s newspaper readings that riles up the illiterate militia to unionize and turn on their boss. It’s a heavy-handed sequence, and possibly the only time reading has been used as a weapon in a Western, but it’s also key to what the film is getting at. News of the World prides itself on its earnest belief in literacy as an American value and something that can ultimately save the nation from itself. It’s a simplistic and somewhat naive view, considering it’s provided as a counter to the fallout of the Confederacy’s ideologies and ecological collapse of the Plains at the hands of unchecked capitalism. It’s also a trademark Tom Hanks vehicle. Whether he’s Captain John H. Miller surviving D-Day in Saving Private Ryan, or the titular Captain Phillips navigating a terrorist hijacking, Hanks embodies an inherent decency and optimism for the nation’s spirit. Even when his mettle is tested, better days are just around America’s corner.

When it comes to the captivity narrative itself, the film self-consciously tries to subvert expectations of where Indigenous people lie within this tried and true formula. By centering historic examples of white supremacy as the story’s driving forces, News of the World proposes a reconsideration of how the captivity narrative historically posits savagery in the West. Despite himself being an ex-Confederate, Kidd is an apolitical figure and his ability to read and interpret the written word distinguishes him from the knuckle-dragging heavies he encounters. They’re presented as unkempt hicks driven by a lust for violence and capital, too thick to see their own exploitation at the hands of their superiors.

The Achilles’ heel of News of the World is its own tip-toeing around how to handle the presence of Indigenous people in a reframed captivity narrative. Save for a few mentions of dissolution of Indian Territory, it funnels these concerns into the obvious surrogate that Johanna presents. She may be the blonde-haired, blue-eyed child of German settlers, but she can only communicate in Kiowa and has forgotten white mores. She’s white, but ultimately Indian at heart. Historically and culturally this has precedent. In general, captives who assimilated were seen as no different by other members of tribes and were adopted into families, especially amongst my own tribe: the Kiowa. Those who were retrieved are known to have had difficulty reintegrating into white society after being “Indianized” during their time away. Within this history of captives on the Plains, the tragic saga of Cynthia Ann Parker’s captivity and return is one of the most well-known examples and an inspiration for John Ford’s The Searchers, not a dissimilar film to this one. There’s brief mention of Johanna’s Kiowa family having passed and her now being orphaned twice; she wants no part of the white world and mournfully longs to return to the Kiowa. Mirroring Kidd’s impending cultural obsolescence, Johanna is similarly of a historical caste that is being phased out by both Indian and white society. She’s torn between two worlds on the brink of rapid change. There’s a humanity to Zengel’s performance that elevates Johanna beyond the captive stereotypes of Westerns past, that’s why it’s puzzling as to how the film seems reluctant to even approach Indigeneity when it is not framed through a white character.

Despite Johanna acting as a stand-in for the tribe, Kiowas only appear briefly and remotely in two of the film’s sequences. Fairly early on, Johanna spots the tribe on the horizon, defeatedly traveling under the cover of night and rainfall. She hollers for them to take her back and they either can’t or choose not to hear her pleas. Later when she and Kidd are lost in a dust storm, he faintly makes out the Kiowa as silhouettes marching through the tempest before they offer Johanna a horse in aid. In this repositioning, the two brief appearances of Kiowa people seem to express their aversion to this world and its ways. They’re ultimately benevolent when encountered and keep to themselves on the periphery. It’s a noble attempt by Greengrass to correct the ills of a narrative that’s perpetuated a legacy of subhumanizing Native Americans, but the choice ends up feeding into the very mechanism it hopes to reframe. Save for these two scenes, they’re quite literally relegated to the background of the film. Like the plight of Kidd and Johanna, the tribe and their way of life are journeying into antiquity. The Kiowa of News of the World are in the film to elicit colonial guilt and not much else. Johanna provides the vehicle into their culture and humanity, while they are reduced to tragic symbols silently fading into the shadowy horizon, obscured by distance and nature itself, or as guides who magically appear in case anyone needs their assistance. In an effort to reenvision and correct some of the more heinous tropes of misrepresenting Indigenous peoples, News of the World completes the intended function of the captivity narrative by dissolving them both within and behind a white character.

As a whole, Greengrass’ film is an ambitious but ultimately misguided effort that flattens itself under its own earnestness. Like Johanna, it finds itself torn between a number of competing desires. The result is an ultimately unsatisfactory, middling feel. It’s a film that wants to have its cake and eat it too. It attempts to reconsider the captivity narrative, one of the more openly racist subgenres of the Western, and to redeem it for the 21st century’s understanding of the effects of colonial genocide. But it’s a form that can’t be exorcised from its roots.

The white supremacist fantasy to civilize the West is exactly the idea that shapes the captivity narrative itself. The form’s very mechanism demands to be centered on a non-Indigenous view toward or against Indigeneity. Indigenous peoples are merely devices in service to that experience, no matter how close or far they are to it. In the captivity narrative, their existence is legitimized only through a white gaze’s understanding and never fully actualized until an outsider channels their humanity.

News of the World aims to reconsider the captivity narrative in a way that both condemns its history and hopes to innovate the form itself. But what initially appears as a thoughtful fix turns out to be another loop in a Gordian knot. The captivity narrative, much like Kidd and Johanna themselves, finds itself at the end of its own trail.

Read more from the Observer:

-

Identity Is A Major Factor In Our Indigenous Affairs Reporting: Two stories this week from our Indigenous Affairs desk dive into the thorny issue of belonging. Here’s why.

-

‘Truly Texas Mexican’ Bites Off More Than It Can Chew: A new food documentary fails to recognize the complexities of Indigenous identity in Texas.

-

In ‘At the Ready,’ Latinx High Schoolers Train to Be Border Patrol Agents: A new documentary tells one story of the border through three conflicted young Texans’ job prospects, and the result is emotional, relational, and hard to categorize.