In less than 550 years, all Japanese families will have the same surname, according to a new study.

The research, published by Tohoku University's Research Centre for Aged Economy and Society, argued that Japan's current surname system threatens "individual dignity" and the loss of family identity.

Current laws in Japan dictate that families should adopt one family name after marriage.

While the law excludes those who have married foreign nationals, the legislation poses a threat to female heritage as social stereotypes are pushing heterosexual couples to opt for the male family name.

The study also explored the trajectory and demographic trends of the most common surname, noting that the prevalence of the name "Sato" surged by 1.0083 times in the 12 months between 2022 and 2023.

"Sato-san" was listed as the most common name in Japan, accounting for 1.5 per cent of the total population.

Professor Hiroshi Yoshida, who is responsible for the study, predicts that all Japanese people will be called "Sato-san" by 2531 unless the civil code changes.

The researcher also warned that if the marriage surname law stays the same, half of the population will share the last name "Sato" by 2446.

"If everyone becomes Sato-san, we might have to resort to calling people by their first names or even numbers for identification. That wouldn't make for a particularly wonderful world, would it?" Professor Yoshida said.

However, if the laws were altered, allowing couples to keep their last name after marriage and choose double-barrelled surnames for their children, the name wouldn't dominate Japan until 3310.

Professor Yoshida estimated that, by 3310, if the nation's declining birth rates continue, Japan's population will consist of just 22 people.

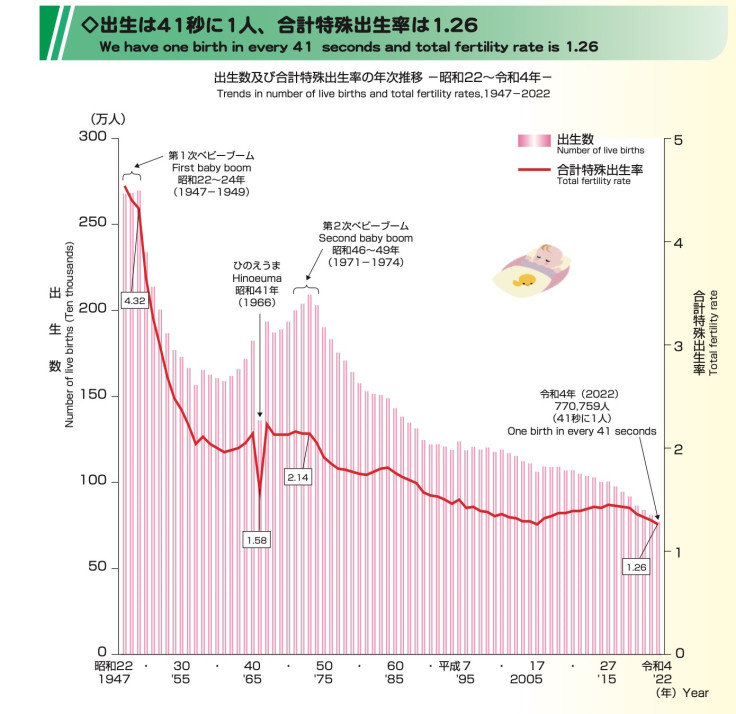

Japan's birth rate fell by more than five per cent between 2022 and 2023. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan/Vital Statistics of Japan

The researcher also said that unless a separate surname system is implemented, the diversity of Japanese surnames will be limited until the population ceases to exist.

The report also explored an alternative scenario based on a survey conducted by the Japanese Trade Union Confederation in 2022.

In the survey, which interviewed 1,000 Japanese employees aged 20 to 59, 39.9 per cent of respondents said they would choose to share a surname with their partner regardless of the option of using separate ones.

With this scenario in mind, Professor Yoshida predicted that just 7.9 per cent of the Japanese population would be named "Sato" by 2531.

In a bid to legalise the opportunity to choose one's surname in Japan, the report was commissioned and organised by the Japanese website Think Name Project and the general incorporated association Asuniwa.

According to Professor Yoshida, the groups asked for his assistance and support.

"I sympathised with their goal of putting issues related to the selective separate surname system into numbers," he said, highlighting how his research is "mechanically calculated based on an assumed scenario."

The threat to Japanese heritage comes as Japan's birth rate hit a record low in 2023.

In February this year, Japan's Health and Welfare Ministry revealed that the number of babies born in 2023 was 758,631. The shocking statistics exposed a 5.1 per cent decline compared to 2022.

Japan's Chief Cabinet Secretary Yoshimasa Hayashi said that the lacking birth rate is at a "critical state" and went on to note: "The period over the next six years or so until the 2030s, when the younger population will start declining rapidly, will be the last chance we may be able to reverse the trend."

"There is no time to waste."