For many new cyclists, tubes have been relegated to the same category as shifter cables, rim brakes and 23 mm tires: they’re aware such things exist, but they don’t play a significant role in the riding experience.

That’s not to say everyone fits into this category: we all have a friend who swears they’ll never give up rim brakes, but the market has changed and, like it or not, tubeless tires (and electronic shifting) are now the standard.

Across nearly all disciplines of cycling tubeless tires have become firmly ensconced; the technology works well and most products are easy to both install and troubleshoot. Despite the ubiquity of tubelessness, however, tubes are not dead. There are still a few scenarios in which tubes are preferable to tubeless setups. Fortunately, tube technology hasn’t been standing still.

TPU tubes tested (listed in alphabetical order)

Models tested: NXT Gravel (35-45 mm); NXT Race (23-33 mm)

Actual weight: 65 grams; 46 grams

MSRP: $23

C02 OK: Yes

Rim/Disc: Both

Country of manufacture: Italy

Performance notes:

- Tubes are translucent with a light green coloring and black valve stem

- Robust feeling valve and well-sized reinforced area

- Valve cores are not removable

- Ride quality not as good as lightest tubes

- Design and construction very similar to Schwalbe Aerothan tubes

- Less expensive than many competitors

Models tested: Cinturato SmarTube (35-45 mm); PZero SmarTube (23-32 mm)

Actual weight: 110 grams; 36 grams

MSRP: $40

C02 OK: Yes

Rim/Disc: Both

Country of manufacture: Austria

Performance notes:

- Bright yellow tube material is easy to use/see

- Valve feels brittle

- Thicker gravel tube feels noticeably more robust, though weight is correspondingly higher

