Flooding and slips have highlighted the need for climate due diligence in real estate

It’s safe to say that prospective home-buyers in Auckland will be looking at maps of flood plains and potential landslide zones with greater reverence in future.

The wild weather of the past few weeks has seen homes inundated with rapidly rising waters and crushed by toppling cliffs.

Most tragically, out in the coastal village of Muriwai, one volunteer firefighter was killed while another ended up in critical condition in hospital after a landslide took out a house they were assessing for flood damage on Monday night.

READ MORE: * 10k displaced by Cyclone Gabrielle as rescues continue * 'We are entering a period of consequences'

The earth gave way en masse along Auckland’s west coast, with towns like Muriwai, Piha and Karekare all reeling with access issues and property damage following multiple land slips.

While west coast locals are still picking up the pieces of their damaged communities, scientists like University of Auckland geologist Martin Brook are wondering if we make enough information available on the dangers of the places we live.

“That information might not be on your LIM report for your property,” he said. “People get very particular and very insecure about things appearing on their LIM reports - so that's a big problem in New Zealand I think, and I don't know how to square that circle.”

It’s a problem that isn’t going away for Auckland or New Zealand in general.

“A lot of Auckland is at a risk to landslides, without a shadow of a doubt,” he said. “What kind of risk curve are you prepared to follow in your house purchase if you're looking 10, 20 years down the track.”

He said areas like the west coast of Auckland were particularly vulnerable to destructive slips, both due to the topography of the area, but also because of the sandy soils overlaying the bedrock.

"On the west side of Auckland we do have this younger sand-like material which is formed from old sand dunes, overlying more competent bedrock which is much older - several million years older - and the sand, it's weak," he said. "And when it saturates it does fail... It's not an unknown feature of these weak sands that occur on the West Coast."

And with most people’s biggest asset being their house, the impact of wilder weather could have resounding knock-on effects to the economy.

Property data specialists CoreLogic highlighted flood damage and coastal erosion as factors that will hike prices for the residential sector over the next decade.

The average annual cost of river flooding to residential buildings already tops $100 million per year, and that could increase by more than 20 percent by 2050.

That research was done in conjunction with reinsurers Munich Re Australia, whose managing director Scott Hawkins said understanding and managing exposure to climate risk is essential.

“New Zealand will see an increase in both the frequency and severity of weather events due to climate change,” he said.

“Weather-related disasters might in sum become as destructive to New Zealand as earthquakes.”

Natural hazards and the increasing threat of climate change should be easier for consumers and businesses to track once mandatory climate-related disclosure laws kick into action later this year.

The new rules are supposed to ensure that the effects of climate change are routinely considered in business, investment, lending and insurance underwriting decisions.

Needless to say, making considerations for these things is expensive.

It’s a concern for the finances of people living in hazard zones if house and contents premiums are set to rise. It’s a cost that’s already increased by 150 percent over the last decade.

Brook said that while the geotechnical surveillance industry in New Zealand is well-managed, it often comes down to a cost issue when people start asking questions about the risk profile of a property purchase.

“There are hundreds of chartered engineers and engineering geologists who can do a range of surveys on houses and properties from quite a rudimentary site walk over or desktop study to an intrusive borehole investigation, which people who are constructing houses do as a matter of course,” he said. “It’s a matter of what you're prepared to pay.”

But why aren’t those ‘matter of course’ investigations already preventing people from living in dangerous places?

New building consents consider how affected the building could be by natural hazards, including erosion, subsidence, flooding and land slippage.

The Building Act says the council can’t give consent unless adequate provision is made to protect the building or restore any damage it might do to the land.

