Over the past few weeks, wildfires have ravaged large swathes of Canada. The fires have burned millions of hectares of land, displaced tens of thousands of people and disrupted the lives of millions.

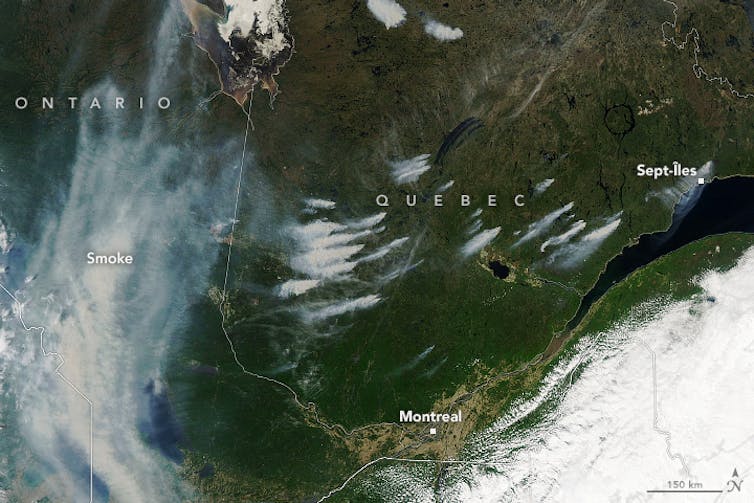

Smoke from fires in the Canadian province of Quebec blew down into the US, turning the New York skyline orange. This episode of unprecedented air pollution has drawn global attention to the fires.

But Canada has had over 2,000 wildfires already this year. More than 400 are currently tearing through many parts of British Columbia and Alberta in the country’s west, as well as Nova Scotia, Quebec and parts of Ontario in the east. Around one-third of these fires are burning in the eastern part of the country, a region that is not used to dealing with large fires.

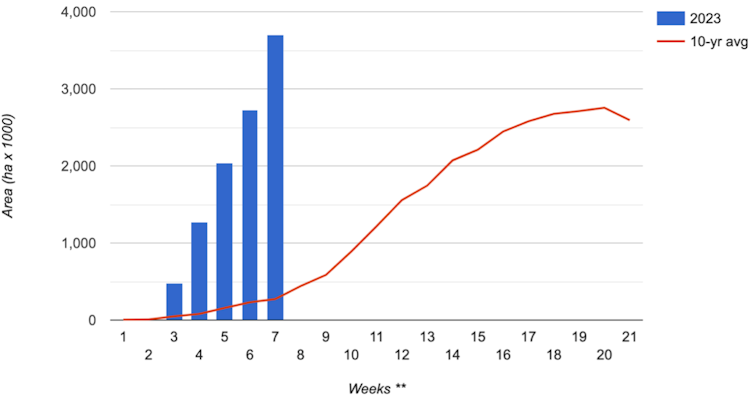

The total area burned is also striking. An area larger than the Netherlands has already burned so far this year (more than 5 million hectares), prompting Canadian officials to declare that this summer’s wildfire season is set to become the worst on record.

Experts caution that climate change and human activities will likely make wildfire seasons like this normal in the future.

Unusual timing, size, and location

In western Canada, wildfires are a natural and common part of the forest ecosystem. They remove debris and undergrowth from the forest floor, open up the forest canopy to sunlight, kill insects and diseases that harm trees and add valuable nutrients to the ground. Tree species including lodgepole and jack pines grow rapidly after a fire.

But this year’s fire season is unique because it is not isolated to a particular province. Eastern provinces like Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and Quebec – which typically have wetter and cooler climates than in Canada’s west – are seeing many more fires now than in previous years. In Quebec alone, over 400 wildfires have been reported so far this year – twice the historical average.

The size and timing of the fires has also surpassed all previous records. The area of land burned by wildfires in the past seven weeks has already reached the ten-year average for the whole season (spanning from April to October). This amount of burning is usually only reached much later in the year.

What’s causing the fires?

A particularly warm and dry spring across much of Canada has set the scene for the current wildfire situation. Many of the country’s provinces are deep in drought. In May this year, parts of Nova Scotia reported less than 50% of their average monthly precipitation.

May was also one of Canada’s hottest on record. Heatwaves pushed temperatures well above normal for this time of the year in British Columbia and in Nova Scotia. In Squamish (a town north of Vancouver), a temperature of 32.4℃ on May 13 surpassed the town’s previous record of 29.6℃ that was set in May 2018.

Heatwaves like this were seen in Siberia in 2020, where fires burned around 62,000 square miles. At the time, Siberia’s fires were larger than all the fires raging around the world combined.

Warm and dry conditions reduce moisture levels. This dries out vegetation such as trees, grass and peat (which act as a fuel for the fires), creating the perfect conditions for fires to ignite and burn more easily.

The role of climate change

There is little doubt that climate change has played an important role in the blazes across Canada. Extreme heat is made much more likely by climate change and since the mid-20th century, temperatures in Canada have been increasing faster than in many other parts of the world.

Between 1948 and 2022, the average annual temperature in Canada increased by 1.9℃. That is roughly twice the increase observed for Earth as a whole.

As the country warms, the chance of prolonged droughts and stronger heatwaves will increase. This will create even better conditions for wildfires to ignite and spread, potentially leading to longer and more intense wildfire seasons in the future.

Lightning also occurs more frequently when it is hotter. Research estimates that for every degree rise in global average air temperature, the number of lightning strikes will increase by around 12%. Lightning is a common ignition source for wildfires in many parts of Canada.

However, these more intense fires are not entirely the fault of climate change. The way humans now use forests also plays a role.

Regular controlled burns have been used by indigenous groups in Canada for thousands of years. It has proved an effective way of managing forests and reducing the accumulation of debris and undergrowth in the forest understory.

But over the past century, fire suppression has been the norm in many parts of Canada. The exclusion of fire in certain areas has disrupted the natural fire cycle. Additionally, commercial planting of tree species that are less tolerant for fire such as balsam fir and white spruce has further contributed to the increased risk of fires.

Certain provinces, including British Columbia, are now beginning to embrace traditional practices of controlled burns as a means of forest management. But challenges remain. The exclusion of fire for so long, coupled with increasingly extreme heat, has led to the emergence of extreme wildfire seasons like the one we are seeing in Canada today.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 20,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.

Iván Villaverde Canosa receives funding from the University of Leeds.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.