The story of Brooke Shields is often told in terms of her age. She was 11 months old when she shot her first ad campaign for Ivory soap. She was 11 years old when she played a child prostitute in Louis Malle’s 1978 film Pretty Baby and 14 years old when she starred with an 18-year-old Christopher Atkins as shipwrecked cousins discovering their sexuality in The Blue Lagoon. She was 15 years old when she appeared as a teen in lust in the Franco Zeffirelli film Endless Love. She was also 15 when she appeared in her first Calvin Klein ad, uttering these words to camera: “You want to know what comes in between me and my Calvins? Nothing.”

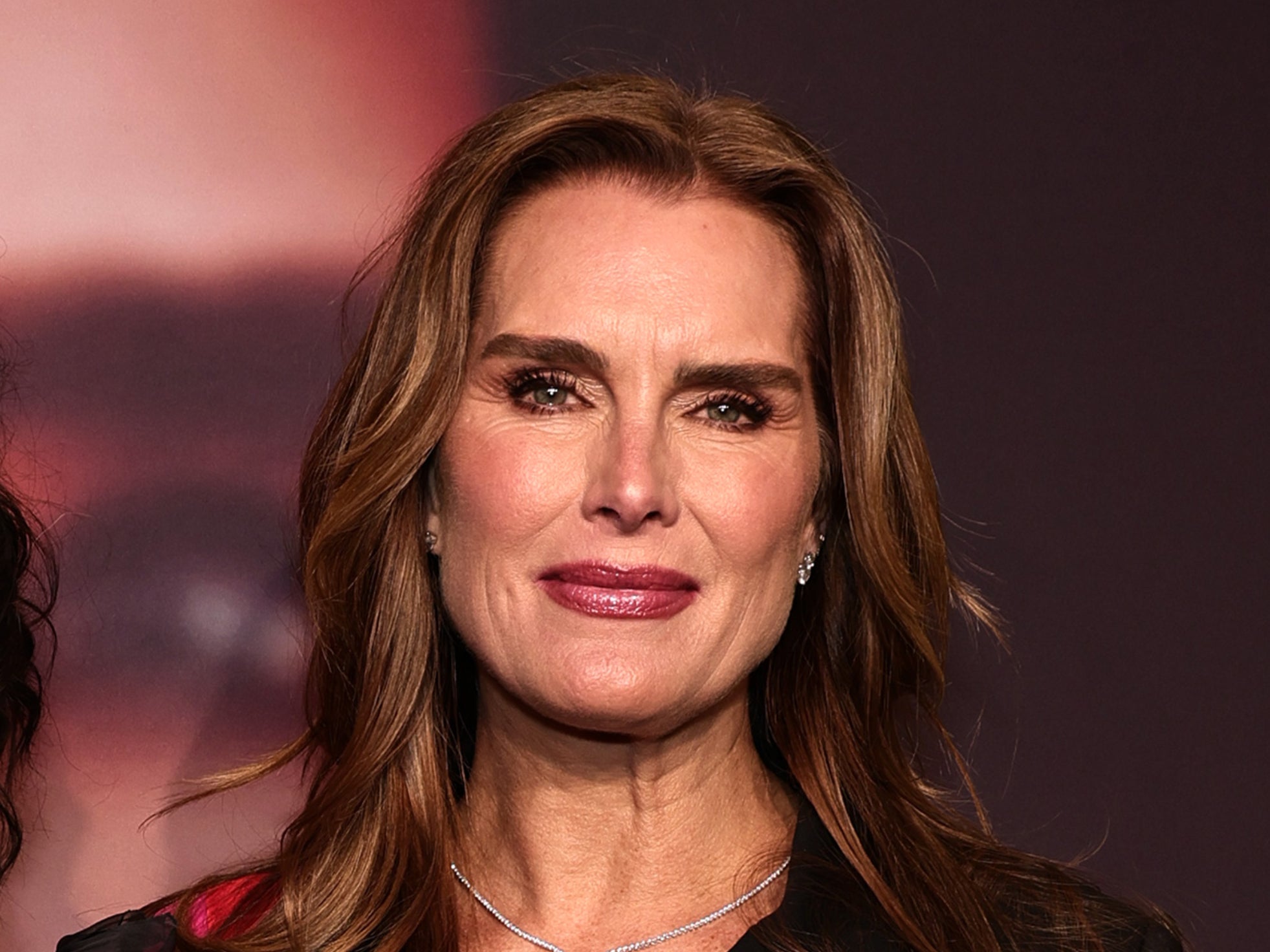

To present her story this way is to highlight just how young Shields was when all these milestones were happening, how young she was when she became a paragon of all American beauty. For many, Shields, now 59, will be indelibly associated with her teenage dimpled, bushy-browed ingenue self, frozen in time like a butterfly in epoxy. Her new book, then, is aptly titled: Brooke Shields Is Not Allowed to Get Old: Thoughts on Ageing as a Woman.

Brooke Shields Is Not Allowed to Get Old is part of a current trend of books and films to examine the subject of women aging. Last week, The Substance– a body-horror film about an aging, fading star played by Demi Moore – was nominated for five Golden Globes. Next month, Naomi Watts will publish a memoir about her experience of menopause knowingly titled Dare I Say It: Everything I Wish I Knew About Menopause.

There is no universal experience of aging. And certainly, the lived experience of a very famous, very rich celebrity everyone agrees is drop-dead gorgeous is not the default. On paper, Shields doesn’t have much in common with the average woman who might pick up this book. But in other ways, she is the perfect person for this job, someone whose value has been tied up with her youth since she first waddled on camera, the bouncing baby of Ivory soap: “For young looking skin like this…”

Shields shares these thoughts across 14 light-hearted conversational chapters. “What the actual f***?” is a frequent refrain from the actor and model, who prefers the BFF-style second-person: her earlier memoirs There Was a Little Girl and Down Came The Rain and – about the death of her mother and postpartum depression – had the same tone. But unlike those subjects, she writes, aging isn’t something to endure or survive. It’s something to embrace.

