Thiruvananthapuram, India – A tangled gun strap almost cost Prince Sebastian his life.

It was 6pm local time on February 4. Prince and his contingent of soldiers fighting for the Russian army were advancing towards a battlefield in Luhansk in occupied Ukraine. It wasn’t what Prince – a fisherman from the southern Indian state of Kerala 5,470km (3,400 miles) away – had signed up for, but at that moment, he felt he had no option but to keep moving, a Russian soldier by his side, the frantic symphony of gunfire their unwelcome soundtrack.

Suddenly, there was chaos as they came under attack, a hail of bullets fired in their direction. A superior barked out orders, asking the soldiers to fire back. But in the split second that Prince lost because of the tangled strap, a bullet ricocheted off their Russian tank with a sickening thud and pierced his left ear, flooding his mouth with blood.

“I crumpled onto a dead Russian soldier,” Prince recalls. “I was hit, but there was no pain, it was numbness for a few seconds.”

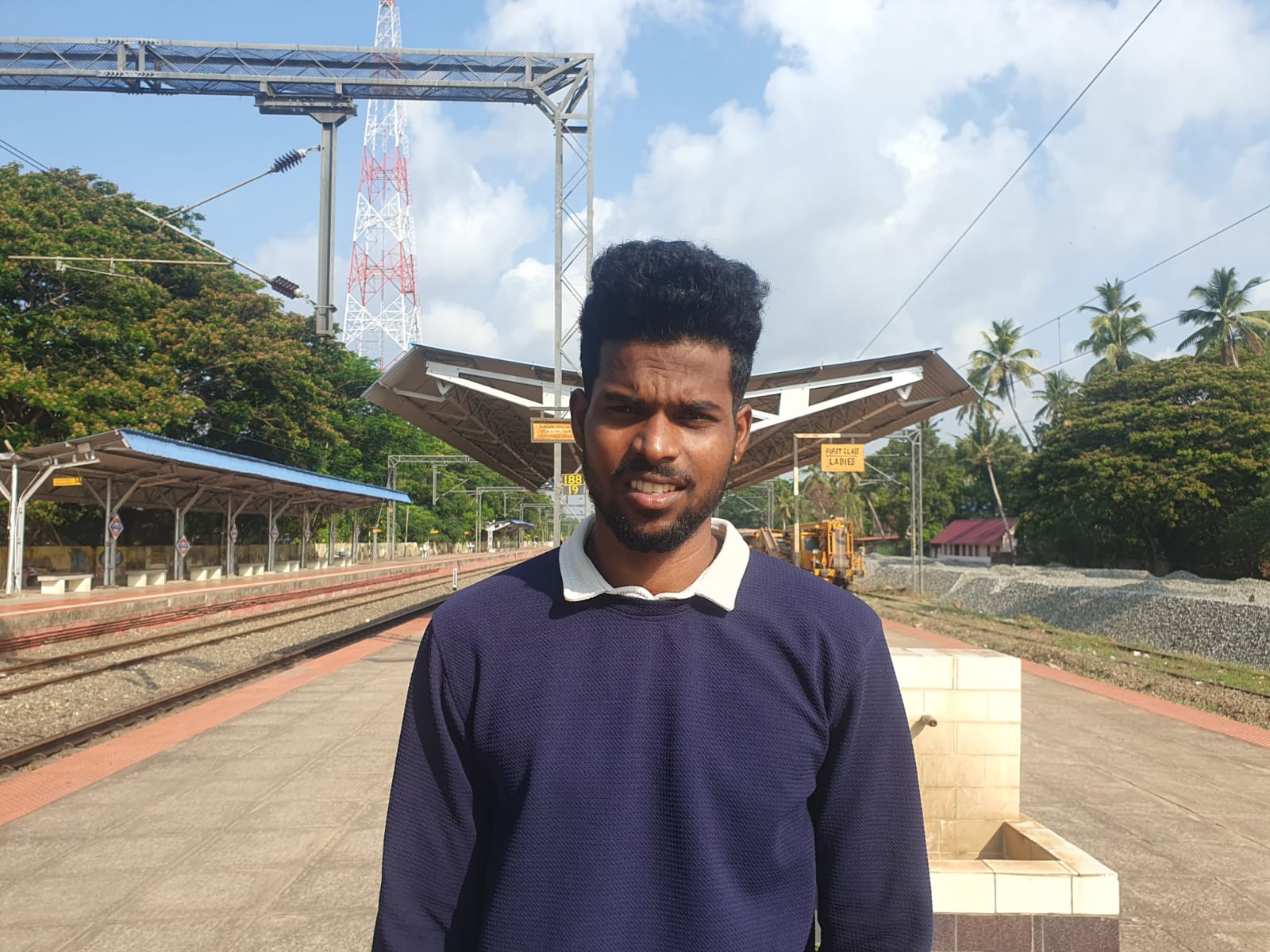

When he slowly came to his wits, Prince began a long, 3km (1.8 miles) crawl through mud and an even longer fight to escape Russia’s army. Now, two months later, he is back home in Anju Thengu, a coastal village near Kerala’s capital Thiruvananthapuram, safe from the war he had found himself trapped in.

But as the lean 24-year-old recalls the horrors that he managed to leave behind, he knows he has returned to the very life he had tried to get away from when he went to Russia: one of poverty, joblessness and an uncertain future. He’s back where he started, with a lifetime’s nightmares to boot.

Fishing for a future

It was the dream of a new start that made Prince and his fishermen cousins, Vineeth Silva and Tinu Paniadiam, all in their early 20s, decide to migrate to Russia in January.

Increasingly erratic weather patterns have reduced both the number of days fisherfolk can head out to sea and the catch they return with. The shoreline has suffered from human activity. And there are few other jobs around. Kerala has long had among India’s best education and health indices, but it also has the highest unemployment rates for young adults in the country: more than 28 percent, compared with a national average of 10 percent for people in the 15-29 age group.

“In the past, some 10 years ago, when I started to go fishing with my father and uncles, a good catch was guaranteed and the fishing season used to last for more than six months,” Prince said, four days after the returning from the Russia-Ukraine warfront. “But during the last few years, the fishing season has shrunk to three months and the catches have become very poor.”

