Canada recently took its first bold step to regulate the production and use of a large group of chemicals called per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), a family of environmentally persistent and toxic chemical compounds.

These chemicals are found in food packaging, waterproof cosmetics, non-stick pans, stain- and water-resistant fabrics and carpeting, cleaning products, paints and fire-fighting foams.

The Canadian government released a report detailing the risks of PFAS exposure and potential management options. This report, which advocates for the regulation of the thousands of PFAS as a whole, will directly influence future regulations and policies surrounding their production and use. This contrasts to previous policy initiatives that targeted PFAS individually.

As environmental health researchers, we believe that the government needs to regulate and, eventually, stop the continued release of persistent toxic PFAS into the environment and also prevent the creation of any toxic replacements.

How do PFAS affect us?

PFAS, also known as forever chemicals, are used in various consumer products and industrial processes for their water and stain-resistant properties. Recent reports even show the presence of PFAS in the fluids used during hydraulic fracturing, a process used to extract oil and gas from soil beds with low permeability.

The widespread use of these chemicals can be attributed to the strong chemical bond between the carbon and fluorine atoms that make up the backbone of PFAS. The bonds create an impermeable film, preventing grease from seeping through food packaging or water going through clothes.

However, that strong bond also leads to PFAS taking years, even decades, to break down in the environment.

Once in the environment, they accumulate in water bodies — particularly in marine species. They get more and more concentrated as they go up the food chain. For example, larger, older fish tend to contain higher concentrations of PFAS compared to smaller, younger fish.

In addition to being extremely persistent, PFAS are toxic to our bodies. They have been implicated in liver toxicity, immune system dysfunction, increased blood cholesterol, changes to thyroid hormones, cancer and birth defects.

While there are still gaps in our understanding on how PFAS cause disease, the industry has been aware of PFAS’ toxic effects on health and the environment since the 1970s — almost half a decade before the public health community. Despite this, they continued to produce PFAS and spread their application to more products in the market.

Because of their ubiquitous use, these forever chemicals are now found in every corner of the globe. A Canadian study found that at least 65 per cent of infants were exposed to PFAS in the womb.

Regulating PFAS

Some PFAS are strictly regulated.

Three of these “legacy PFAS” — perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS), perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorohexanesulfonic acid (PFHxS) — are included in the list of persistent pollutants under the Stockholm Convention, ratified by Canada.

Only a few exemptions are allowed for their production and use by the 152 member countries (not including the United States which did not ratify the convention). Canada also regulates another subset of PFAS called long-chain perfluorocarboxylic acids.

However, there are over 4,700 PFAS, and the Canadian and international regulations in place only cover a tiny fraction of the forever chemicals in the market.

Scientists have been calling for the regulation of PFAS as a chemical class, rather than wasting time examining each compound individually, as industry continues to produce and use new forever chemicals.

Populations at highest risk

As public health scientists try to catch up with the industry’s unrestrained chemical production, some populations are put at heightened risk of PFAS exposure, including firefighters, pregnant women and Arctic Indigenous populations.

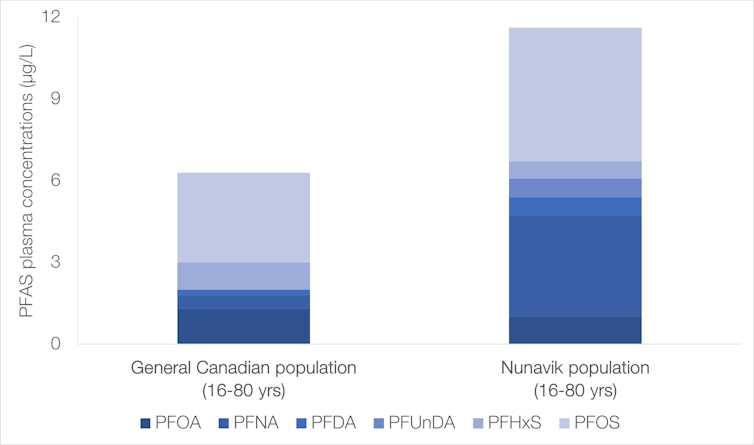

As emphasized in our report, Inuit living in Nunavik have some of the highest PFAS concentrations worldwide. Some compounds measured in their blood were up to seven times higher than the concentrations measured in the rest of the Canadian population.

This is because PFAS used in southern latitudes get transported north by atmospheric and water currents. Once in the Arctic, they enter the food web, leading to exceptionally high concentrations of PFAS in some wildlife, including species that are part of the Inuit traditional diet.

Living off the land and harvesting local species like marine and land mammals, fish and birds are integral to Inuit culture, food security and food preferences. This environmental injustice forces Inuit to think twice about consuming the nutritious foods from their own land and essential to their traditions.

Towards better regulation

The Canadian report also shines the spotlight on the need for studying PFAS mixtures. We are all exposed to various PFAS at once, be it through the use of multiple PFAS in a single product or our overall exposure to various PFAS from various sources.

Yet, we know little about the impact of being exposed to multiple PFAS at a time. Ongoing scientific studies are trying to understand the implications of mixtures on our health and how to regulate these forever chemicals accordingly.

The Canadian report is a necessary step to inform future regulations and stop the continued release of persistent PFAS in the environment. Future measures must expand the monitoring of PFAS substances in human and environmental samples in Canada, and prevent the introduction of new toxic replacements for PFAS. Substitutes for these chemicals must be deemed safe for the environment and human health prior to their release.

The Canadian report is open to the public and scientific community for comments until July 19, 2023, and we urge everyone to comment on this report to strengthen Canada’s new stance towards the adequate regulation of all PFAS — a position that has taken all too long.

Amira Aker receives funding from Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada (CIRNAC) - Northern Contaminant Program (NCP), Sentinel North (Canada First Research Excellence Fund), Fonds de recherche du Québec - Santé (FRQS), Department of Indigenous Services Canada and Genome Canada.

Mélanie Lemire receives funding from Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada (CIRNAC) - Northern Contaminant Program (NCP), Sentinel North (Canada First Research Excellence Fund), Fonds de recherche du Québec - Santé (FRQS), Department of Indigenous Services Canada and Genome Canada.

Pierre Ayotte receives funding from Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada (CIRNAC) - Northern Contaminant Program (NCP), Sentinel North (Canada First Research Excellence Fund) and ArcticNet - Networks of Centres of Excellence of Canada.

Pascale Ropars does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.