- Ride quality not on par with thinnest designs

- Heavy duty gravel tube should make for a good spare

- Design and construction nearly identical to Tubolito tubes

- Valve cores are not removable, though this is slated to change later this year

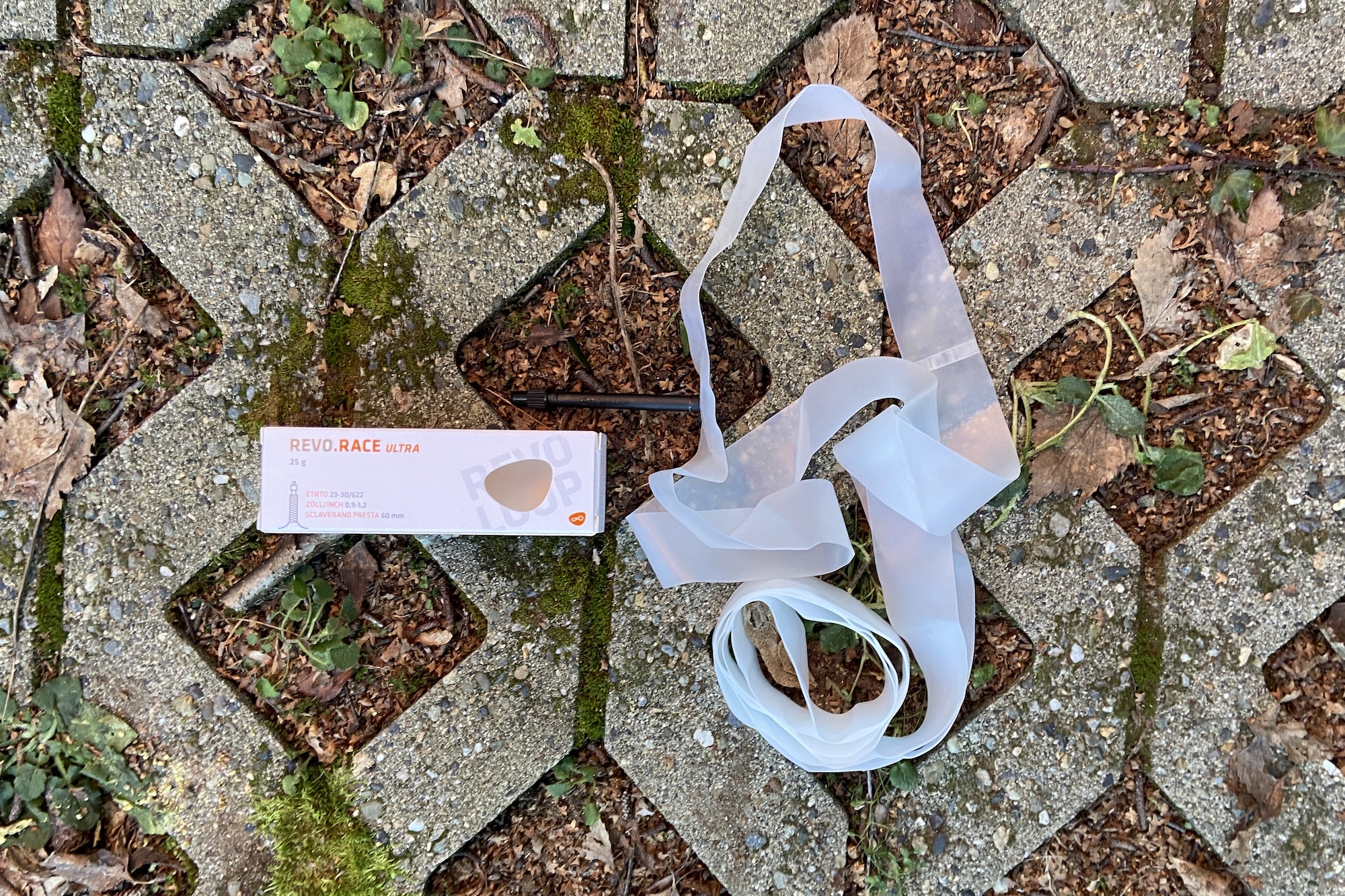

Models tested: Revo.cc ultra (32-40 mm); Revo.race ultra (23-30 mm)

Actual weights: 31 grams; 26 grams

MSRP: $37

C02 OK: Yes

Rim/Disc: Disc only

Country of manufacture: Germany

Performance notes:

- Translucent material is very supple and installs easily. One tube discolored over time for no clear reason

- Ride quality is very good

- Thermoplastic valve feels a little more robust than some others

- Reinforced area around valve stem offers some protection at a known failure point, though this area could be larger

- I punctured a Revo.cc ultra (gravel size) tube by overinflating it while trying to get a tubeless tire bead to fully seat; it held pressure up to 120 PSI

- Design and construction is very similar to Vittoria tubes w/ removable valve core

Models tested: Allround (35-45 mm); Race (23-28 mm)

Actual weight: 62 grams; 44 grams

MSRP: $32

C02 OK: Yes

Rim/Disc: Both

Country of manufacture: Germany

Performance notes:

- Texture of material helped make install easy

- Reinforced area around valve stem is large and well-shaped

- Valve core is removable

- A little bit heavier tube meant ride quality was not as good as thinner competitors

- Translucent tube color with black valves, relatively robust

- Design and construction is very similar to Barbieri tubes

Models tested: CX/Gravel (32-50 mm); S-Road (18-32 mm)

Actual weight: 63 grams; 25 grams

MSRP: $38

C02 OK: Yes

Rim/Disc: Both

Country of manufacture: Austria

Performance notes:

- Tube material is shiny and slippery, very different to softer feel of some others

- CX/Gravel tube is significantly thicker than S-Road tube

- Circular reinforcement around valve stem is well-executed

- Ride quality of road tube is very good

- Tubolito also makes tubes with a built in NFC chip that allows you to measure tire pressure via a smartphone app

- Valve cores are glued in and not removable

- I broke a Tubolito valve stem after a tubeless failure on a ride, and also cracked another one adjusting the valve core

Models tested: Ultra Light Speed (25-30 mm)

Actual weight: 30 grams

MSRP: $30

C02 OK: No (Also, no compressor use)

Rim/Disc: Disc only

Country of manufacture: Germany

Performance notes:

- Only a single size currently available

- Repair patches included with each tube

- Ride quality is excellent

- Tubes are translucent with a red valve stem

- Design and construction extremely similar to to Revoloop tubes

- Like Revoloop, valve is a little more robust and features is a small reinforced section around valve stem

- Notable that they’re recommended for disc only, though I did test them with rim brakes without issue

The 'Big Three' inner tube materials

- Butyl: This is the most common type. These are standard black synthetic rubber tubes that are easy to patch and inexpensive to manufacture and purchase. Price: $5-15

- Latex: Technically made of natural rubber, these are lighter and more flexible (and thus have less rolling resistance) than butyl tubes, but do not retain air as well. They are also more expensive and harder to repair. This is the type of tube found inside tubular tires. Price: $15-25

- TPU: Short for thermoplastic polyurethane (a type of plastic), this is the newest tube type. They can be made extremely lightweight and compact, or thick and durable. They can be recycled at the end of their lives and have less rolling resistance compared to butyl tubes. They are, however, more expensive and can be hard to repair. Price: $20-40

Why use tubes of any kind?

