“I talked a lot of shit to Spenser and Matt,” Aabria Iyengar laughs when I ask the latest Game Master of Critical Role’s Candela Obscura if there was any friendly competition between her Circle of Tide and Bone and the preceding circles, GM’ed by Matthew Mercer and Spenser Starke. “I’m just a little troll with my friends.”

It’s hard not to get excited too in talking to Aabria. Her passion is infectious, and her insight into what is being asked of her in bringing to life the third instalment of Candela Obscura - which uses an original game system now on shelves alongside the best tabletop RPGs - is keen.

“[Matt] was the perfect person to kick it off,” she goes on, “and Spenser, as part of the powerhouse that built this whole system, obviously has that very fun advantage in being comfortable and flexible inside it because he knows exactly the way the game should feel. [...] Rule of three in comedy says you establish something and then you start to mess with it at the edges, so it’s very nice coming in third, and going like: ‘You guys have set a very strong precedent, and my job is to come here and shake ever pillar that you’ve established.’”

The veil between comedy and horror is really thin

Aabria Iyengar

I put the same question, of inter-circle competition, to Liam O’Brien, one of Aabria’s players in Tide and Bone.

"Maybe if I get into this chair I’ll try and out-horror my friends," he says, joining the call from the GM’s seat at the famous Critical Role table. "For now I just love getting with a new group of people, and obviously I care deeply and love and I’m proud of everything I’ve done on our main show on the channel, but I like new groups and I like new worlds and this was just a great chance to play with people that I’ve played with before in a new way, like Aabria and Sam, and play with friends who I’ve never played this way with before."

I ask if he’d like to GM for Candela Obscura then. "I’d love to," he says. "I love horror. I love breaking hearts. So, yes, eventually."

The thrill of the rollercoaster

There is a palpable excitement in both of them, especially for the spookier stuff Candela Obscura offers. It’s also clear though that they wanted a unique take on this genre of roleplaying games evidenced by the inspirations they drew from when preparing for Tide and Bone, from both sides of the screen; The Night Circus, Penny Dreadfuls, and turn of the century exploration for Aabria. And for Liam: “If I think about what I bought to tinker with, it might have the most in common with Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, perhaps.”

The Road is a post-apocalyptic story, corruptive, and Aabria drew some parallels to those themes too, and other, more unexpected ones.

