At the start of 2001’s Bubble Boy, Jake Gyllenhaal wakes up to his first ever erection, screams in terror and hits it with a baseball bat. Trapped in a plastic bubble, he pines for the girl he spies through the window each day, who his mother has already christened “the whore next door”.

Unlike that year’s Donnie Darko, which was nearly given a straight-to-video release, this weirdly crude Disney comedy was meant to be Gyllenhaal’s star-making vehicle. It was, instead, an inexplicably controversial box office disaster. Nineteen years later, it feels like a forgotten instruction manual on how to survive coronavirus lockdown.

As we enter our fourth (or fifth, or 77th – it’s hard to keep track) week of self-quarantine, Bubble Boy is in many respects our collective present – all of us deprived of the outdoors, eager for the briefest of human interactions, and, if we don’t already live with our partners, with a case of the metaphorical tumbleweeds in our pants.

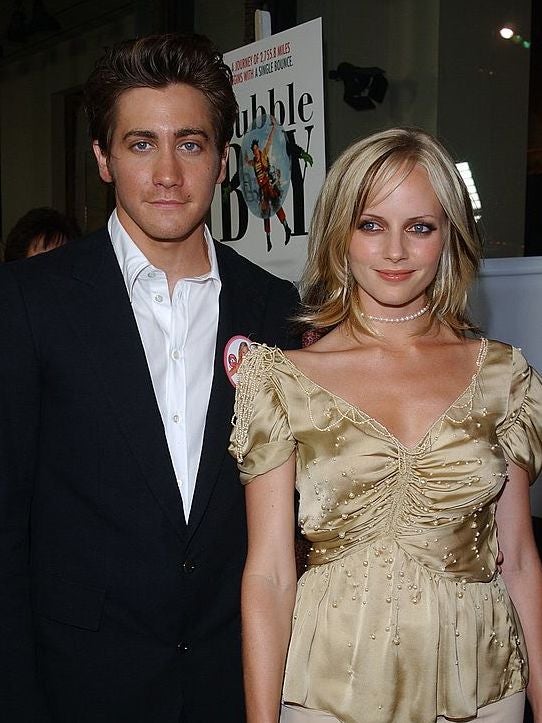

Gyllenhaal, in what was his second starring role in a movie, plays Jimmy, a hapless virgin with permanent hat hair and an auto-immune disorder from birth. Because of his condition, he’s always lived in a giant plastic bubble, his fundamentalist Christian parents raising him in isolation from the outside world. When he gets a visit from his fetching neighbour Chloe (Marley Shelton), however, Jimmy suddenly realises that he really, really wants to have sex. After Chloe gets engaged and leaves town, Jimmy manufactures a transportable bubble suit that allows him to roam the country in pursuit of his lost love.

What follows is a surreal road movie-cum-Wile E Coyote-style odyssey, with Jimmy encountering a doomsday cult, a travelling freak show run by the late Verne Troyer, and a weeping Hindu man convinced he has affronted God by accidentally running over a cow. It is the strangest and most inappropriate family comedy of the 21st century. That it’s about a horny teenager perpetually wrapped in plastic is arguably the least surreal part of it.

Boys in plastic bubbles have, for decades, occupied an unusual space in the American cultural landscape. In 1973, the United States became enraptured by the plight of David Vetter, or “David the Bubble Boy”, a young boy born with a severe combined immunodeficiency known as SCID that meant he had to live inside a sterile plastic chamber. His trauma brought to mass public attention what was previously a little-known disease. It even inspired an infamous 1976 TV movie, with his fictional avatar played by the far older and more tragically handsome John Travolta.

When Vetter died in 1984 at the age of 12, from complications following a bone marrow transplant, the country was plunged into mourning. But the odd, somewhat overblown hysteria over the case meant so-called “bubble boys” would quickly become targets of dark mockery. In 1992, an episode of Seinfeld saw a man’s plastic bubble home being accidentally deflated after a Trivial Pursuit squabble. A decade later, Bart Simpson would be placed in a plastic bubble for a week after being infected with something called “Panda virus”.

A comedy movie revolving around SCID, and featuring a boy in a bubble being run over by a bus and tackled to the ground by scantily clad mud wrestlers, understandably provoked some ire. But Disney, which distributed Bubble Boy through its Touchstone Pictures company, had no idea that many would call for a total boycott of the film.

“Did they even think about how this might affect those who have to deal with this life-threatening disease?” asked Carol Ann Demaret, mother of David Vetter, in the Washington Post.

“I’m offended by the fact that it was treated with such disregard to his memory,” she told BBC News. “It says to our young adolescents, and that is their target audience, that it’s okay to laugh at those with special needs or a handicap … It treats the disease, a primary immune disease, with little regard by mocking it.” Another mother of a young boy with SCID said: “All of our children are known as bubble boys. What are they going to have to face at school after this comes out?”

It’s impossible to say whether audiences in 2001, the few that showed up, were laughing at Gyllenhaal’s character or with him. Jimmy gets off lightly, at least, in comparison with other minority groups – a bizarre scene in which Jimmy’s mother plots to blame her son’s disappearance on a Jewish ransom scheme (“It’s the Jews, Morton, they’re gonna want more than $100,000!”) is a particular nadir.

But in 2020, as we all sit in bubbles of our own making, shaken by an invisible enemy, Bubble Boy seems genuinely empathetic – even moving. It’s suddenly easy to identify with Jimmy finding solace in episodes of old TV shows, and his eager pining for human contact. He’s an ace on the electric guitar, a skill only developed out of self-isolating necessity, and wishes he could go to the movies.

If anything, Bubble Boy also brings to mind how ignorant many of us are to those for whom quarantine isn’t a government-enforced scenario. Self-isolation is boring, physically depleting and enormously depressing, but will also (and surely this isn’t too naive?) eventually end. For the “bubble boys” of the world – and those with bad immune systems, chronic illnesses or agoraphobia – self-isolation is an everyday part of existence.

Gyllenhaal hasn’t spoken much of Bubble Boy, which has always had the reputation of being the rotten, decaying portrait in the attic when it comes to his two star-making roles in 2001. But Gyllenhaal is also the most consistently likeable yet entirely un-fun actor of his generation, so it’s no real surprise. Bubble Boy would have also been long forgotten if not for his involvement – it opened at number 13 at the US box office in August 2001, and became one of the biggest flops of the year. Gyllenhaal, otherwise ascending the Hollywood ladder, was likely glad to see the back of it.

“It was a different script [originally],” Gyllenhaal told Elle magazine in 2015, during a rare moment of levity on the press tour for his weepy drama Demolition. “The director, Blair Hayes, is a really beautiful, creative, open, loving artist, and that was a case of a studio coming in and telling him he had to make a movie a particular way, and he lost his vision. His initial vision was pretty much equal to Donnie Darko in its oddity.”

Whatever the creative disappointments that occurred on set, you do wish that Gyllenhaal would be a little more proud of it today. It’s no Brokeback Mountain, of course, nor is it on a par with a Zodiac or a Donnie. Compared to something like Prince of Persia, though, it’s an eerily perceptive and oddly heartwarming weirdo treat. And a sort-of glimpse at a future few of us ever expected to become the temporary norm.