So what do we learn about Shields? Quite a bit about her medical history, for one thing. In one of the more illuminating chapters that reaches beyond the platitudes that plague the book, Shields speaks about learning medical self-advocacy. After an abnormal pap smear in her mid-thirties, Shields underwent a cone biopsy of her cervix. “No one had bothered to tell me, for example, that I’d been packed with gauze to stop the bleeding,” she writes. “When that gauze suddenly fell out… Well, I’m not exaggerating when I tell you I thought I was hemorrhaging and dying, or else giving birth to something I didn’t even know I was carrying. I felt like my entire uterus had fallen out onto the bathroom floor.”

Not only that, but no one had told her that the biopsy could make it difficult to conceive – something Shields learnt only years later when she was trying to get pregnant. In the end, she underwent seven cycles of IVF before giving birth to her first daughter – a fact she caveats with one of the book’s perfunctory acknowledgements of her own privilege. Elsewhere, she recalls having to fight for a second X-Ray after a femur surgery resulted in excruciating pain that the doctors insisted was normal post-op discomfort. Turns out the surgeon had made a mistake.

In one particularly shocking moment, another doctor, she writes, took it upon himself to “gift” Shields an “unsolicited vaginal rejuvenation” that left her uncomfortable and in pain for months afterwards (“I tightened you up!” he tells her giddily, expecting gratitude.) “It was not something I wanted. I felt numb. I got dressed, went to my car, and drove home in a stupor,” she wrote, later adding: “This man surgically altered my body without my consent. And he thought he had done me a favor by throwing in a ‘bonus procedure.’”

It’s perhaps the only quote-unquote bombshell in a memoir that mostly trades in generalities. Throughout the book, Shields rehashes anecdotes from her life (big and small) through the lens of hard-earned, time-earned sagacity, re-evaluating certain scenarios and casting them in a new light. “If that had happened now, I’d be less forgiving,” she writes.

Brooke Shields is not allowed to get old is overwhelmingly positive in a way that can read like a parenting manual. Stand your ground; speak up for yourself; embrace your flaws; discover the power in knowing your limits – listen to Brooke! It is a 234-page fount of unapologetic optimism – which can be tiring. The chapter chronicling her string of health scares sees Shields reckoning with her mortality. It ends with her triumphant realisation that life really is as precious as everyone says it is. “I learned that our time is short. That it’s healthier, and so much more fun, to celebrate what you do have rather than what you don’t. That every day is actually a gift. All those clichés? Turns out they’re true!”

