One morning, Pico Iyer stepped out of the flat he shares with his Japanese wife in suburban Japan and instantly felt transported to the Himalayas.

“A sudden mist enshrouds our little lane and there’s a mountain enclosedness to everything, though in Nepal the trash would never be confined to a single compact square on the street corner,” writes the celebrated author in his latest book, Autumn Light: Season of Fire and Farewells. A woman, he adds, is “padding past in her jammies … I suppress a smile, until I remember I’m in jammies, too.”

Readers unfamiliar with Iyer’s writing would be forgiven for asking why any of this, with the possible exception of Japan’s and Nepal’s contrasting garbage disposal methods, is interesting. Others, however, will not bother suppressing smiles of their own as they anticipate Iyer’s next cross-cultural surprise: “At the bus stop across the street, a young woman appears to be sleeping where she stands, one of those Japanese tricks the likes of me will never fathom.”

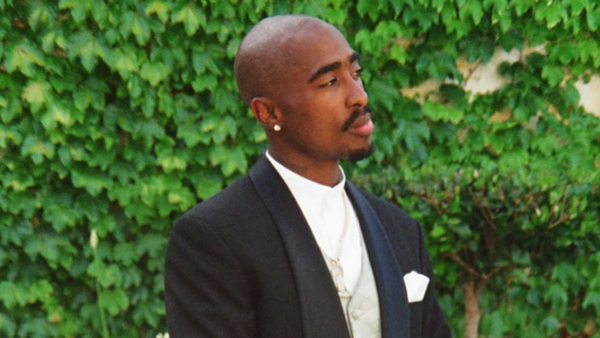

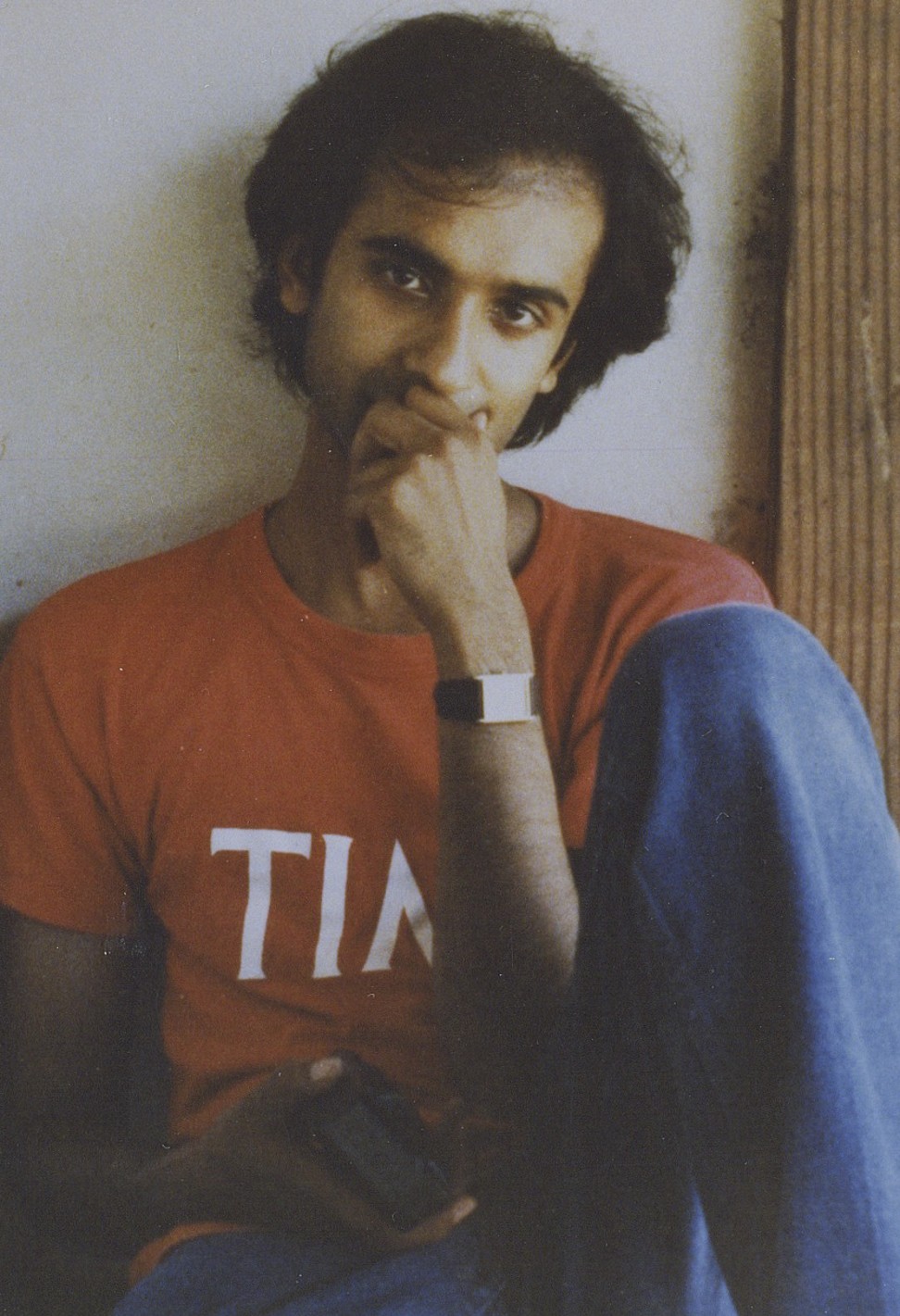

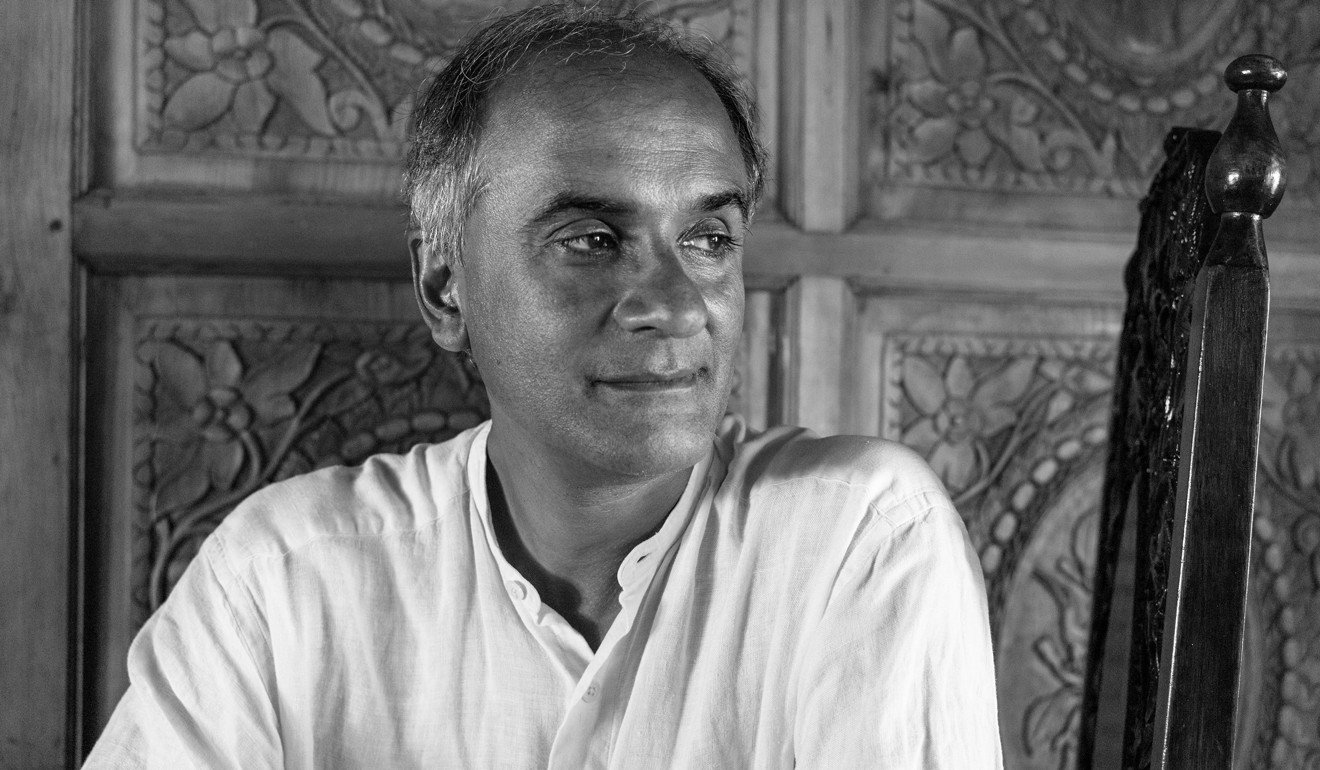

Born in England to Indian parents who migrated to California when he was seven years old, Iyer is a sharp-eyed observer of cultural collisions and cross-pollinations, a modern-day Mark Twain capable of leaping across borders by highlighting a single conundrum, irony or ambiguity.

