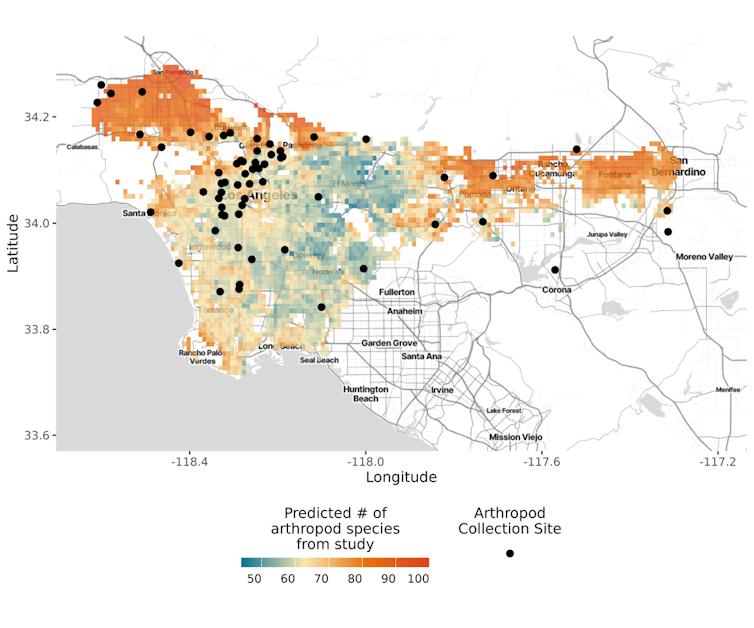

The most significant predictors of bug biodiversity in Los Angeles are proximity to the mountains and temperature stability throughout the year, according to a study we co-authored with Brian V. Brown of the Los Angeles Natural History Museum and colleagues at the University of Southern California and California State University.

The project used data from the museum’s BioSCAN project, where volunteers across Los Angeles allowed insect traps to be installed on their property between 2014 and 2018.

The analysis showed some surprising results. For instance, land values had little impact on the overall diversity of arthropods, specifically spiders and insects. This finding challenges the “luxury hypothesis,” the notion that wealthier neighborhoods, which tend to have more trees, always have greater biodiversity – an assumption that generally holds true for birds and mammals, including bats.

The BioSCAN study identified over 400 different species of bugs across Greater Los Angeles, many surviving despite pavement and habitat loss.

In fact, urban environments can be attractive to some invasive arthropod species. Often called urban opportunists, such species frequently come in waves that replace or restrict current species. For instance, about 20 years ago, Los Angeles’ native black widow spiders (Latrodectus hesperus) began to be replaced by brown widow spiders (Latrodectus geometricus). Recent evidence shows these interlopers are now being replaced by noble false widow spiders (Steatoda nobilis).

Why it matters

Bug populations are essential for people, who rely on them to provide pollination, decompose plant and animal material and control pest insects. These services are as important in cities as they are in rural environments – and are provided by insects for free.

Imagine a city where organic waste like dead animals or plant matter didn’t decompose. A city without insects would also mean an environment without birds and most other types of wildlife, many of which rely on insects for food. Such a place would also have no flowers, fruits or vegetables growing. In fact, a world without insects would be a world without humans.

Low arthropod diversity can lead to ecosystem imbalance. A 2022 study found that pests, like sap-feeding aphids, can get out of control in highly urban areas because there are not enough predators like beetles and spiders to keep them in check.

Most biodiversity studies are conducted in natural or even protected areas, but more and more, scientists are recognizing that urban areas can harbor many species. Understanding biodiversity in urban areas is important because cities are expected to continue spreading – with the United Nations predicting urban populations to grow by 2.5 billion by 2050.

What still isn’t known

Although we now know which factors most strongly influence arthropod diversity in Los Angeles, we don’t fully understand how this diversity translates to healthy urban ecosystems.

Scientists know more species lead to healthier urban ecosystems, but not all species contribute equally. For example, planting pollinator-friendly plants are a relatively easy intervention in urban environments, but it will not benefit all insect species.

What’s next

As part of the BioSCAN project, volunteers also allowed bioacoustic monitors to be installed on their properties, so future studies can include bats, which are also crucial for pollination and pest control in cities.

Additionally, researchers at the University of Southern California are continuing to study the same data set to understand seasonality in urban arthropod communities. In a warming climate, this knowledge could help predict future bug population shifts.

Overall, insights from these studies may help inform urban planning and development to support bug biodiversity, particularly as cities expand through urban sprawl.

Laura Melissa Guzman receives funding from Conservation, Food, and Health Foundation.

Charles Lehnen is receiving funding from external sources Iguanas in the Balance Grant and Gold Family Fellowship as well as internal USC funding sources USC Provost Fellowship, USC Graduate School Travel/Research Award, PhD Academy Scholarship & Research Fund, and USC Graduate Student Government GSG Professional Development Fund.

Teagan Baiotto does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.