The offer of a job as a security guard in Russia, which came through a recruiter, proved irresistible for Prince and his cousins. In freezing January, they arrived in Moscow after each paying $8,000 to the recruiter, only to be separated on landing by the recruiter’s Indian representative in Moscow.

Prince was taken away to an apartment, where he was confined for four days. He got food, but no answers to the gnawing doubts that were growing by the hour: What was going on?

“Finally, the truth emerged – we weren’t there for the advertised position; we were expected to join the Russian army as helpers,” Prince said.

The recruiter, whom the cousins had already paid in full, was no longer reachable. “We had no choice but to follow the representative’s orders,” Prince added.

A Russian official took Prince to an army camp in Rostov, the southern Russian city that is the headquarters of the Kremlin’s war in Ukraine. The officers spoke to Prince in English, but he had to sign several documents in Russian – which he couldn’t understand.

“I realised we had been cheated. But I had no other option but to obey the barking orders of the Russian commanders. I braced myself to adjust,” Prince said.

Prince, along with hundreds of Russians and a “handful” of Indians underwent training in physical fitness and first aid at the military camp. After 10 days, they were moved to another camp nearby where they were given arms training for 13 days – bodies sculpted for a life at sea being moulded to fire weapons.

They learned how to use AK-47s, rocket-propelled grenades, and M60 machine guns – far removed from what Prince thought he would be doing in Russia when he boarded the flight from India.

Confetti of flesh, bone

None of that weapons training would help him when the bullet hit him. Disoriented and grappling for consciousness, he willed his body to move. He dug his elbows into the grime-caked earth, clawing his way back to a nearby trench.

Suddenly, a menacing whir filled the air. A drone loomed above.

“I lunged for cover, but it was too late,” Prince recalled. With a chilling hiss, the drone unleashed a grenade. It landed on a Russian soldier near Prince. In a blinding flash and a deafening roar, an eruption of fire obliterated the Russian soldier. “Flesh and bone rained down on me like confetti.”

Amid a revolting smell of gunpowder and burned flesh, he had screamed.

