Two decades after her son went missing, Soledad Ruiz was handed a small coffin containing his remains, identified using DNA and the sweater he was wearing when he disappeared.

Her face worn by grief and time, Ruiz wipes away tears as she clutches a composite sketch of her son, Apolinar, who was 25 when he left for work on a farm in San Onofre in northern Colombia in 1999, never to be seen again.

The Caribbean region of Sucre was then a hotspot for paramilitary groups, brutal far-right squads that formed to combat leftist guerrilla groups but also became involved in drug trafficking, extortion and atrocities.

Ruiz long thought her son had been killed by a paramilitary leader who was known for throwing the bodies of his victims in a caiman-infested river.

However, his remains were found buried elsewhere in San Onofre with the fragments of his old sweater, and his identity confirmed by comparing his DNA to his mother's.

"I wanted him alive. I didn't want him as he came," what was left of him placed in a tiny coffin to be buried 24 years later, Ruiz told AFP.

"But that is how it is, it was his destiny."

Across Colombia, efforts have intensified to find, exhume, and identify those who have gone missing during the country's six decades of armed conflict, since a 2016 peace agreement was signed with the Marxist guerrilla group, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC).

The Search Unit for Persons Reported Missing (UBPD), created after the peace deal, said it has found 1,256 bodies -- including that of Apolinar -- and is still looking for 104,000 more missing.

It's no easy task in a country where armed groups still wreak havoc, even as the leftist government of President Gustavo Petro tries to negotiate peace with several of them.

Hadaluz Osorio, a forensic anthropologist at Legal Medicine, which is involved in the identification of bodies, said paramilitary groups, guerillas and even state agents had tried to hinder the search.

"They murdered people and buried them clandestinely," she said.

In some cases, the perpetrators have exhumed the victims "and divided their remains into different graves to make it even harder to identify them," she said, surrounded by the bones of suspected victims in a Bogota laboratory.

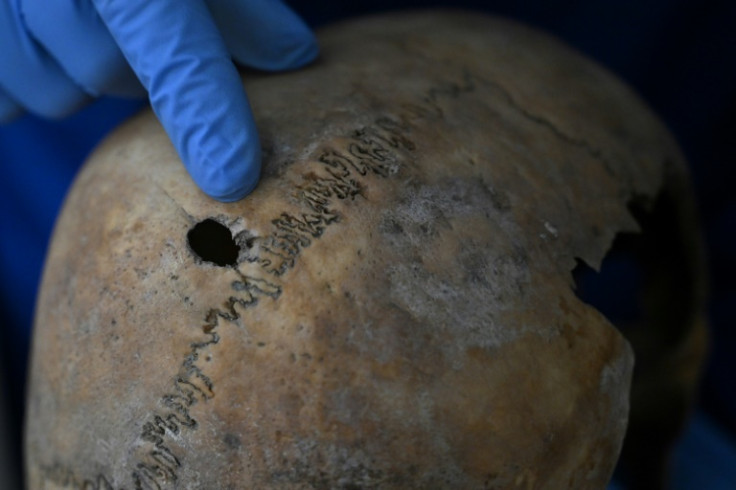

Osorio examines a skull where the neat entry and explosive exit of a bullet are clearly seen.

Another skeleton shows cut marks that could be from a machete. That victim also has signs of wear and tear on their knee -- a valuable clue to relatives whose missing loved one may have complained of knee pain.

It's about "translating what the dead are telling us," said Osorio.

Her colleague Grace Alexandra Terreros grinds bone fragments and teeth into powder to extract DNA which is compared to samples kept in the "Bank of Genetic Profiles of the Disappeared."

Created in 2010, the bank contains at least 62,000 blood samples from family members of the missing.

The Special Jurisdiction for Peace (JEP), a court set up after the 2016 peace deal, has called for the process of identifying bodies to be sped up to help families heal their wounds.

Soledad Ruiz said she is more at ease since Apolinar's remains were found, but she is still waiting for news of her younger son, Jose de los Santos, who disappeared 15 days after him.

One of her grandchildren, Jimy, also went missing in 2001.

"I want them to come back, dead or alive," she said from her rural thatched-roof home, where chickens peck in the dirt near some banana trees, and horses graze in the distance.

Jimy's mother Alba Silgado is convinced she will soon get a phone call announcing that the remains of her son and brother have been identified, "even if it's because of hair, even if it's because of a fingernail."