In Autumn Light, he presents to the outside world with simplicity, grandeur and sensitivity an idyllic, upscale neighbourhood in Nara, Japan’s ancient capital. Called Deer’s Slope, the place is inhabited mostly by retirees, many of them a full decade past 70, but agile enough to beat teenagers at ping-pong.

His portrait of suburban life, he says, is “relatively unmediated, so we can see how close Japan can be to the rest of us, on a human level”.

Indeed, a refrain of Tolstoy’s runs throughout the book’s long, rich sentences, scalloped cadences and galloping drive: “Look carefully at your village and you’ll be universal.”

A prolific author regularly featured on TED Talks, Iyer shot to literary prominence in 1988 with Video Night in Kathmandu and Other Reports From the Not-So-Far East, his debut work that foresaw the post-cold-war convergence of East and West. He has written a dozen books since then, and his 14th, titled A Beginner’s Guide to Japan, is scheduled for publication in September. It’s “the exact opposite” of Autumn Light, says Iyer, “more like an outsider talking back to Japan and focusing on everything about it that’s different and startling”.

Much of Iyer’s non-fiction is inspired by the sense of foreignness he carries with him wherever he goes. He was among the first writers to put his finger on the perils and promises of a rapidly globalising world in which an international lifestyle often tends to be both enriching and alienating.

When people such as him embrace multiple identities, Iyer points out, they are rendered neither expatriates nor nomads, exiles nor refugees, but something in between.

“The country where people look like me [India] is the one where I can’t speak the language,” Iyer wrote in The Global Soul: Jet Lag, Shopping Malls, and the Search for Home, his sixth book, published in 2000. “The country where people sound like me [Britain] is a place where I look highly alien, and the country where people live like me [America] is the most foreign space of all.”