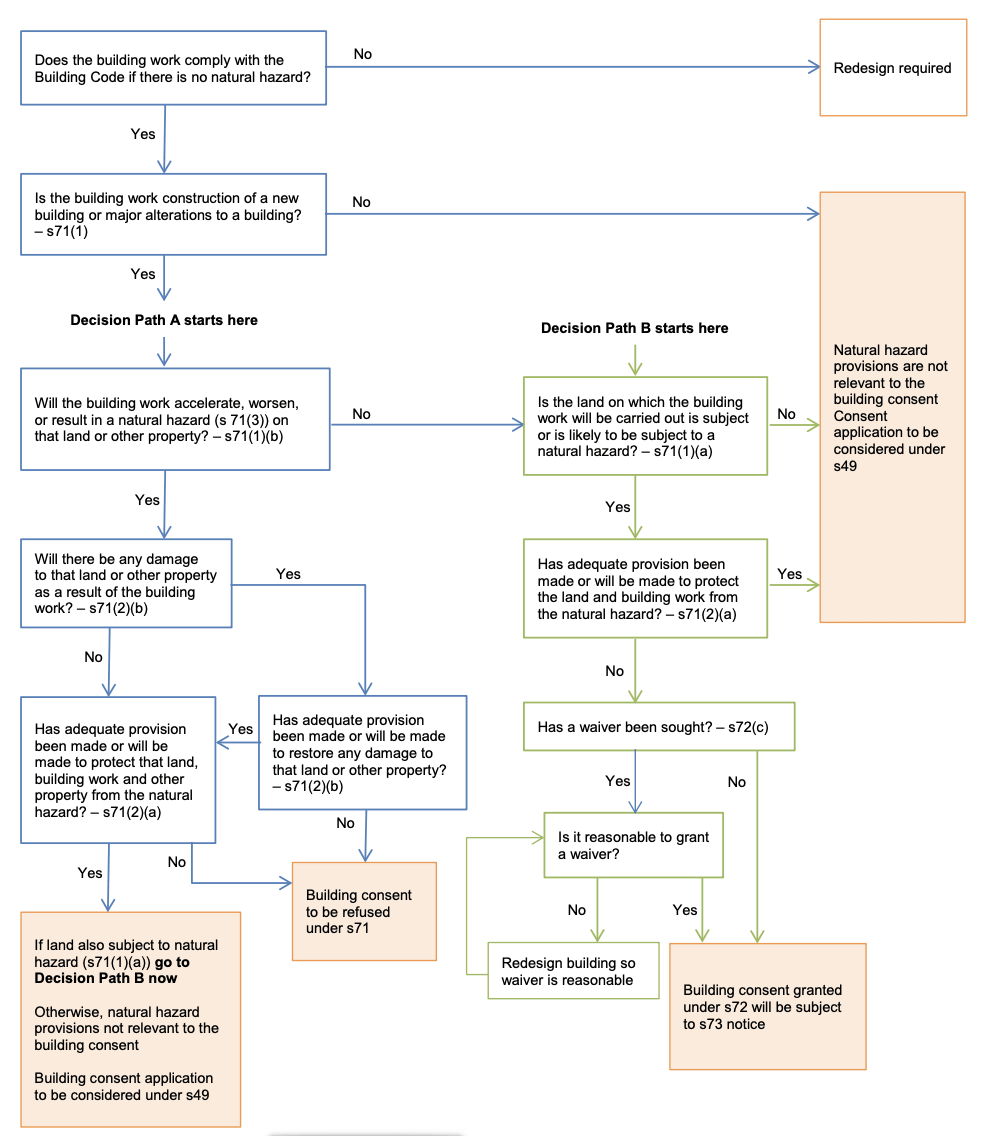

The Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment published a decision tree detailing just how territorial authorities should be going through consent processes for buildings in hazard zones:

But whether the consent is given or not ultimately comes down to the nature of that aforementioned ‘adequate provision’.

North Shore councillor Chris Darby expressed surprise last week at a meeting of Auckland Council’s civil defence and emergency management committee around how many houses had been consented in potentially hazardous zones within the region.

According to monthly housing reports from last year, 18 percent of dwellings given consent in November were in a flood zone, erosion zone or near a cliff. The following month that figure was 16 percent.

It amounts to more than 2000 homes over the past 12 months consented in hazard zones.

“I never realised that we were consenting so many buildings to be built in such places and then thousands of people to be put in those places - to live, but maybe not fully understand the place that they are living in,” he said.

It’s a sentiment Mayor Wayne Brown raised in the first few days following the anniversary weekend floods - maybe some of those houses shouldn’t have been there in the first place.

His comments received criticism for coming just as families had lost loved ones and the disaster had just happened, but it’s nevertheless a sentiment echoed by climate scientists and city planners around the world.

What once seemed permanent has taken on a newly fleeting flavour in this world in which unprecedented weather events are quickly becoming, well - precedented.