One of the great things about bicycles is that they last a long time. I regularly see bikes being ridden that are 20 or 30 years old, and occasionally much more than that. Most of these bikes still use tubes, because that’s what they were designed for, and not everyone needs or wants to switch.

Perhaps the most appealing attribute of tubes is the fact that they’re straightforward, with zero mess. There’s no need to top up sealant or clean out dried gunk. For people who don’t ride very often, being able to simply pump up the tires and go is the easiest option.

Tubes are also necessary when tubeless tires fail. Sometimes a puncture can’t be sealed by a plug or sealant alone, and installing a tube allows you to get home to make more involved repairs.

Another potential benefit to riding with tubes is reduced weight. Tires that are designed for tubes and clincher rims can both be made lighter than tubeless setups, which need to be more robust to prevent air from escaping. This also impacts ride quality—less material in the tire allows for a more supple (and faster, with correspondingly less rolling resistance) ride.

Some World Tour teams, such as Soudal Quick-Step, have been vocal about their use of clinchers with latex tubes for certain races over the last few seasons, when weight and ride quality are paramount. These teams, and presumably their riders, think that clinchers with tubes provide the best performance on the road. Occasionally teams still ride on tubulars, but most teams now run tubeless tires with or without inserts, depending on the parcours.

What’s special about TPU tubes?

As a newer technology, some aspects of TPU tubes are still being sussed out. TPU tubes can be made both very thin or very thick depending on the application. They are also available in a wide variety of sizes, which is not the case for latex tubes. There are a number of scenarios in which they excel, and in testing a variety of different ones I’ve learned more about how they can best be utilized.

One of the primary benefits of TPU tubes is that they can be made unbelievably light. The lightest tubes tested below weigh 25-26 grams. A very light weight butyl tube, say Continental’s Race Light, weighs 65 grams but most butyl tubes weigh closer to 80-90 grams. This weight difference, multiplied by two, makes a difference.

For the same reasons they’re light, TPU tubes are incredibly compact when rolled up. A brand new road tube can be a third the size of a comparable butyl tube. This makes them desirable as spares—they take up very little room in a saddle bag or flat kit. For bikepacking trips and similar adventures space is often more important than weight, and thus TPU tubes have become popular as it’s possible to bring several of them in place of a single butyl spare.

Rolling resistance is a tricky thing to measure, and can be subjective, but in general terms the less material present in a tire and tube module, the more it’s able to flex and give with the road surface. Thin, high-end tires combined with thin, high-end tubes provide a ride quality that “floats” over road imperfections more readily than a thicker, more puncture resistant setup. And, usually, ride quality translates to speed.

Another selling point touted by manufacturers is increased puncture resistance. I didn’t have any on-the-road punctures in the course of testing, but that may not have anything to do with the tubes themselves. Certainly the thicker tubes I tested seem like they would be harder to puncture, but that’s the extent of what I was able to determine. I did, however, experience multiple valve failures.

The laundry list of TPU shortcomings

One significant drawback of TPU tubes is the cost: they’re expensive. When a butyl tube can be purchased for $5, paying $40 for something that functions almost identically can be hard to stomach. For most people, TPU tubes are probably unnecessary, however, if weight is important to the point that you’re willing to spend hundreds of dollars chasing grams, the cost of two TPU tubes is quite reasonable.

TPU tubes are also hard to repair. When possible at all, patches need to be applied in a very clean environment for the adhesive to bond and need time to cure before they’re ready to use. In the course of my testing I found mixed success with patching punctures. Assuming the hole is small, it’s possible, but it isn’t as easy as patching a butyl tube.

They’re also temperature sensitive. Not all TPU tubes are compatible with CO2 inflators due to the extreme cold caused by the thermodynamic shift as the CO2 changes from liquid to gas. And, on the other end of the spectrum, some TPU tubes are not sanctioned for use with rim brakes due to excessive heat build up from braking friction.