A lot of what Shields talks about is nothing new, and yet there is still value in a book like this being published – the same way there is value in Demi Moore speaking out about ageism in Hollywood, and Naomi Watts getting candid about menopause. Evidently, we are moving into a new era of celebrity memoir: more self-help manuals, less ghost-written hagiographies. A cynic might call memoirs like Shields’ narcissistic navel-gazing, and certainly, admission itself is not always of value, nor is it always useful to others – but I’d argue there is more to be said here.

Shields said she wrote the book so that other women would feel less alone. In 1972, Simone De Beauvoir had much the same aspirations. The feminist philosopher published her book The Coming of Age to “break the conspiracy of silence” that 50 years later has still got a grip on us.

Surprisingly, only one chapter (“More Than a Pretty Face”) deals explicitly with the physical effects of aging. She writes about the flesh around her thighs, which look “as if Silly Putty had melted into a frown around my kneecaps”. Earlier in the book, she recalls the stark realisation that the onlookers in New York City weren’t looking at her but her daughters – “the two beauties by my side”.

The question of how beauty and youth are inextricably linked for women hovers over Shields’ book but is not explored to any satisfying extent. Instead, Shields takes the perspective of a woman who has come out the other end with “an appreciation for all the nuances and idiosyncrasies, inside and out, that make you you”. But she leaves no comprehensive guide on how to get there beyond a cursory assurance that: don’t worry, it’ll come.

I don’t regret doing those jobs, because they paid the bills and afforded me the life I lived, but I can look back and see that I helped perpetuate certain myths about how women should look

To her credit Shields recognises her part in perpetuating some of these impossible ideals. “I can’t deny that I played a role in contributing to those standards,” Shields writes of a modelling career that saw her zipped into “skintight Calvins” and gracing the cover of Life wearing an “itty-bitty” red bikini more than once. “I don’t regret doing those jobs, because they paid the bills and afforded me the life I lived, but I can look back and see that I helped perpetuate certain myths about how women should look.” She confesses to still buying into those myths today, admitting to taping her thighs for the illusion of slimmer legs.

Earlier in the book, she invokes Marilyn Monroe to illustrate her point about beauty. “I remember seeing a picture of what Marilyn Monroe would look like if she were still alive today, and it was truly impossible to wrap my head around,” she wrote. “But she died looking like Marilyn Monroe. For me, as my body and face change in all the ways they should [...] there is this sense of How dare you? That was never the plan, young lady! And, to be totally honeest, there have been times when it’s made me feel like a disappointment.”

But there are silver linings to getting older, Shields continues to insist. She doubts, for example, that she would have had the guts to publicly call out Tom Cruise over his on-air remarks about her use of antidepressants had the incident not occurred almost exactly one month after her 40th birthday. Shields offers studies and statistics about why aging is a good thing. Laura Cartensen, a professor of psychology and founding director of the Stanford Center on Longevity, found that people over 50 report more positive emotions and fewer negative ones – and the negative ones they do report are less intense. Translation: older people tend to be happier. Or at least, as Shields writes, tend to feel a “richer sort of happiness” enhanced by years of experiences both good and bad.

It is easy to get swept up in Shields’ positive prose. Her promises of wisdom and self-love in older age are enticing, glimmering like the light at the end of a long tunnel. But positive thinking can only take us so far – Shields says so herself in the introduction to her book. “I was firing on all cylinders,” she writes of entering her forties. “Plus, I’d arrived at a place of self-acceptance [...] And yet, as my forties progressed into my fifties, I began to notice that external perceptions didn’t seem to match up with my internal sense of self.” For example, she says, “My industry no longer received me with the same enthusiasm I had come to expect.” We might think ourselves beautiful and worthy in old age, but if our society does not agree, surely we still suffer the ramifications.

We cannot “positive-think” ourselves out of a society marred by misogyny and ageism. That takes work outside of ourselves, to change our systems and institutions. What Shields is talking about is, well, I suppose it’a a good start.

‘Brooke Shields Is Not Allowed to Get Old’ is published on 14 January by Little Brown