The story so far: The world’s quest to decarbonise itself is guided, among other things, by the U.N. Sustainable Development Goal 7: “to ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all”. Since the world still depends on fossil fuels for 82% of its energy supply, decarbonising the power sector is critical; the share of electricity in final energy consumption will also increase by 80-150% by 2050. The recent uptick in coal consumption in Europe, despite the increase in solar and wind power, suggests that reliable, 24/7 low-carbon electricity resources are critical to ensure the deep decarbonisation of power generation, along with grid stability and energy security. Small modular reactors – a type of nuclear reactor – can be helpful to India in this regard.

Challenges of decarbonisation

The transition from coal-fired power generation to clean energy sources poses major challenges for all countries, and there is a widespread consensus among policymakers in several countries that solar and wind energy alone will not suffice to provide reliable and affordable energy for everyone.

In decarbonised electricity systems with a significant share of renewable energy, the addition of at least one firm power-generating technology can improve grid reliability and reduce costs.

According to the International Energy Agency, the demand for critical minerals like lithium, nickel, cobalt, and rare earth elements, required for clean-energy production technologies, is likely to increase by up to 3.5x by 2030. This jump poses several global challenges, including the large capital investments to develop new mines and processing facilities. The environmental and social impacts of developing several new mines and plants in China, Indonesia, Africa, and South America within a short time span, coupled with the fact that the top three mineral-producing and -processing nations control 50-100% of the current global extraction and processing capacities, pose geopolitical and other risks.

Issues with nuclear power

Nuclear power plants (NPPs) generate 10% of the world’s electricity and help it avoid 180 billion cubic metres of natural gas demand and 1.5 billion tonnes of CO2 emissions every year. Any less nuclear power could make the world’s journey towards net-zero more challenging and more expensive. NPPs are efficient users of land and their grid integration costs are lower than those associated with variable renewable energy (VRE) sources because NPPs generate power 24x7 in all kinds of weather. Nuclear power also provides valuable co-benefits like high-skill jobs in technology, manufacturing, and operations.

This said, conventional NPPs have generally suffered from time and cost overruns. As an alternative, several countries are developing small modular reactors (SMRs) – nuclear reactors with a maximum capacity of 300 MW – to complement conventional NPPs. SMRs can be installed in decommissioned thermal power plant sites by repurposing existing infrastructure, thus sparing the host country from having to acquire more land and/or displace people beyond the existing site boundary.

Advantages of SMRs

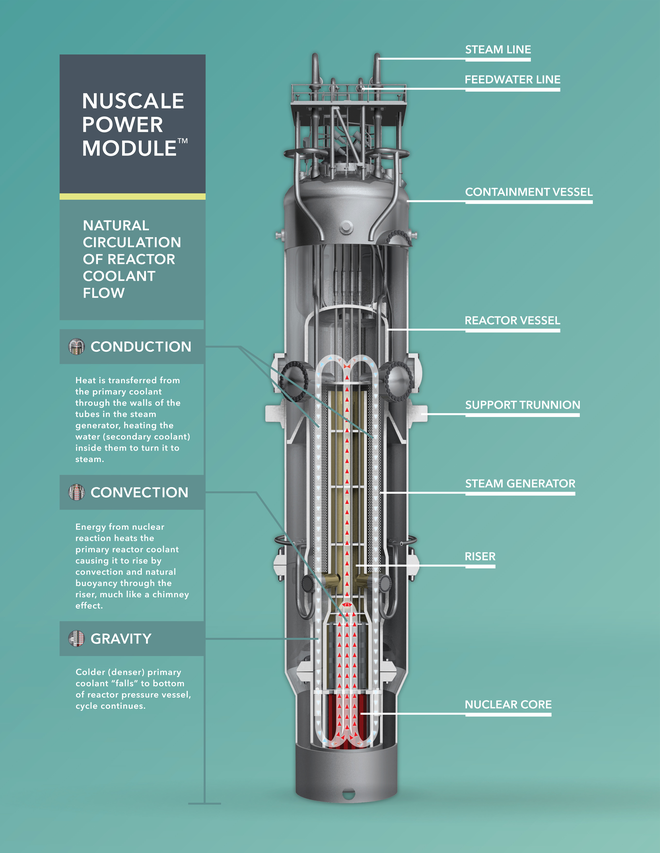

SMRs are designed with a smaller core damage frequency (the likelihood that an accident will damage the nuclear fuel) and source term (a measure of radioactive contamination) compared to conventional NPPs. They also include enhanced seismic isolation for more safety.

