Anxiety, a philosophical guide is a book of therapeutic philosophy. Author Samir Chopra’s aim is to take us through the history of philosophy, pointing out those thinkers along the way who have shaped its course.

In confronting anxiety then, this is not a list of prescriptions to memorise and enact, but rather, a rich vocabulary to draw upon in those silent but turbulent moments when we are in conversation with ourselves.

Review: Anxiety, a philosophical guide – Samir Chopra (Princeton University Press)

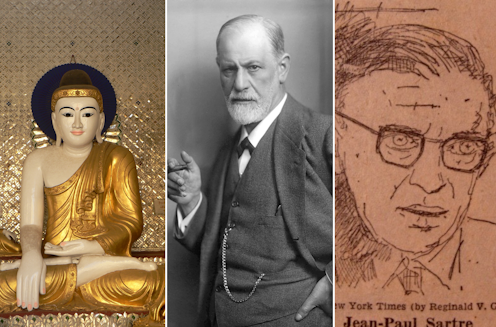

Rather than explain our anxiety away, Chopra’s aim here is to cultivate the ability to see what anxiety “points to”. In this short text, he explores four schools of thought in relation to anxiety: Buddhism, existentialism, psychoanalysis, and critical theory.

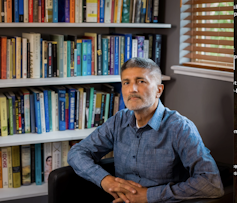

The book begins with a deeply personal and reflective account of Chopra’s own experiences with anxiety. A philosophical counsellor and professor emeritus of philosophy in New York, Chopra writes about coping with loss, his past experiences in relationships, and facing up to his search for meaning throughout his life.

Chopra writes openly about his struggle to cope with the loss of his father at a young age, and later, the loss of his mother. In seeking relief from grief, an unyielding melancholy, and his anxiety about death, he turns to philosophy. This book is very much a product of Chopra’s life experience and how he came to accept and live with his anxiety with the help of philosophy.

He begins by exploring how anxiety – and other emotions traditionally treated as aversive such as anger – can be overcome by an awareness of our “true nature”. These emotions surface in the Buddhist conception of “dukkha”, which Chopra defines as

an acute anxiety, an existential discomfort, resulting from an intellectual and emotional failure to face up to the bare facts of existence.

In order to live tranquil lives in the face of our experience of dukkha, we must embark on the Buddhist journey of “coming to see”. This is a long, difficult process of transforming how we understand the world and our place within it.

In his extrapolation of dukkha over a number of pages, one finds a variety of well-crafted phrases saying much the same thing. Essentially it is that anything we might think is good, like love or desire, is quickly overshadowed by the (re)discovery of our feelings of alienation, pain, and powerlessness in the face of the futility and absurdity of everything (although he says it better).

At this point, after so much talk of despair and alienation, it is reasonable to wonder if we are even talking about anxiety anymore.

But Chopra affirms that existential anxiety is a species of dukkha because

it is the state of being of an ignorant creature confused about its own nature, fumbling in the dark, hurting itself and others by its delusions and ignorance, by its fearful reactions to the ever-present possibility of decay, dissolution, and death in its life.

The “simultaneously disheartening and promising” solution lies within us, he suggests, as thinking beings, in our minds.

With the help of meditation and mindfulness, Chopra maintains, the Buddhist method for coping with anxiety is to make room for it in our lives. We do not just rid ourselves of anxiety then. Instead we see it as an inevitable feature of our striving to live.

Existential anxiety

For the existentialists, as the name suggests, the root of our anxiety stems from our search for existential meaning.

The existentialists defined themselves in opposition to the essentialists, who argued there was a “telos” (an end, or purpose) to everything, including our own lives. Instead, the existentialists assert, there is no meaning or purpose in life at all.

In Sartre’s famous lecture, Existentialism as a Humanism, he writes,

We are left alone, without excuse. That is what I mean when I say that man is condemned to be free. Condemned, because he did not create himself, yet is nevertheless at liberty, and from the moment that he is thrown into this world he is responsible for everything he does.

Human life is marked by a nauseating abundance of freedom, which we are condemned to do something with. Chopra writes, “we are not just creatures who are free to act; we are creatures who are aware we are free to act”.

Anxiety, then, is born out of this awareness of our freedom. For Sartre, the authentic life, the life well-lived, is one in which we courageously embrace that freedom in every choice, by thinking and choosing for ourselves.

Chopra takes us through thinkers like Nietzsche, Kierkegaard, Tillich and Heidegger to also make the case that the existentialist message is to cultivate this courage, “to realize the braveries we have already demonstrated our capacity for” and to “erect ourselves as heroes in our minds for getting up in the morning and turning our face towards the sun”.

Rather than attempt to mask our anxiety – and thus deny a fundamental feature of what it means to be – we must instead accept that in each choice, we create meaning for ourselves anew.

Psychoanalysis and critical theory

Chopra’s brief detour through the psychoanalytic tradition brings us to Sigmund Freud. The latter, he maintains, would double down on this existentialist call for courage, with the added proviso that attempting to repress anxiety is futile.

Repressed anxiety only comes to surface in parts of our lives, particularly our social lives. Freud suggests a trained and mature response to anxiety involves better understanding how it forms part of life, how it arises in our childhood, and how it surfaces for us now.

There is also a particular category of anxiety assigned to the uncertainty brought on by our ever-evolving social and political environments.

Chopra argues this anxiety points to a lingering fear of losing our economic standing, along with an agonising over our social and moral adequacy. This anxiety has not been helped, he continues, by science and technology, which “hurtle us toward climate change, mysterious pandemics, and political dysfunction”.

Chopra turns to Herbert Marcuse and Karl Marx to suggest that, contrary to the existentialists, this anxiety and alienation are not inevitable features of the human condition. Rather, they are a product of the world we have created.

Our experience of anxiety, he continues, should spur activism and political critique in the hope that we might make this world slightly more bearable:

Combating and confronting anxiety requires acceptance, activism, and contemplation, an acute blend of which might be the salutary recipe for living with it.

Overall, Chopra does a great job bringing difficult philosophical perspectives into his conversation about anxiety. However, anxiety appears to have many roles in this book, roles we might usually ascribe to other emotions or moods, like estrangement, wonder, alienation or sorrow.

By implicitly running together these many forms of experience, Chopra risks reading too much into these philosophers at times. A consequence of this is overlooking what makes these experiences unique.

Still, by sharing his own experience with anxiety, as well as connecting us to the extensive philosophical literature where anxiety is explored, Chopra and his philosophical interlocutors are offering a powerful and therapeutic insight: we are all bound together in the human condition that always has, and will continue to involve, encountering our anxious selves.

Oscar Davis does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.