“I thought I would also die,” he said, lowering his shirt on his left shoulder, revealing scars from the grenade explosion – some partially healed, others still raw, snaked across his torso. He gingerly rolls up a trouser leg to show his calf, with burns – some faded, others still a vivid reminder of the searing heat from the blast. “It was blood, blood, blood.”

Prince had shed his heavy jacket, a biscuit packet and medicines needed for survival, and crawled away. His vision blurry, he heard somebody calling out, “Prince, come quickly!”

“It was Vineet, my cousin, whom I hadn’t seen in a month. He had witnessed my fall after the grenade explosion,” Prince said.

“In a few minutes, I reached near the trench. Vineeth pulled me down into it. It was dark by then. I couldn’t see the blood drenching my uniform, but I could smell blood. And I was losing consciousness. I saw Vineeth injecting me with painkillers,” Prince remembered.

Prince and Vineeth decided to rest that night in the trench, which they knew led back to a Russian army base camp. As dawn arrived, they began to crawl once more.

“By the time I reached base camp, I was nearly dead. Vineeth had filled the commanders in on what happened. The last thing I remember was someone rushing in with a stretcher and carrying me away,” Prince recounted.

Ten days in hospital

On February 7, Prince woke to the sterile confines of a hospital room. Doctors, their faces etched with haunted concern, extracted a bullet lodged in his skull. A bullet he had carried, unknowingly, through his harrowing escape.

In all, he spent 10 days in five hospitals, starting in Luhansk and ending in Rostov. Finally, he was released and ordered to return to Luhansk for his commander’s signature on his injury leave request.

Prince, defying orders to remain at his camp in Luhansk, returned to Moscow. He fabricated a story about visiting relatives in Moscow for a day and, remarkably, secured permission. Prince sought refuge in a church, where he met with a priest and pleaded for help.

The church helped him contact the Indian embassy and his family back home in India.

Finally, Prince returned home on April 3. On the way to Kerala, he had to stop in New Delhi, where he was debriefed by Indian security officials, who, in recent weeks, have made arrests and conducted raids against recruiters accused of luring people to Russia on false pretexts.

But the pattern of vulnerable Indians finding themselves trapped in job scams overseas is not limited to Russia’s war in Ukraine, experts say.

‘Left in the lurch’

Rafeek Ravuther, executive director of the Kerala-based Centre for Indian Migrant Studies, said most Indian migrants are duped by agents who promise them permanent residency in Europe.

“Many are taken on a tourist visa and left in the lurch,” Ravuther said. Prince and his cousins had also travelled to Russia on tourist visas.

Yet, despite this crisis, Ravuther said, political parties aren’t referring to these overseas job scams at all in their election manifestos. India votes in the world’s largest election over seven phases starting April 19. Kerala votes in the second phase on April 26.

If the dreams of a future abroad are often little more than mirages, there’s also little to hope for at home for millions of young Indians like Prince.

“In our coastal villages, the fishermen’s families are reeling under poverty. So, just to get out of the struggle, they even dare to migrate to war-torn countries,” said Eugine H Pereira, vicar general at Trivandrum Latin Catholic Arch Diocese, under which most fisher villages near Thiruvananthapuram fall.

Recently, the India Employment Report 2024 released by the International Labour Organization (ILO) and the Institute of Human Development (IHD), revealed that India’s youth between the ages of 15 and 34 account for almost 83 percent of the country’s unemployed workforce.

Prince is now working with the Indian government to try and secure the release of Vineeth and Tinu, his cousins who are still believed to be in Ukraine, fighting for Russia. That, he said, is his most pressing concern.

Beyond that too, the future hangs uncertain. Prince needs to repay the loans he had taken out to pay the recruiter. Only when the lingering pain on the left side of his body subsides can he dream of returning to the life he once lived – the rhythmic call of the sea and the freedom of fishing.

His parents urge him to undergo a detailed medical checkup, but he doesn’t have money for it. The regular summons from intelligence agencies and local police, who are probing the case, further disrupt his fragile peace.

Yet, beyond the storm in his head lies the familiar embrace of his village and the love of his family.

This, he said, is a second life, a precious gift snatched from the very jaws of death. Despite the economic desperation back home, he has no immediate plans of leaving again: In his village, he finds solace and the strength to rebuild.