The results of Thursday’s by-elections are unquestionably bad for the Conservative Party and a prime minister whose key selling point has been that he is an election winner.

The result in Wakefield will give pause for thought to the northern Tories, elected with relatively slim majorities in 2019, who so far have largely backed Boris Johnson, believing he won them their seats and could do so again.

Polling data since partygate has consistently suggested they were at risk, but the concrete reality of a by-election defeat in a red wall area will have more of an impact than suggested by the polls.

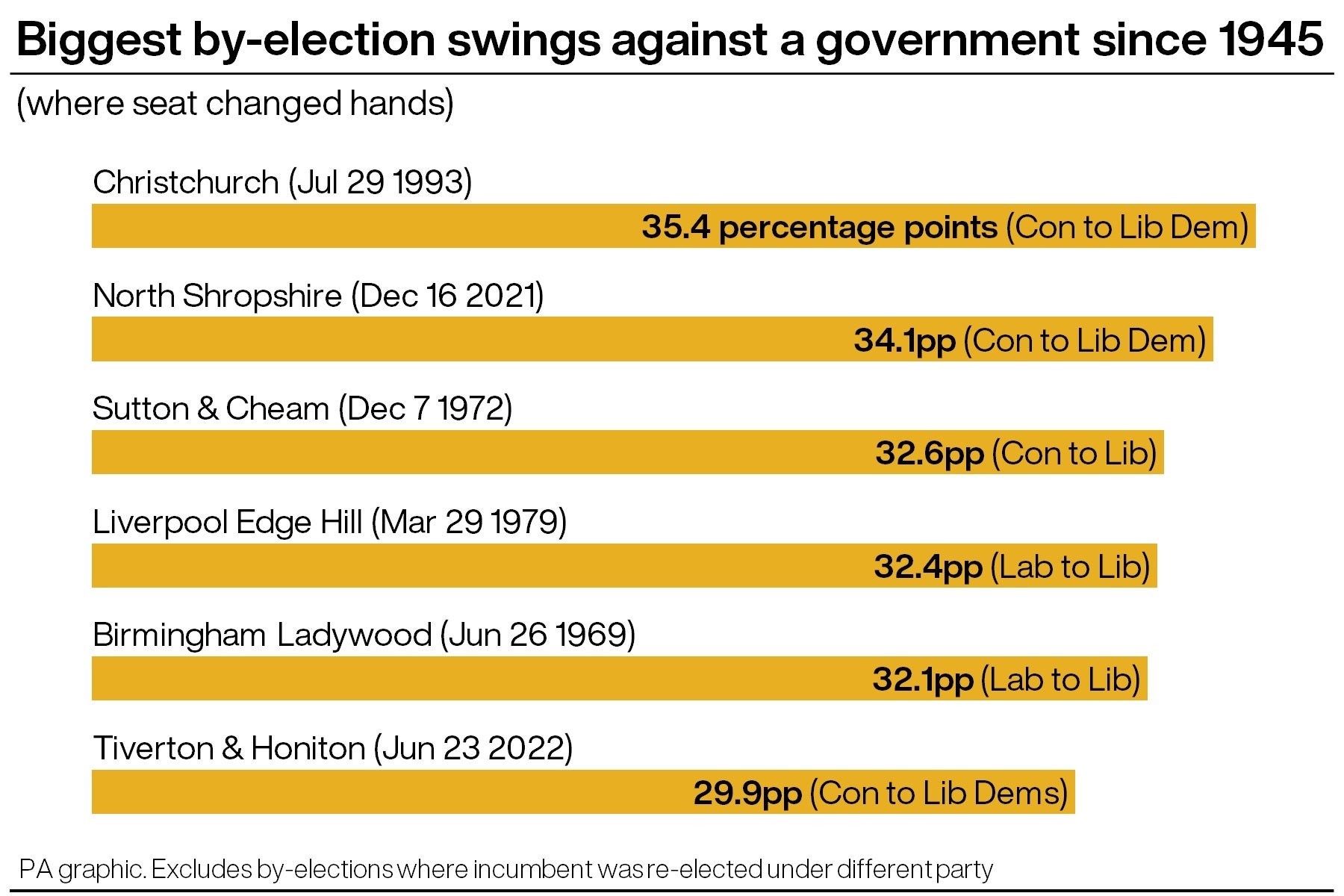

But it is the result in Tiverton and Honiton that will most concern the Tories, with the Liberal Democrats overturning a majority of 24,000.

The scale of that victory is highly unlikely to be repeated in a general election, but it will make uncomfortable reading for many Conservative MPs, who previously thought themselves safe.

There are two factors common to both these by-elections that should concern Tory strategists.

One is the scale of tactical voting, with voters seeming to prioritise defeating the Conservative candidate over voting for their preferred one.

In Wakefield, the Lib Dems lost their deposit after barely getting 500 votes, but the biggest effect was in Tiverton and Honiton.

Labour went from coming second in 2019 with 11,654 votes to third with just 1,564 as voters calculated that the Liberal Democrat was more likely to win.

It will be difficult to repeat that pattern across the country during a general election – it can be much harder to identify the favourite non-Tory candidate when attention is not focused on one seat – but even a moderate increase in tactical voting would spell bad news for the Conservatives.

The other factor is the fact that many Tories simply stayed at home. Some of this will be the impact of a by-election, when turnout is often reduced, but the number of Tory votes fell by much more than the decline in turnout.

What this suggests is that the current Conservative tactic of trying to energise the party’s supporters with ‘red meat’, such as transporting asylum seekers to Rwanda or getting tough on trade unions, is not working.

The priority for most voters remains the cost-of-living crisis. A survey of 1,000 British adults by Ipsos between Monday and Wednesday found 85% were following the crisis closely, while less than 60% were following either the strikes or the Rwanda policy.

Where this leaves Boris Johnson is uncertain. In his resignation letter, party chairman Oliver Dowden appeared to blame the Prime Minister for the defeats, saying supporters are “distressed and disappointed by recent events” and the party cannot “carry on with business as usual”.

But while Mr Dowden’s is a high-profile resignation, unless other ministers go with him it seems unlikely to persuade Mr Johnson to quit.

It is possible that two catastrophic by-election defeats and Mr Dowden’s resignation will help the backbench 1922 Committee change the rules to allow another confidence vote within a year of the previous one, but up to now there has been little appetite for such a change.

Beleaguered on several fronts, the Prime Minister is running out of options. If the 1922 Committee does not change the rules, he can cling on for another year in the hope things improve, overseeing a fractious party and facing rebellions in Parliament.

Or he can call a general election in the hope he can demonstrate the election-winning ability that brought him to the premiership in the first place.

It would be a high-stakes gamble, especially at a time when the cost of living is soaring, but it may rapidly become his only faint hope of remaining in Number 10.