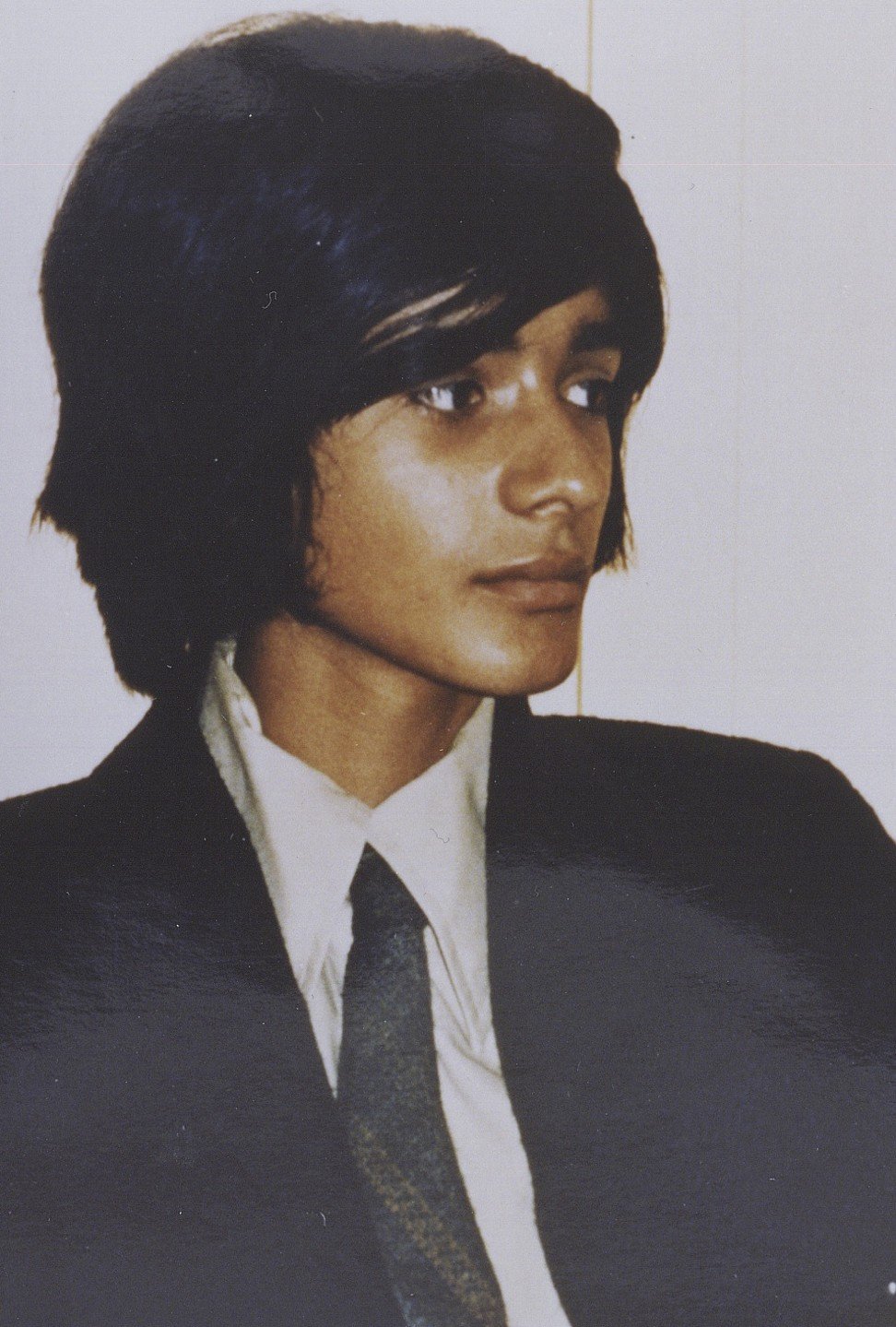

The only child of Hindu-born theosophists, Iyer was educated at Eton, Oxford and Harvard. Except for his parents, who named him after Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, the renowned Italian Renaissance humanist, Iyer never saw any Indians while growing up – and he learned not a single word of any of their native tongues.

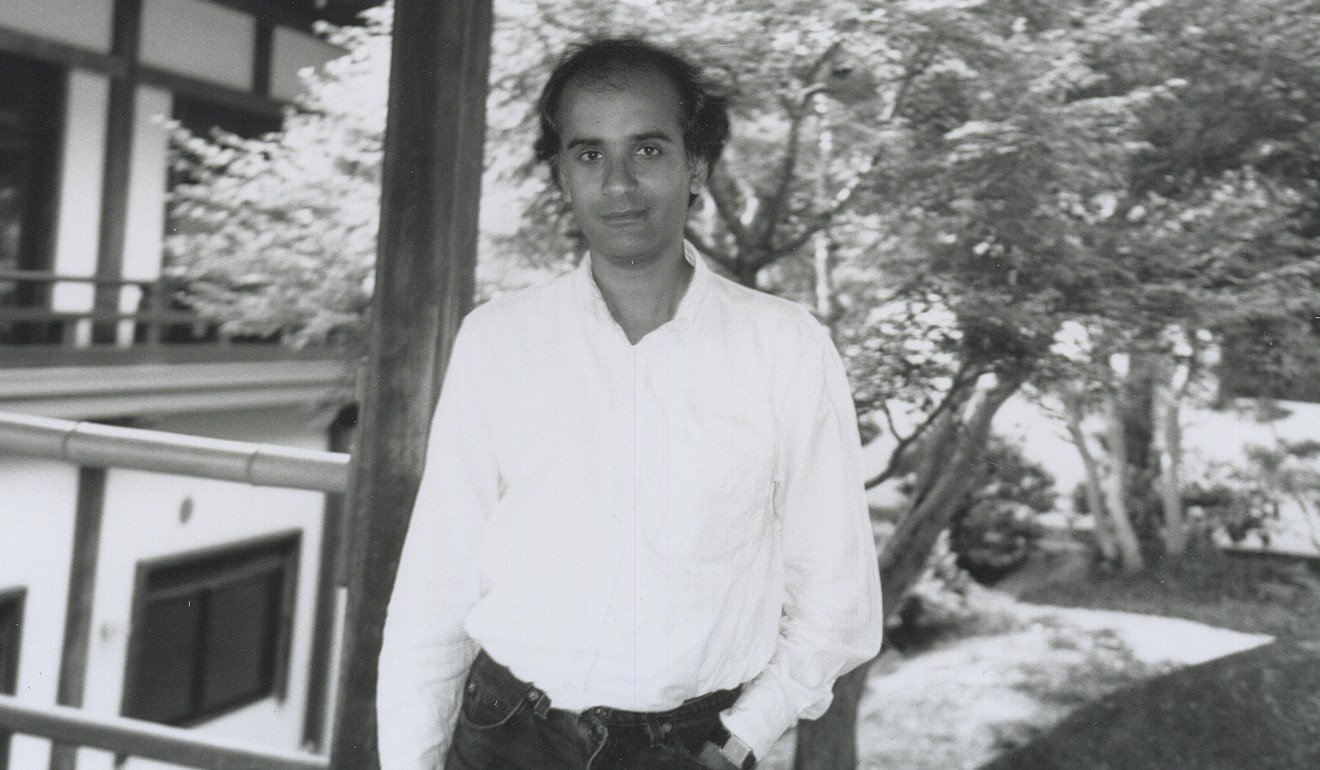

Iyer fell in love with Japan when he was 26 years old and at the peak of his career as a journalist writing about global affairs for Time magazine. In the autumn of 1983, he was returning to New York City from a business trip to Hong Kong when his Japan Airlines itinerary called for an overnight layover at Narita Airport.