SMR designs are also simpler than those of conventional NPPs and include several passive safety features, resulting in a lower potential for the uncontrolled release of radioactive materials into the environment.

The amount of spent nuclear fuel stored in an SMR project will also be lower than that in a conventional NPP. Studies have found that SMRs can be safely installed and operated at several brownfield sites that may not meet the more stringent zoning requirements for conventional NPPs. The power-plant organisation can also undertake community work, as the Nuclear Power Corporation did in Kudankulam, Tamil Nadu, before the first unit was built.

SMRs are designed to operate for 40-60 years with capacity factors exceeding 90%. Since the first-of-a-kind SMR projects will be commissioned by 2030, the current capital costs for SMRs in the U.S. are about $6,000 per MW. The overnight costs will come down rapidly after 2030, especially once the many SMR projects that have already been ordered by European countries come online by 2035.

The costs for India will decline steepest when reputed companies with experience in manufacturing NPPs, such as BHEL, L&T or Godrej Industries, manufacture SMRs for India, and the world with technology transfer from abroad. This will allow zero-carbon nuclear power to expand by attracting “green” finance from the Green Climate Fund and international investors, without unduly burdening the government exchequer. This at least was the reason SMRs were included in the U.S.-India joint statement after Prime Minister Narendra Modi met U.S. President Joe Biden in June 2023.

Efficient regulation required

Accelerating the deployment of SMRs under appropriate international safeguards, by implementing a coal-to-nuclear transition at existing thermal power-plant sites, will take India closer to net-zero and improve energy security because uranium resources are not as concentrated as reserves of critical minerals. Most land-based SMR designs require low-enriched uranium, which can be supplied by all countries that possess uranium mines and facilities for such enrichment if the recipient facility is operating according to international standards.

Since SMRs are mostly manufactured in a factory and assembled on site, the potential for time and cost overruns is also lower. Further, serial manufacture of SMRs can reduce costs by simplifying plant design to facilitate more efficient regulatory approvals and experiential learning with serial manufacturing.

This said, an efficient regulatory regime comparable to that in the civil aviation sector – which has more stringent safety requirements – is important if SMRs are to play a meaningful role in decarbonising the power sector. This can be achieved if all countries that accept nuclear energy direct their respective regulators to cooperate amongst themselves and with the International Atomic Energy Agency to harmonise their regulatory requirements and expedite statutory approvals for SMRs based on standard, universal designs.

Looping in SMRs in India

India’s Central Electricity Authority (CEA) projects that the generation capacity of coal-based thermal power plants (TPPs) in India must be increased to 259,000 MW by 2032 from the current 212,000 MW, while enhancing the generation capacity of VRE sources to 486,000 MW from 130,000 MW. Integrating this power from VRE sources with the national grid will require additional energy storage – to the tune of 47,000 MW/236 GWh with batteries and 27,000 MW from hydroelectric facilities.

The CEA also projects that TPPs will provide more than half of the electricity generated in India by 2031-2032 while VRE sources and NPPs will contribute 35% and 4.4%, respectively. Since India has committed to become net-zero by 2070, the country’s nuclear power output needs a quantum jump. Since the large investments required for NPP expansion can’t come from the government alone, attracting investments from the private sector (in PPP mode) is important to decarbonise India’s energy sector.

Legal and regulatory changes

The Atomic Energy Act will need to be amended to allow the private sector to set up SMRs. To ensure safety, security, and safeguards, control of nuclear fuel and radioactive waste must continue to lie with the Government of India. The government will also have to enact a law to create an independent, empowered regulatory board with the expertise and capacity to oversee every stage of the nuclear power generation cycle, including design approval, site selection, construction, operations, certification of operators, and waste reprocessing.

The security around SMRs must remain under government control, while the Nuclear Power Corporation can operate privately-owned SMRs during the hand-holding process.

The India-US ‘123 agreement’ allows India to develop a strategic reserve of nuclear fuel to guard against supply disruptions. It also permits India to set up a facility to reprocess spent fuel from SMRs under safeguards of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). So the Indian government can negotiate with foreign suppliers to reprocess nuclear waste from all SMRs in a state-controlled facility under IAEA safeguards. The reprocessed material may also be suitable for use in other NPPs in India that use imported uranium.

Finally, the Department of Atomic Energy must improve the public perception of nuclear power in India by better disseminating comprehensive environmental and public health data of the civilian reactors, which are operating under international safeguards, in India.

The author is professor and dean, National Institute of Advanced Studies, Bengaluru.