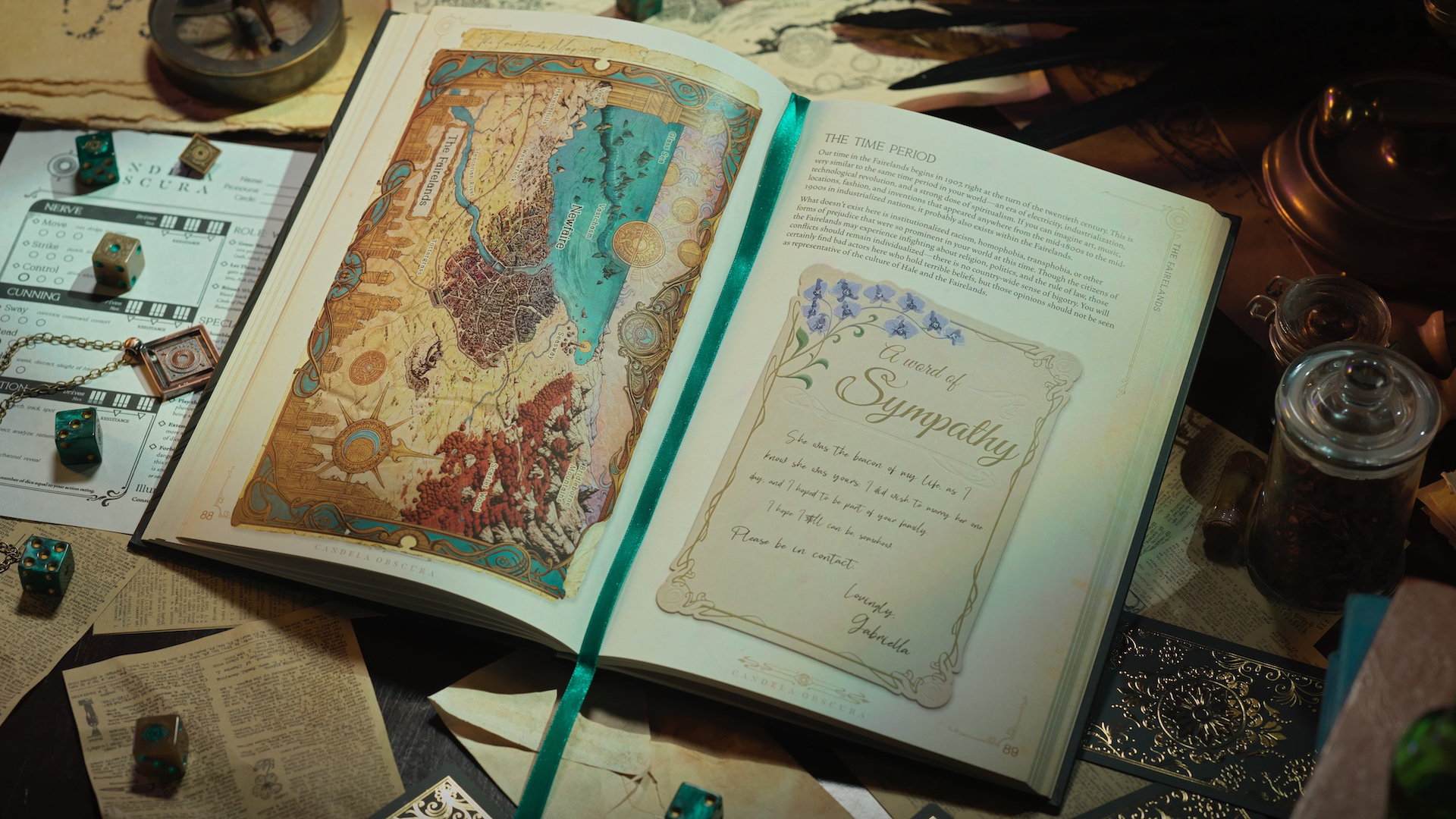

“In this world [Candela Obscura’s the Fairelands],” she says, “there is a sense of dread accumulating, it builds up, like poison in a system. The people that come to Candela, that become investigators and lightkeepers, have a little more, like, stank on them. So I think as we were kind of trying to figure out how to ratchet up the tension in the world through the lens of what these PCs look like and are capable of and the things they can do, it starts to lean a little closer to superhero films than I think most people are expecting.”

We all just want each other to have fun and feel safe and get wrecked

Liam O’Brien

Horror, as a genre, shares many roots with comedy, which Aabria touched on with her efforts to subvert the latter’s rule of three. This awareness was an asset for Tide and Bone.

“The veil between comedy and horror is really thin and small,” she explains, “because you're aiming for a big emotional payoff, and whether that's a big laugh or a big scream, it is the same thing. You're setting expectations, and you're subverting them with either time or intensity. You're playing with the same levers, you're just aiming for slightly different results.”

But despite being able to use certain frameworks in play, horror can be a difficult genre to bring successfully to your table, doubly so for horror-mysteries. Candela Obscura is certainly not the first game to occupy that space, but even more established systems can fall flat without an appropriate setting of expectations between GM and players. Aabria and Liam both credit a lot of what worked for them to their session zero.

“The session zero was wonderful,” Liam says. “I really remember that day, and it was a day, very fondly of us just sort of sitting around the table and pulling out our sad stories or, or fascinating stories, and seeing how they meshed and then changing them based on what we're hearing around the table. [...] There are for sure aspects of my own life and things that I want that are mirrored, funhouse mirrored, through my character. He’s a bit older too, and I sympathise with how tired he is.”

“Part of an important thing to protect yourself from incurring your own bleed on addressing your own feelings and fears is playing the abstraction game,” states Aabria, wisely, especially given how poor-faith GMs at the helm of horror games might wish to use the players’ fears against them, rather than the characters’. “There’re ways to alight on those fears and hit the vibe and tie yourself in, I think it’s just a matter of figuring out how to dig in, and figure out why you’re afraid of the things you’re afraid of. That becomes a fun way to play, without, you know, traumatising yourself.”

“When we talk about safety tools, they’re all ways to mechanise open communication,” she continues. “I think it's just a lot of conversation about: ‘What do you want to scare you and what do you want to avoid?’ There’s no joy in genuinely traumatising people at the table.”

“It’s horror,” Liam agrees, “and anyone who is there is signing up for the thrill of the rollercoaster, but thankfully with the excellent session zeroes that we do, it is making sure ahead of time: so you want to be scared, you want to be thrilled, but what are the things you don’t want to go near? We all just want each other to have fun and feel safe and get wrecked.”

'What if...?'

Along with player and GM safety, another aspect of horror gaming that can be hard for groups to maintain is that atmosphere of horror. Critical Role are afforded immersive sets and elaborate costumes that many of us at our kitchen tables simply aren’t, but both Liam and Aabria had great advice on how to establish and preserve the tone without all the extras.

“If everyone has that same level of buy in,” Liam offers, “[the tone] will percolate. There should be laughter and jokes at every gaming table, because what are we doing if we’re not enjoying ourselves, but if you’re aiming for horror, that tense mood, humor will come. Laughter and comedy is an excellent pressure valve in a horror story, because [...] if you can build, build, build, then laugh it off for a second, and then continue, you can climb higher.”

“If your story is dark and isolating, live in that,” Aabria adds, “but allow your players to react naturally through the full spectrum of human emotion, and I think you’ll be able to stay there.”

Horror, when it’s done well, is incredibly personal

Aabria Iyengar

“My little cheat is to ask for a player to contribute during the establishing shot phase,” she suggests. “Ask them how they feel about it, because if I can get [them] to feel about this, everything else will fall in line. I can explain the shape and decor of this room a thousand times, I don’t care about that: if you’re emotionally bought in all the other work is lighter and easier and effortless.”

From Liam’s perspective, the Candela Obscura ruleset facilitated narrative buy-in, and he highlighted the Marks and Scars as examples of enabling creative choices in expressing the personal toll of horror on a character. “It’s just a more mature version of ‘don't touch the hot lava’,” he says. “We’re adults around a table and, since we have cameras rolling, we try to keep the pace of things moving, but if you’re playing at home, there’s no problem with slowing down for a second and thinking: ‘What would that do to me and how would I react to it?’ It’s just a ‘What if?’”

“Horror, when it’s done well, is incredibly personal,” Aabria agrees. “It’s taking those quiet moments, and making it feel personal. [...] It is a game of ‘What if?’ in both directions, and you’re going to tell me, and the rest of the table, how that feels, what that looks like, how you’re character is moving through all of that, and we will feel the horror of this through the lens of the whites of your eyes as you come to terms with this horrifying thing that’s happening. I think you have to spend time and spend those beats and let it be personal and singular and quiet and isolated. I think that’s where the good horror comes from.”

For more from the CR crew, see our interview with Critical Role on breaking their world for art.