The biggest issue with TPU tubes is the fragility of the valves. This is a key weight saving measure—a plastic valve is lighter than a metal one, but it’s also the likeliest failure point. Pumps put pressure on valves stems during the inflation process, and for some plastic valves this is too much. It’s a lousy feeling to be out in the woods somewhere trying to fix a flat and snap the valve off your only spare tube. I had this happen to me more than once, snapping one valve stem off completely and cracking others. Additionally, plastic valves are smooth, so a pump that threads onto the valve stem won’t work to inflate the tube, which is another scenario you don’t want to experience while out of cell-phone range.

Summary

So where does that leave us? There are clearly a variety of options on the market in a range of weights and widths. I think it’s fantastic that there are so many sizes available—this is something that latex tubes cannot match. As for the designs, there seem to be two schools of thought—one is producing different tube sizes out of the same material, while the other opts for thicker, more durable TPU material in larger tube diameters. The valves remain the same in both scenarios.

For riders who have happily accepted tubeless into their lives as their personal saviour, TPU tubes may not be very compelling. For the unconverted, however, the market’s TPU offerings are worth exploring, with a few caveats. Here are a few scenarios in which I’ve found them to be useful.

The thinnest TPU tubes are indistinguishable from their latex counterparts in terms of ride quality. I have ridden latex tubes extensively on my primary all-road bike and would consider myself a fan: typically I use them with very supple 35 mm tires in the summer when dry conditions and clearer roads make punctures very rare. I like the feeling of thin tires, which don’t work as well with sealant as the sidewalls tend to weep. I only use this setup when it’s dry however—in the winter I switch to slightly heartier tires set up tubeless. For riders who run similar tubed setups, I think TPU tubes are a great alternative to latex. They don’t lose air so fast, and should be more puncture resistant.

I also liked using TPU tubes on my road bike, where I can really appreciate the weight reduction. Making the switch feels like slapping on a very expensive set of climbing wheels. On a lightweight bike the weight difference is more noticeable than on an all-road or gravel bike. Since I only ride this bike rarely, it doesn't make sense to bother with sealant, and as my last remaining rim brake bike, it only gets ridden on dry days or the trainer, so punctures also aren’t a problem.

I can also endorse the use of TPU tubes for a hillclimb build, or a specific event where weight is paramount, like the famous Mt Washington Auto Road Hillclimb or recently started Mt Baker Hill Climb. Here, TPU tubes are a sensible, cost-effective upgrade.

For these scenarios, the Revoloop and Vittoria tubes were my favorites. I would like to see the design refined with a more durable valve for peace of mind, but that is part of the weight trade-off. It’s interesting to note that Vittoria recommends against using rim brakes and compressor inflation whereas Revoloop says yes to both: I was unable to discern any differences between the products themselves, but perhaps the difference lies in the legal counsel retained by these companies.

Though I enjoyed riding them on the road, I wouldn’t use either of these tubes as a spare. The tubes themselves seem reliable, but I don’t trust the valve stems. The purpose of a spare is to get me home and it needs to be idiot-proof. TPU tubes, unfortunately, are not, so for now I’ll stick with butyl tubes, which I know will get me home 9 times out of 10.

Many of the tubes tested do have removable valve cores, but some of them are glued in. This is something to take note of in case you plan to use valve extenders or sealant in the tubes. Because the valves are plastic, even the ones designed to be removable will wear the threads out over time.

I was much less impressed by the ride quality of the thicker TPU tubes. Though they still weigh less than butyl tubes, they don’t have the same buoyant feeling of the lighter weight models. They changed the feel of the bike completely; it felt like I was riding on cheap tires—or garden hoses—instead of the high end tires I was testing. They are clearly more durable but retain the Achilles heel of the fragile valve stems. I would consider using these heartier tubes as spares where weight and space are critical, but for a true backcountry, long-distance ride without services or emergency help I would always carry a butyl tube and patches as well.

To unlock the full potential of TPU, I would like to see some improved valve stem designs. Even a thicker TPU tube with a reinforced valve would be much lighter and more compact than a butyl tube and I think they would shine as truly reliable, durable backups. For the time being, however, I’ll stick to lighter models or latex when I want to prioritize ride quality above all else.