“It was the last thing I wanted,” Iyer recalls in Autumn Light. “Narita was infamous for 11 years of violent protests by local farmers over the demolition of their rice paddies, culminating in a burning truck sent through the new airport gates not many years before.”

The next morning, with four hours still to kill before his check-in, Iyer took a shuttle into the city. He expected to be fully bored, but when the bus stopped at a tranquil Buddhist temple, Iyer suddenly felt as though he had been there in a past life. By the time he boarded his plane, Iyer decided to leave his cushy job in Manhattan and return to Japan.

He arrived four autumns later, suitcase in hand, and knocked on the door of a monastery in the backstreets of Kyoto.

“My boyish plan was to spend a year in a bare room, learning about everything I couldn’t see in Midtown Manhattan,” Iyer writes, adding: “The plan lasted precisely a week, which was long enough for me to realise that scrubbing floors and raking leaves before joining two monks crashed out in front of the TV was not quite what my romantic notions had conceived.”

At a Zen centre in Kyoto one day, Iyer ran into Hiroko, a charming young mother of two who invited him to her daughter’s fifth birthday a few days later. Before he knew it, writes Iyer, “my year of exploring temple life became a year of watching a new love take flight”.

Falling in love is easy, but staying in love is often the real-world challenge many of us face – and brings its own enduring beauties – British writer Pico Iyer

Hiroko went on to divorce her husband; in response, her elder brother, a Jungian analyst, cut off all ties with the entire family. In 1992, Hiroko and Iyer moved to Nara, where they have lived ever since in the same US$700-a-month, two-bedroom flat.

It wasn’t until 1999, however, that they got married. “I felt her children might suffer enough having a funny-looking foreigner in the house,” explains Iyer. “But to have an Indian stepfather might be even worse while they were in school, so we didn’t hurry towards the altar.”

Iyer spends an average of seven months a year in Japan – on a tourist visa, because he wants as little as possible to do with the country’s official side. He devotes the rest of his time to travelling for his work, meditating in a Catholic monastery in California, and looking after his 87-year-old mother who lives nearby.

Even though Iyer barely speaks any Japanese, and Hiroko speaks very rudimentary English, the couple have no trouble communicating. In fact, within a year of meeting Hiroko, Iyer felt he knew her well enough to write a whole novel based on her. Titled The Lady and the Monk: Four Seasons in Kyoto, the 1991 story is a sort of prequel to Autumn Light. On his recent book tours, many of Iyer’s fans asked him about the relationship between the two books.

“I tell them that autumn has blessings spring cannot imagine, in part because it has the memory of spring within it,” Iyer says poetically, adding: “Falling in love is easy, but staying in love is often the real-world challenge many of us face – and brings its own enduring beauties.”

Parts of Autumn Light are devoted to the themes of ageing and children leaving home. Much of the narrative surrounds the death of Iyer’s father-in-law and the collapse of his mother-in-law into dementia.

But the contemplations on loss are set against the background of a daily routine that involves living with the cycles of the seasons and learning to accept the permanence of change.

“Cherry blossoms, pretty and frothy as schoolgirls’ giggles, are the face the country likes to present the world, all pink and white eroticism,” writes Iyer. “But it’s the reddening of the maple leaves under a blaze of ceramic-blue skies that is the place’s secret heart.”

Steeped in the Buddhist idea of impermanence, Japan has always known to cherish things “precisely because they cannot last; it’s their frailty that adds sweetness to their beauty”, Iyer reminds us. “Autumn poses the question we all have to live with: how to hold on to the things we love even though we know that we and they are dying.”

Although ostensibly about mortality and grief, at its core Autumn Light is a celebration of enigmas. Based on some 8,000 pages of notes collected over 16 years, it is a distillation of everything Iyer knows about Japan – a testament to his 32-year aspiration to embrace “the domestic spheres of Japan, rich in surprises and secrets”.