Russia’s ongoing invasion of Ukraine has brought fossil fuels and geopolitics to the forefront of public discussion. In an effort to evade economic sanctions, Russia has weaponized its energy exports.

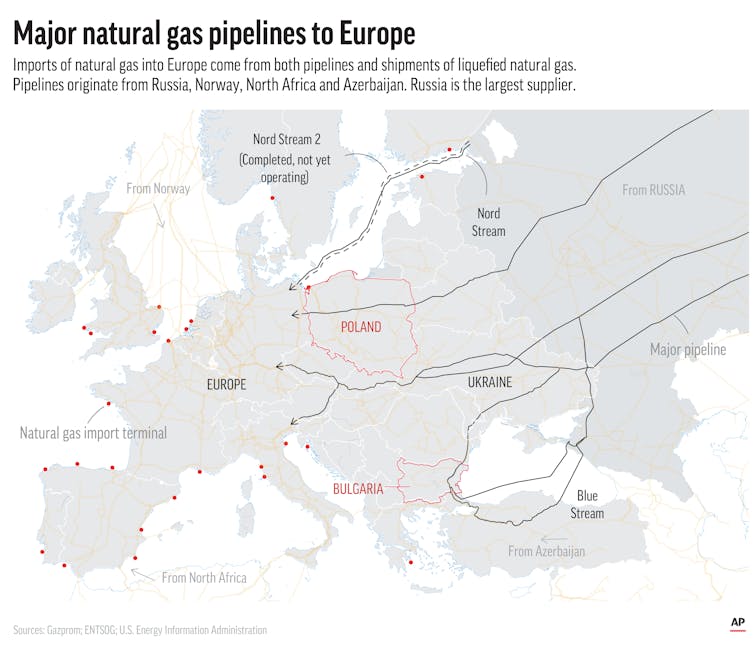

In March, President Vladimir Putin said he expects “unfriendly” countries — those that have imposed sanctions over Russia’s war in Ukraine — to pay for gas sales in rubles. In May, Russia halted gas supplies to Poland and Bulgaria after they refused to pay in rubles. The European Union buys a significant portion of its natural gas (40 per cent) and imported oil (27 per cent) from Russia. Some analysts have said a few countries, like Germany, could see a recession if gas from Russia were completely cut off.

The escalating energy crisis has reignited calls to increase the production and export of Canadian oil and gas to diversify Europe’s energy supply. Pro-bitumen think tanks such as the Canadian Energy Centre and the Macdonald-Laurier Institute have made similar arguments accusing opposition to pipelines as dooming western countries’ energy security.

In essence, these arguments repackage the ethical oil rhetoric that frames investment in bitumen as morally superior to oil from non-democratic regimes. But the significant expansion of bitumen infrastructure comes with economic uncertainties and contradicts Canada’s COP26 commitment to decarbonization. Moreover, it diverts public attention away from the inconvenient reality that Canada and Russia are petro-states that share numerous similarities in energy policy making.

Oil booms and petro-states

Political scientist Terry Lynn Karl introduced the idea of a petro-state in her 1997 book, The Paradox of Plenty: Oil Booms and Petro-States. She developed the petro-state thesis to explain the inability of oil-exporting nations such as Saudi Arabia and Nigeria to convert their petroleum revenues into more stable and self-sustaining economies.

Karl’s main insight was that a nation’s reliance on oil exports leads to economic and political problems such as weak economic growth in manufacturing sectors, vulnerability to price shocks, widespread social inequality, authoritarianism, corruption and so on.

Throughout the first decade of the 21st century, soaring oil prices substantially altered the global energy demand and supply landscape. This trend considerably bolstered the oil and gas industry in countries like Canada, Norway and Russia. In response, scholars began to debate whether the petro-state thesis should include them, given their increasing dependence on fossil fuel revenues.

For instance, scholars noted that Russia is compelled to prioritize the energy sector over other economic sectors due to the influence of natural gas in generating export revenues and in sustaining its geopolitical influence in Europe. This results in an economic structure that is vulnerable to energy market volatility. In 2020, record-low oil prices imposed a hefty cost on Russia, contributing to a dramatic currency depreciation and negative GDP growth for the whole year.

Overcome the petro-state curse

Scholars have debated the extent to which Canada can be classified as a petro-state. After all, energy products only account for 8.3 per cent of national GDP, which is notably lower than typical petro-states. Nonetheless, the Canadian economy and well-known petro-state economies exhibit comparable structural vulnerabilities.

Canada’s energy sector has struggled from declining demand, as a result of the pandemic. Alberta, Saskatchewan and Newfoundland and Labrador rely heavily on the energy sector, and have been hit especially hard.

The resurgence of “ethical oil” narratives that moralize bitumen extraction and demonize critics aim to frame resource dependence as part of Canadian identity. Put differently, the bitumen industry and its allies are pushing for “petro-nationalism,” which symbolically celebrates bitumen while obfuscating the unequal distributions of bitumen’s economic benefits and its environmental costs.

In search of a path to net-zero

Days after Russia’s Feb. 24 invasion of Ukraine, Alberta Premier Jason Kenney tweeted, “Now if Canada really wants to help defang Putin, then let’s get some pipelines built!”

However, building more pipelines to increase the Canadian economy’s reliance on fossil fuels is not the only option. Norway, whose economy is currently reliant on the oil and gas industry, is a shining example of how to overcome the petro-state curse.

As policy analyst Bruce Campbell has written, instead of the denial, delay and division that characterizes current Canadian climate policy, Norway’s path to net-zero is built on climate action, close collaboration with labour unions and NGOs and strong government leadership in collecting and redistributing energy revenues.

Read more: 5 ways Norway leads and Canada lags on climate action

If Canada is truly concerned about becoming a moral energy producer, then our public conversations need to focus on exploring immediate policy actions aimed at limiting greenhouse gas emissions from the energy sector and planning for its phaseout.

Sibo Chen receives funding from Toronto Metropolitan University and Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.